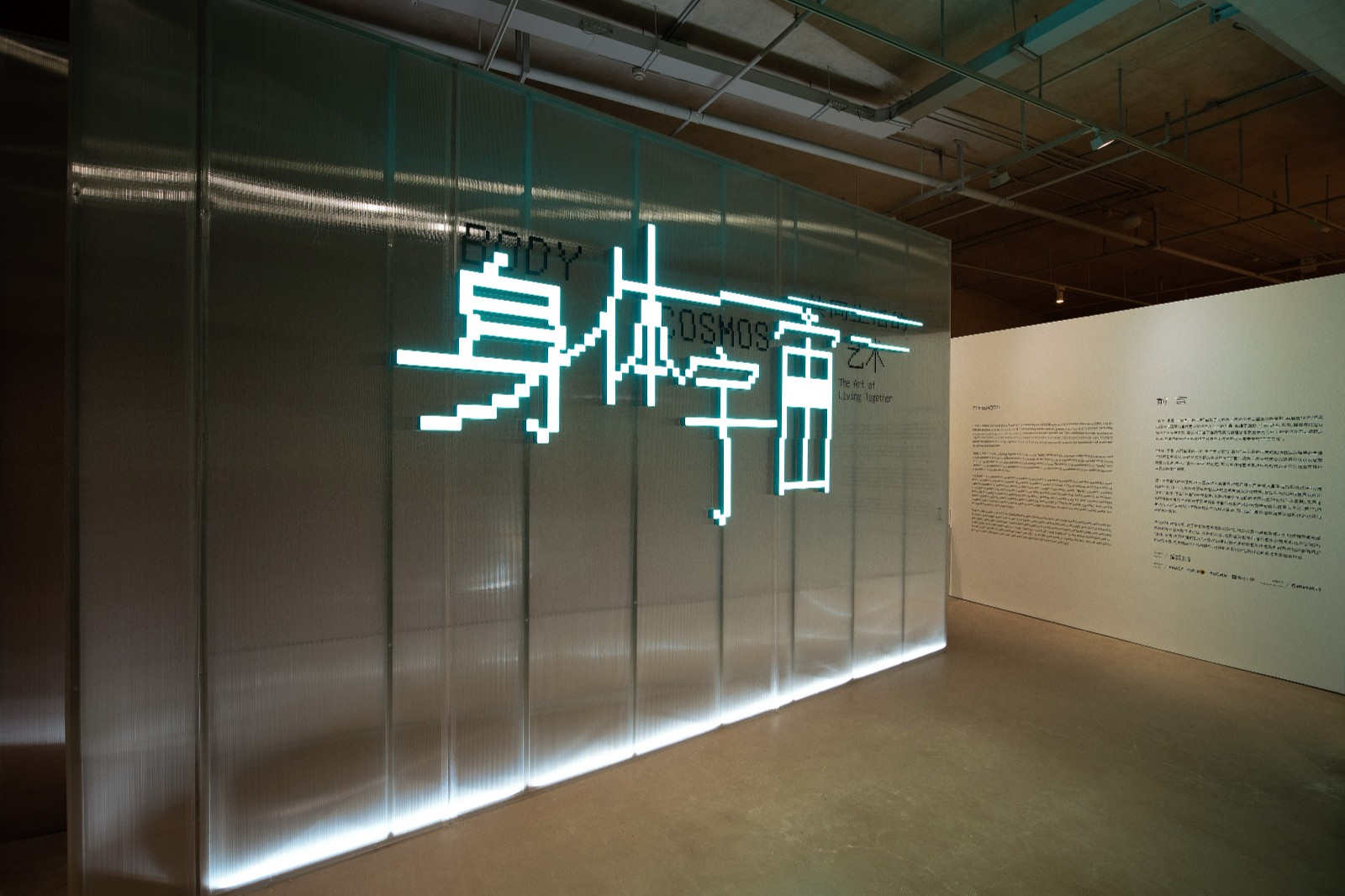

Editor’s note: On 29th April, Xie Zilong Photography Museum’s annual exhibition “Body Cosmos: The Art of Living Together” kicked off in Changsha. In the past few years, how art museums have functioned as “Internet influencers” has been a controversial issue that has often been raised and discussed. As one of the art institutions labeled as “internet celebrity”, under the influence of the pandemic, Xie Zilong Photography Museum (abbr. XPM) has to confront the challenge in terms of a sharp drop in visitors and begin to think about the problem of its long-term development. Curated by Dong Bingfeng, who serves as the Academic Director of XPM, the exhibition “Body Cosmos: The Art of Living Together” gives its unique answer to respond to the problem. When an increasing number of traditional art museums are trying to become “internet celebrities”, XPM turned to present more professional, cutting-edge, and in-depth contemporary art exhibitions instead, trying to participate in a discussion on critical issues in the contemporary art world.

