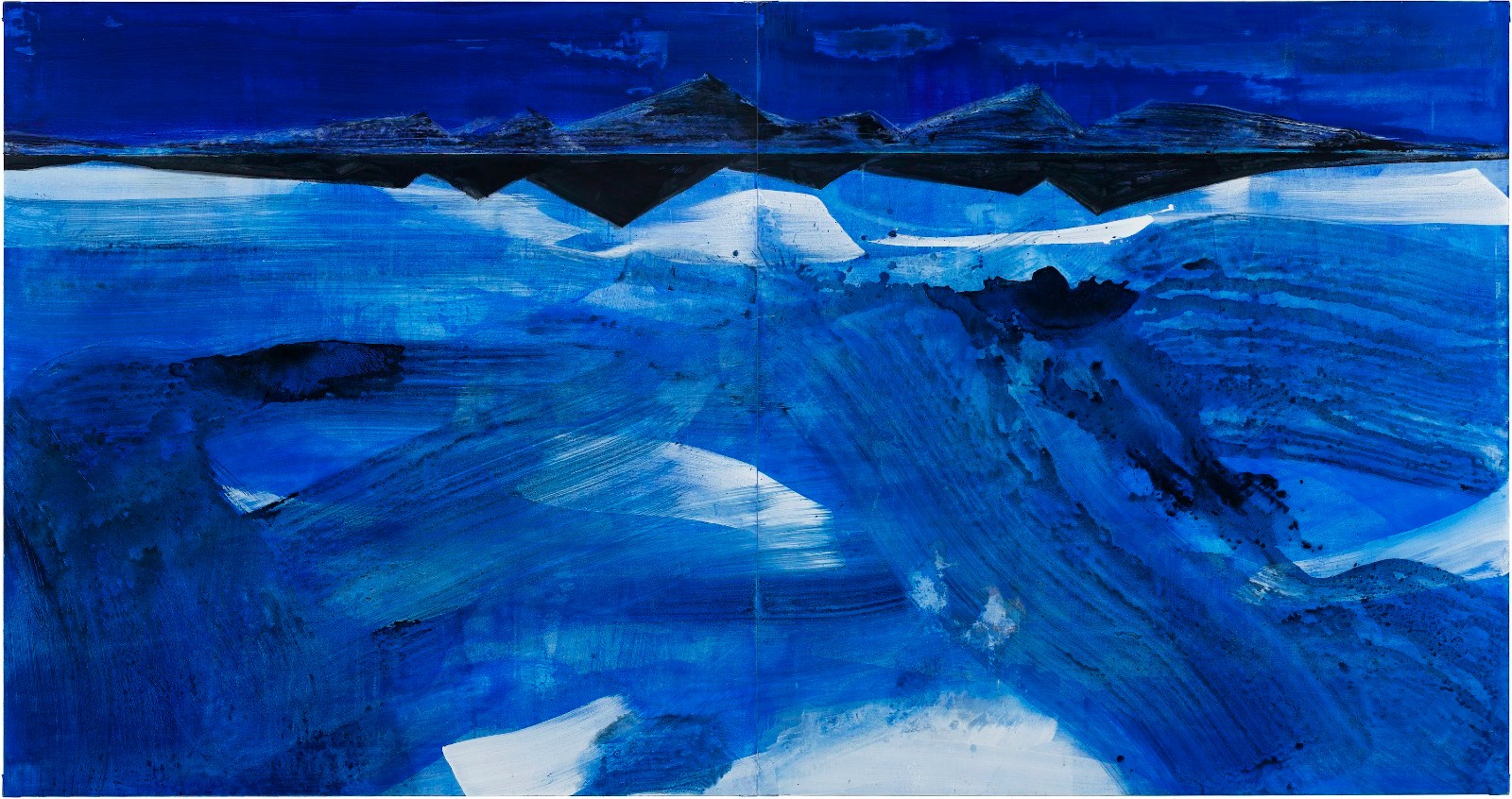

In 2010, Liu Shangying lived in a yurt with Buryat herdsmen on the Hulun Buir Grassland while he had travelled all over the eastern and northeastern parts of Inner Mongolia. One night, when the herdsmen came back from herding and they found that a mother sheep and lamb had been lost. He went out with the herdsmen to look for them. This experience was juxtaposed with both the ancient and mysterious atmosphere in his eyes, which had left a deep impression on him. After he returned to Beijing, Liu Shangying created the symbolic work “Sheep Chase” based on his experience. The 5.7-meter-wide and 2-meter-high painting was the first large-scale painting in his oeuvre.

Sheep Chase, Oil on canvas, 200×570cm, 2010

Twelve years later, Liu Shangying’s solo exhibition entitled “Walking Between Worlds” was held at the TAG Art Museum, which collectively displayed 5 of his creative projects that recorded his experiences walking within nature for over a decade. This “Sheep Chase” with a realistic style was placed as the first work for the exhibition. Together with a large number of large-scale abstract works, it seems to be distracted. Through sorting out the clues of his creations, this can be regarded as the “beginning” when Liu Shangying embarked on his journey to search, work and paint in nature. It made Liu Shangying think for the first time: Why can’t he stop running away from cities? What was he looking for when he left Beijing and visited the grassland?

In the second year after that, Liu Shangying embarked on a longer journey. Since 2011, he has continued to visit Ngari in Tibet, Ejina in Inner Mongolia, Lop Nur in Xinjiang, Altun Mountains, Tian Shan (also known as the Tengri Tagh) and other places to carry out his creations in the field. He has completed four solo shows of natural explorations including at the Red City Ruins of Ejina, Inner Mongolia, in 2017; at the Toksun Red River Valley in Xinjiang in 2019; at Shaziquan, Altun Mountains and Qimantag Mountains in 2021; in the River Valley of Tian Shan and the top of the mountain in 2022. He had more thrilling experiences each time, and his creative methods tended to be more uncertain or even “bizarre,” but his mind became more and more determined and satisfied.

Exhibition View of Walking Between Worlds at TAG Art Museum, Qingdao

I

Why Was It Necessary for Him to Walk out of His Studio?

