Zhan Wang was demonstrating his installtion

By Liu Libin

Part I?? From Obsession with A Mode of Existence to Alienation of Reality

Memories of his maternal grandfather from the age 2 to 4 act as a turning point for Zhan Wang’s life, which will be mentioned several times in his retrospective passages highlighted in this article. There are three points worth noting of this experience: the first one is that he is, different from other intellectuals around him though such a mode of existence has existed in China for thousands of years. However, due to modernization during the 19th and 20th century, especially the revolutionary baptism of the founding of People’s Republic of China, such a mode of existence more or less vanished. The second one is a special visual memory, such as the traditional Chinese table of eight persons, long narrow tables, vase with a plum pattern on it (1)…All these attentive objects and designs unsealed the ‘visionary’ pattern of Zhan’s early life. His eyes captured, a indulged in what he saw, but also learned to focus (or ‘gaze’). The third thing is, his grandfather as a ‘painter to be’ did Chinese traditional painting every day. His behavior and interests became a lingering influence to Zhan in days to come. Zhan deemed him as a ‘fellow traveler’. The unspoken pact could only be realized by the twinning of these 2 people, and such a pact was beyond the expression provided by Zhan’s young heart, a comfort and a warmth that continues to today.

We are all ‘living’. It’s a basic fact. In fact Yu Hua’s(2) novel To Live(3) put the existence of a man on this level: on one aspect, endowing a particular quality to ‘death’ and ‘existence’; on the other aspect revealed resignation and the chill of ‘existence’ in change times. It specified ‘how to live’ as the social character of an individual; and most people continue their ‘existence’ on this level. The Chinese idiom ‘work on livelihood’ and ‘bustle in and out’ implies the meaning of such existence. ‘What to live for?’ is the reason for people’s existence, it decides special qualities and transcendence (rather than the actual) mode of existence.

In the present context, the third implication of mode of existence ‘what to live for’ is usually connected with the objective and ideal: in some sense, it could be the pursuit of fame and interest; speaking from a more intense point of view, even ideals are too often simplified or even idolized. Such a value of existence that is simplified and oriented by ‘objective’ formed the root of people’s misery. The fundamental problem is, it encourages people to focus on the ‘result’ rather than the ‘process’. However the existence of man is actually a process. I think the meaning of Zhan’s grandfather’s existence is that life is more than just about realizing some objective value, the process of life itself is the value. One should offer an introspective on himself rather than gazing at the starry night and practically realizing the ‘meaning’ he realizes into his daily meals and activities. In the value judgments at the early stage of People’s Republic of China, or in Zhan’s childhood, such an ordinary life were usually deemed as ‘mediocre’ while ‘revolution’, ‘fighting’, ‘sacrifice’ and ‘ideal’ were glorified.

A different from his grandfather’s home, is the visual memory as there’s nothing to be viewed at Zhan’s own home. The most visually influential thing is ‘Portrait of the Leader’(1) . Accordingly, his parents were busy with their revolutionary work, which sharply contradicts with his grandfather’s life.

Man needs a spiritual homeland and it’s often materialized and temporary. For an outsider, the homeland is a world they can never really enter. However for the owner of the homeland, it’s the reality of him at the time and reliance on imagination that comes later on. As with Zhan, during his childhood, Leonardo da Vinci’s had an uncle ‘not engaged in proper duties’. While the view of his brother (Da Vinci’s father) who was a public notary and focused on reality, the uncle was basically a debauchee and disgrace to the family. But in Da Vinci’s view, the uncle is doubtlessly a gift from heaven. Every day the uncle took Da Vinci to stroll aimlessly in the fields, catching bugs and looking at flowers, touching animals and studying animal bodies. It is the two or three years of an aimless life when Da Vinci opened his eyes and formed his way of thinking through research and analysis of the world. Later when Da Vinci went to Florence, his tutor found with surprise that the student needed no education because he had his own way of studying this world. He could obtain knowledge beyond the tutor’s imagination through each detail, therefore Da Vinci dropped out and his father then sent him to a mill at Verrocchio. As with Da Vinci, Zhan was lucky. Though the grandfather was a traditional intellectual, the uncle allowed him to have fun so they enjoyed different childhoods.

Lingering with the notion of a mode of existence as it can offer an approval with a value of value. In a deeper sense, such an experience and memories resulted in alienation or a warning of reality, or doubt, or we could say ‘a(chǎn)nimosity’. Recently, Bei Dao(4) gave a speech at Hong Kong Book Fair where he mentioned that “A writer should keep tense animosity with his time. He should be far away from the mainstream, and be critical to all utterances. Some writers claimed he’s only responsible for his words. It’s nonsense. You must keep a complicated viewpoint and a response in writing. Such an ancient animosity does not only linger in the political sense. Every writer should have a long term view and a broader idea so as to have a profound observation of society and the economy.”