Editor’s note: On 29th April, Xie Zilong Photography Museum’s annual exhibition “Body Cosmos: The Art of Living Together” kicked off in Changsha. In the past few years, how art museums have functioned as “Internet influencers” has been a controversial issue that has often been raised and discussed. As one of the art institutions labeled as “internet celebrity”, under the influence of the pandemic, Xie Zilong Photography Museum (abbr. XPM) has to confront the challenge in terms of a sharp drop in visitors and begin to think about the problem of its long-term development. Curated by Dong Bingfeng, who serves as the Academic Director of XPM, the exhibition “Body Cosmos: The Art of Living Together” gives its unique answer to respond to the problem. When an increasing number of traditional art museums are trying to become “internet celebrities”, XPM turned to present more professional, cutting-edge, and in-depth contemporary art exhibitions instead, trying to participate in a discussion on critical issues in the contemporary art world.

Changsha is a city with a strong sense for entertainment. There has never been a shortage of interesting places to visit, and the choice of art museum is only a part of it. Compared with metropolitan cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, the soil for contemporary art is undoubtedly not fertile enough in Changsha. Therefore, when an art museum that is popular in the internet sphere wants to present the most cutting-edge contemporary art exhibition, both the concept of pioneering and risks are obvious. Can an art museum labeled as “internet celebrity” hold in-depth exhibitions? Can it make good use of its visitor base to achieve the educational goals of contemporary art? The exhibition “Body Cosmos” provides us with a typical sample from observation.

As far as the exhibition title is concerned, the curator Dong Bingfeng elaborates in the exhibition forward, “‘Body · Cosmos’ initiates from a global perspective, applying art practices from different historical periods over half a century, to contemplate and constantly explore the complexity and its major debates on contemporary art that intertwine itself within the historical judgments and contemporary concepts. In this regard, ‘The Art of Living Together’ is an active response and a bold experiment to issues such as technological changes, political life and ethical values under the context of the current turbulent reality.”

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

This paragraph easily reminds us of the 59th Venice Biennale which kicked off recently. Its theme also features “the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; the connection between bodies and the Earth”. If we admit that the 59th Venice Biennale has focused on some key issues that are confronted by human beings, then in a sense, the exhibition in XPM can also be regarded as a specific response to these issues. Furthermore, it evidences the characteristics in a Chinese context. “Body Cosmos: The Art of Living Together” gathers 14 groups of contemporary artists from China and abroad, the artworks range from the latest creation in the last year to the creation concerning the early moment of contemporary art in the 1980s.

Exhibition View of Feng Mengbo’s “My Private Museum”

Exhibition View of Feng Mengbo’s “My Private Museum”

Feng Mengbo, “Apes”, Color Photography, 100.5×67cm, 2012

How could cutting-edge art issues be closer to the viewing habits of the audience from an inland city? In the first chapter, the exhibition begins with the memory, taking Feng Mengbo’s “My Private Museum” series as the starting point. Feng recorded the former site of the Shanghai Natural History Museum, presenting a series of typical Chinese interior spacial elements, such as wood panes, green dados, and tiled floors. It is these visual elements that constitute the collective memory of generations of Chinese people. Feng’s work acts as a “double screen”—the viewer can observe a traditional museum in a contemporary art museum, and such a dislocation reveals a structure. Museums are often regarded as modern temples that preserve everlasting things, but Feng reminds us that museums and specimens will eventually become ruins. Besides, the concepts of nature that they symbolize are not immutable laws, and that knowledge, history, and culture can be perceived ultimately only through our memories.