Even if this creative method is not unfamiliar to people, there is still someone who will question such a “self-abusing” creative behavior, or regard his creation as a “sketch” in an extreme environment, but the wild remains a deep attraction to him. So why was it necessary for him to walk out of hisstudio? Where is the attraction of nature to man?

Honestly speaking, the history of outdoor creation has a relatively long development process in both China and the West when we sort through the history of art. China has had the word Xiesheng (“sketching from life”) since ancient times and it is mostly used in the field of flower-and-bird painting. Traditional Chinese painters pay attention to “reading thousands of books while traveling thousands of miles”. They seldom paint during their journeys, but they rely on “visual knowledge and memory,” namely the impression of natural landscapes and the schema experience of the ancient artists. The new tradition of sketching in the sense of modern art education occurred in the 20th century influenced by the wave of new culture of the May Fourth Movement, which draws on the sketching and description of objects vigorously advocated by Western painting. A group of painters who were interested in reforming Chinese painting had conducted realistic landscape sketching in nature and they stepped out of their studios and studies, came into contact with real life, and resolutely embarked on the road of sketching at the frontiers, Northwest China and rural areas. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, sketching has been associated with the source of development and creation, thus going deep into life, sketching from nature, and creating in nature have been vigorously promoted in art education.

Liu Shangying created his painting in Ngari, Tibet, 2014

Liu Shangying created his painting in Ngari, Tibet, 2014

Liu Shangying created in Ejina, Inner Mongolia, 2015

Liu Shangying created in Ejina, Inner Mongolia, 2015

In the history of Western art, the school of painting clearly regards “facing nature and sketching against scenery” as its creative principle can be dated back to the Barbizon school in the first half of the 19th century. The Barbizon school had a great influence on the painting of later generations. As an independent category, landscape painting gained the same important status as historical painting at that time. In addition, its expressive power of light and color and the expansion of language contributed to the emergence of Impressionism and became the spiritual source of Impressionist painting.