Zhan mentioned in his Summary of Creation that “I had no hobbies other than art. If I had any I’d like to consider the imagination of the law of things and day-dreams. I also like harmless tricks and plotting, but it’s purely conceptual hobbies and a spirit of mischief.” What’s the relationship between the origin of the ‘day-dream’ and his childhood? Why does he always linger between reality and surrealism? What is the state of “the spirit of mischief”? Did his different lifestyle during his childhood make his alienation of ‘home of my own in reality’ a doubt and animosity for the society he lives in?

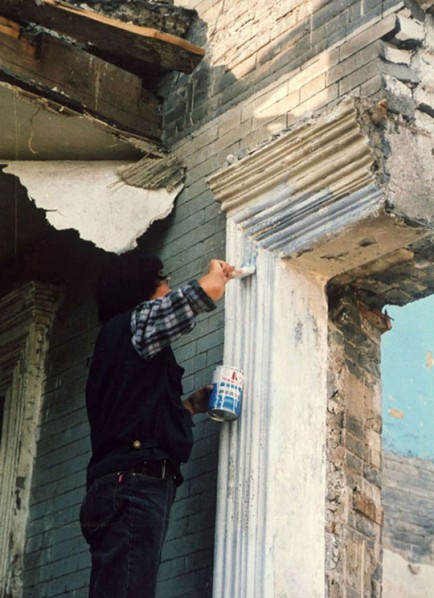

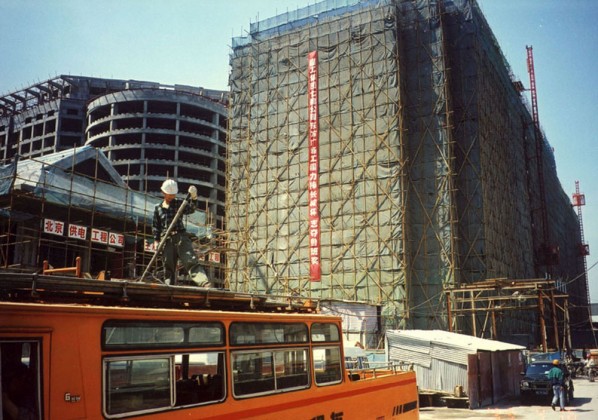

In 1994, Zhan was distressed due to his memories of existence in the process of such a large scale urbanization in China. He created a performance art “94 Clean Ruins” at a symbolic location Wangfujing Street of China’s economic center in Beijing. On November 12th, he spent a whole day in a small and simple traditional Chinese building that was to be demolished east Wangfujing Street, he redecorated and washed the old house that had been half demolished. He washed a pillar in the ruin with red bricklayer and painted the bricklayer with red paint again. He washed and painted half of white door frame that had survived with white paint. He cleaned some ceramic tiles with a cloth, painted the wall with interior coatings. At dawn on the same day, bulldozers started to work, continued demolishing the remains of the building. Several days later, the place was leveled to the ground.

01 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

02 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

03 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

04 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

05 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

06 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

07 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

08 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

09 Clean Ruins, 1994; photography, 60x80

When he talked about this creation, Wu Hung said “Internalizing such temporariness and unsteadiness with personal involvement of the artist, Zhan designed the performance art he called ‘Clean Ruins’. Here his work became the object for demolition: he chose a half demolished building to fix, wash thoroughly, paint windowsills, and fill up cracks with mortar. But before he could complete his work the building had already been pushed down by a bulldozer.” Zhan’s work contains a strong sense of alienation and illusion, not only an illusion of the urban city, but also of his creation. At the beginning it’s resignation, then possibly grief and indignation, or a combination of both. In the words of Zhan’s “Urban Dreams” he expresses his illusion well “Everything is hypothetical, everything is imaginative, everything is fake; Shattered in the daytime, rebuilt in the night, recuperated to build up energy in a circle for days and years, recurrent in life and death, never waking up. This is the biggest inspiration I have from urban life today. This is the dream of the ‘Modern City’!... Urban life is an illusion and hypothesis. For example, the beautiful, luxurious and fantastic city you see at night are still reinforcements with bricks as well as glass walls, how disappointing; just like in a crowded dancing hall lights suddenly come on and the true face of those coquettish women are revealed!”

To be continued …