It can be seen from the process of artists walking out of their studios and walking towards nature that most of them pursue the truth, that is, they use their own bodies and eyes to understand, feel, and describe the real world, rather than passively obeying the principles of lifeless painting formed by their predecessors.

The development of art has already stepped out of the framework of reproducing reality, and gradually entered a pluralistic state with conceptual art as the mainstream since the 1960s. Liu Shangying’s artistic actions in the context of contemporary art are also the same. For him, the description of nature—that is, the visual part is no longer important. What is important is to paint in nature, and nature stimulates his perception. Accompanied by the creative process of the body’s continuous involvement, in the end, in the dilemma faced by contemporary painting itself, a new painting motivation or the possibility of painting can be found.

Liu Shangying’s Wildness Project work site at Red River Valley, Tuokexun County, Xinjiang, 2019

Liu Shangying at the work site in Altun Mountain, Xinjiang, 2021

Liu Shangying worked at the Tian Shan (also known as the Tengri Tagh) in Xinjiang, 2022

Liu Shangying once said: “Going far is to get closer to yourself. Distance strengthens one’s will, distance makes one simple, and distance reduces inertia and trivialities.” [1] The feeling of being alone in the wilderness, for him is both simple and rich. What fills his heart is no longer meaningless social labels or illusory fantasies, but real labor, and desires are reduced to the extreme, leaving only pure perception and physical repetition.

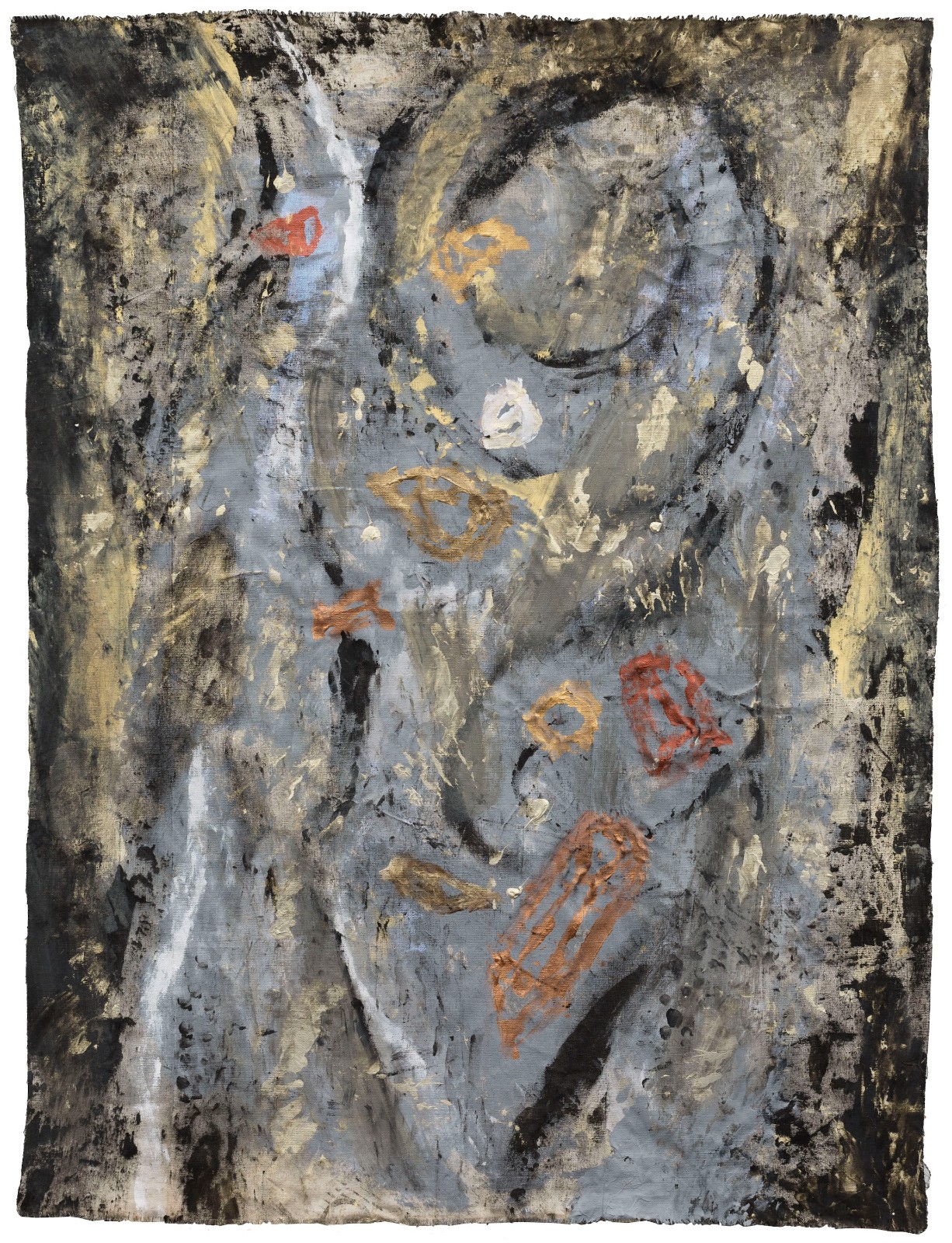

In the wild, Liu Shangying also often loses his judgment and feels at a loss. He describes his experience as a kind of “unreal reality.” A turning point came in 2011 when he traveled to Ngari, Tibet. In the world’s third-polar geographical environment, the oppressive aura made Liu feel the insignificance of human beings from the bottom of his heart. When he completed some small landscape sketches as usual, he suddenly fell into depression as the traditional landscape depiction and the original natural energy field were really irrelevant. His original expressions failed, and he realized he had to start over. He recalled that he fixed the canvas by the lake at the same time every day, and spent most of the time sitting there watching, two hours, three hours...just gazing, without any direction. He once wrote:

“During my stay at Ngari, I tried my best to find some kind of deep connection with it. I slowly experienced a rhythm, a kind of piety, and it gradually calmed me down from my restlessness. At that time, painting became a form of simple labor, a kind of farming, and it makes me feel at ease.” [2]

Magic of the Lake, Acrylic on canvas, 135×200cm, 2011

Marnyi Stone, Acrylic on canvas, 100×200cm, 2012

Sky Mirror, Acrylic on canvas, 200×380cm, 2013

Lake Manasarovarar No. 19, Acrylic on canvas, 95×200cm, 2011

Staying away from the hustle and bustle and civilization, returning to original nature, accepting its washing or even tearing process, and finally returning to a kind of authentic introspection, which is similar to a metaphysical spiritual search. Nature is not only an environment and external cause, but also a mirror to reflect the true self. After a long journey and self-examination, the internalization of the overall perception stimulates new possibilities of language and spirit, thus producing some “meaning.”

II

The Two Sides of Natural Presence and Division

Some critics compare Liu Shangying’s creation with “action painting.” Representatives of action painting, such as Jackson Pollock and Kazuo Shiraga, rely on improvisation, intuition and physical experience in the process of painting. Pollock once said that he didn’t realize what he was painting when he started to paint, and only after he finished it did he understand what he did. This state of selflessness makes “self” become his exclusive belief. Compared with Liu Shangying’s paintings, the body intervention, non-reproducibility, and unconscious state reflected in this state do have similarities. But from the perspective of painting concepts and forms, Liu Shangying’s artistic practice is fundamentally different from action painting. Different from their status as studio artists, Liu Shangying’s painting form is firstly as a “field artist”, and secondly, his painting process emphasizes communication with nature, relying on the stimulation of the external environment to break the “stability” of daily work, based on nature’s remolding influence on human consciousness among the environment, therefore it explores the new value of painting with an “antiempirical” attitude.

Although he knows that his painting form is relatively special, Liu Shangying still believes that his creation is still in the category of traditional art, not conceptual painting in a complete sense, but a little more extreme than traditional art. For instance, he keeps entering the wild though no one lives there, it is a place that may be difficult for animals and plants to survive normally, and thus he confronts painting under extremely uncomfortable conditions. Most people would not choose this way, or even understand it. But for Liu Shangying, whenever he enters this environment, he can unconsciously form a certain connection with the wasteland. What exactly does this inexplicable feeling point to?

Liu Shangying seldom thinks about the forward-looking nature of painting, but always thinks about the source of painting, what is painting itself? Anthropologists and art historians have found that modern art was inspired by primitive art. So what were the motivations for ancient ancestors to make petroglyphs or carvings in prehistoric art? Whether they were for witchcraft, commemoration, or recording, the academic circles have different opinions, but it was evidenced that painting was produced earlier than writing. Before there was writing, human communication took place through the conversion of paintings (images) into pictographs, and finally into writing. It can be seen that painting is an innate instinct of human beings. More than 10,000 years ago, primitive people painted on the natural cliffs, and modern people who discarded the existing cultural experience and painted in the deserted wilderness, all point to human instinct.

Valley and Mountain exhibition view, Tian Shan, Xinjiang, 2022

However, modern people are not primitive people living in the wilderness after all. The stimulation of “instinct” and the pursuit of “self” rely on two sides of the split: on the one hand, the development of modern technology and material conditions makes it possible to paint in the heart of the wilderness. While enjoying the convenient life of urbanites, on the other hand, he always has “doubts” about the home of the spirit of modern people, which prompts Liu Shangying to stay away from the crowds and walk towards the wilderness without any people. But he still has a mundane side that he cannot get rid of. For example, he has to consider the feelings of his family members, and he cannot do whatever he wants. Therefore, he often wanders between the city and nature, maintaining a “nomadic state.”

Longing for mountains and fields, living in seclusion and seeking ambition may be the common pursuit of a large number of intellectuals. At the age of 48, the British art critic John Berger moved to Quincy, a village with a population of only 100 in Savoie, France, where he lived in seclusion for more than 40 years to the end of his life. The movie The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger(2016) records precious images of his later life, working like a farmer in the mountains, and experiencing the philosophy of life like European farmers, which includes the experience of human beings in nature, the relationship between humans and animals. A relaxed life isolates him from a more complex and broader social life. Freedom and isolation are two sides of the same body.

Henry David Thoreau described people’s expectations for integration or returning to nature in Walden: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” With the presence of nature, the human soul can be stretched, and the body and mind will return to true freedom.

Exhibition View at Ejina in Inner Mongolia in 2017

III

“I don't want to be thought of as a wilderness painter”

Painting and walking are two parallel lines in Liu Shangying’s art. Curator Guo Xiaohui deeply analyzed the concept and history of “walking” from a theoretical perspective. She believes that Liu Shangying’s creation resonates with Walter Bendix Schoenflies Benjamin’s idea, that is, the image of a contemporary “wanderer.” The wanderer in the modern city is not only the product of modernity, but also the observer and resister of modernity, just like what Charles Pierre Baudelaire called “the painter of modern life.”

In the past twelve years, Liu Shangying has traveled more than 120,000 kilometers. The five nature painting projects are related to each other but they also remain relatively independent. Each experience and feeling is completely different. From “l(fā)ooking up” at the sky in Tibet, “l(fā)ooking down” at the land in Ejina, to “rebirth from desperate situation” in Lop Nur, “uncovered land” in Altun Mountain, and finally the “warm journey” back to Tian Shan (also known as the Tengri Tagh).

Wilderness Project No. 21, Acrylic on canvas, 356×3770cm, 2019

Wildness No. 17, Acrylic on canvas, 136.5×104cm, 2019

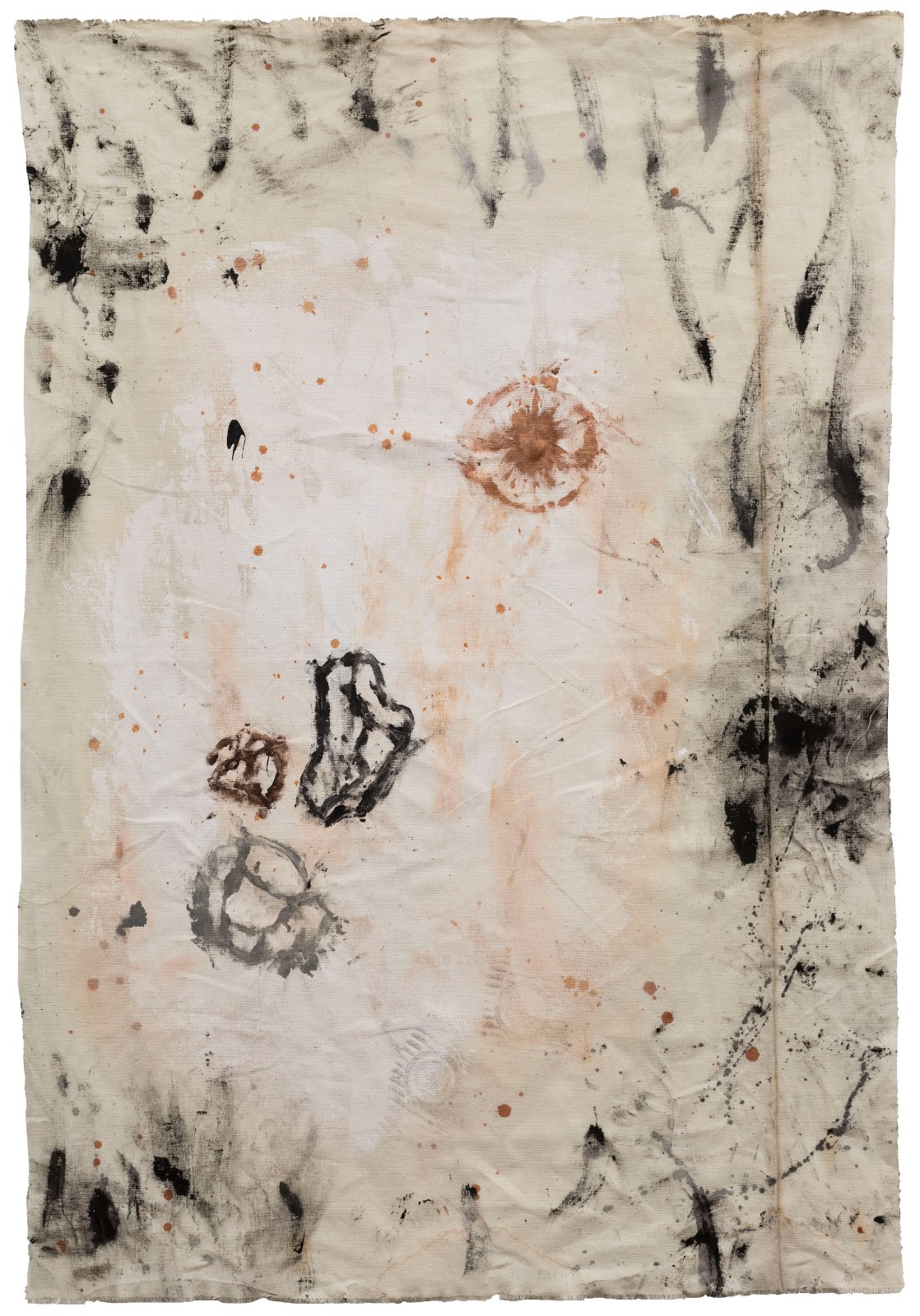

In Ngari, Tibet, the magical light in the hinterland of the plateau keeps the artist’s eyes on the distance, and he constantly feels the miracles coming from a “l(fā)ooking up” perspective. This is the starting point of abandoning his past experience. But in Ejina, Inner Mongolia, the desert is full of fragments of Populus euphratica, which keep people focused at close range, and they feel the energy of the earth full of wind and sand from a “l(fā)ooking down” perspective. Two years later, he entered the “sea of death” Lop Nur, a desperate situation where no grass could grow, and painted the most shocking chapter among the five projects. The desolation there makes people tremble. When Swedish explorer Sven Hedin rediscovered the ancient Lop Nur ruins in 1901, he deeply felt that everything in the world here would eventually disappear or pass away. [3] In such a horrible wasteland, Liu Shangying went deep into it twice. His painting process went from resistance to pain, further to compliance, reconciliation, and finally blending with it. A series of unprecedented psychological experiences brought him back to life. Spiritual self-sufficiency is achieved in the awe and symbiosis of nature.

Wilderness No. 20, Acrylic on canvas, 137.4×95.5cm, 2019

In 2021, Liu Shangying came to Altun Mountain. The seemingly majestic land hid more dangerous and unknown threats. In the difficult coexistence with the barrenness, he constantly refreshed his cognition and gave birth to artworks like “Footprint” and “Rainbow” that cannot be found but obtained from the integration of life and nature. In 2022, he came to Tian Shan (also known as the Tengri Tagh), Xinjiang. The beauty of the fairy tale world made people retreat. Unlike his struggles of several projects in the past, he experienced the warmest part between man and nature in the process of getting along with the Kazakh aborigines. Thus he started again with his own body and perception.

Liu Shangying has a habit of recording painting scenes in his videos. In the camera, he is like everyone in the world, walking alone in the vast desert. He bows devoutly all the way, offering his body, words, thoughts and everything to heaven and earth. His creative method allows nature to participate comprehensively, with flying sand, sudden hail, and raging wind. He climbs, covers, and buries with bare hands, sometimes sits quietly, sometimes crawls, touches the natural forms with canvas and paint...

On-site Exhibition View of "Shaziquan and Rainbow at Qimantag", Altun Mountains, Xinjiang, 2021

Creative Scene of Footprint at Altun Mountains, Xinjiang, 2021

With labels like “wilderness painter,” Liu Shangying has gained a lot of attention in recent years. He admitted that his original intention did not consider creating in a particularly extreme environment, but only hoped to paint in relatively primitive and real nature. The media and the public always need stories. The legendary experience in the wilds of nature attracts people’s attention, but it is not what the artist really wants to convey. Although the exhibition also displayed a wealth of video materials and objects with traces of life in the wilderness, his intention is not to show the “spectacles” that people expect, but to invite the audience to enter the tranquility and mystery of the wilderness at night and to appreciate some unattainable spirit in space and time.

Novalis said: Creating art is to introspect oneself, imitate oneself and shape one’s own nature. Over the past decade, Liu Shangying has always followed the inspiration and guidance of a “deity” in his heart. His unrealistic search, the vague but firm thing, is his deep belief in nature, life and painting. He hides in the wilderness, and what he wants to rebuild again and again is the connection between his true self and the world.

Exhibition View of Walking Between Worlds at TAG Art Museum, Qingdao

Notes:

[1] Liu Shangying, Who’s Painting, exhibition catalog, produced by Star Gallery, 2021

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sven Hedin (Sweden): The Wandering Lake Into the Heart of Asia (Volume 2), p107

Image Courtesy of the Organizer.