Ayoung Kim, “Petrogenesis, Petra Genetrix”, Video (Still), 6 Minutes 50 Seconds, 2019、2021

Cao Shu, “400 Million Years Ago, It was The Ocean, and 400 Million Years Later, It is The Desert”, Pole, Model Paint, Acrylic, Wire, Raspberry Pi 3b, Screen, Special Clip, 20×16×11.5cm, 2021 Exhibition View

Exhibition View

Bruno Latour tells us that knowledge of objects is artificially constructed and that they themselves do not have an absolutely legitimate foundation. In this regard, scientific knowledge has no fundamental difference from religious belief. Following Feng Mengbo’s intimate introduction, Ayoung Kim’s “Petrogenesis, Petra Genetrix” presents just such a notion with a larger historical dimension by mixing traditional beliefs, geological investigations, and modern museum discourses, continuing the mineral animism in the Mongolian tradition, thereby creating a set of exaggerated myths.

Cao Shu’s “Past and Future Observer” utilizes video installations to provide the body with a perceptual experience that transcends the limitations of reality, and attempts to re-examine our understanding of nature and history through this perception. Such an interpretation also echoes the Gaia hypothesis and the concept of the “Anthropocene” supported by Latour, pointing to a non-anthropocentric nature. Gaia is an image of the earth, which means a new view of life. The hypothesis proposes that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form the whole planet. “We have never been modern.” So said Latour. Modernity makes us believe that nature is an external object, but we are in fact dealing with a “quasi-object” that is both constructed by social discourse and maintains its own agency.

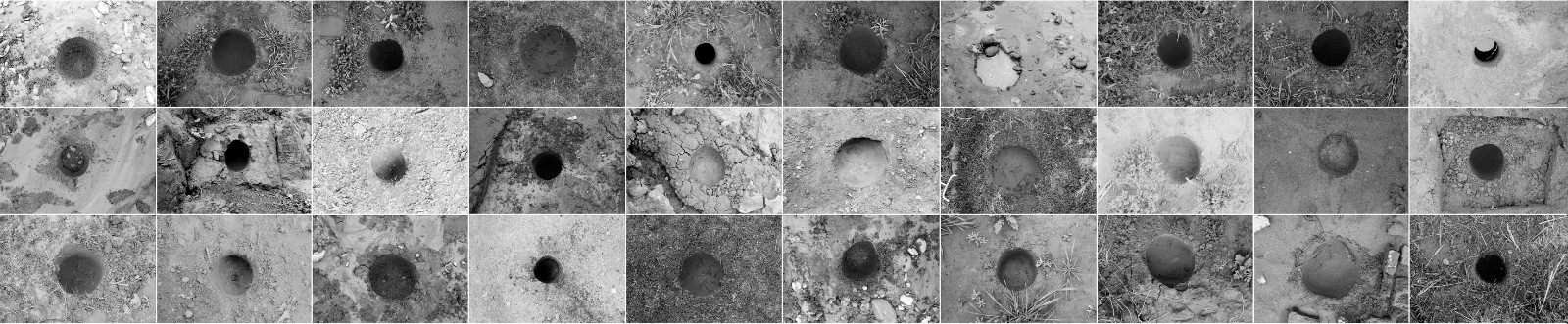

Zhuang Hui, “Longitude 109.88 Latitude 31.09”, Black and White Photo and Video,Variable Dimensions, 1995, 2008

Exhibition View of Zhuang Hui’s “Longitude 109.88 Latitude 31.09”

Exhibition View of Zhuang Hui’s “Longitude 109.88 Latitude 31.09”

Regarding the accurate location in the title of Zhuang Hui's “Longitude 109.88 Latitude 31.09”, the better-known name is the Three Gorges. In 1995, when the Three Gorges project was just initiated, Zhuang Hui chose three locations for drilling in the main natural environment of the Three Gorges Dam area. Twelve years later, he asked the photographer to return to the spot to photograph the hole that had been submerged in water at a depth of 100 meters. What could be more characteristic of a quasi-object than this piece of work? Our perception of the site is thoroughly social—it is known as a water junction, an engineering marvel, a modern wonder... but beyond that, it is also part of Gaia. It confronts traces, dams, or holes what we humans have left on it. When gazing at these images, can we free ourselves from the illusions of modernity?

Tactile Art (Wang Luyan & Gu Dexin), “Tactile Sensation”, Photographic Paper, 16.5×16.5cm×16, 1988

Exhibition View of “Tactile Sensation”

Exhibition View of “Tactile Sensation”

The development of technology has brought us into the age of Anthropocene. The fact that we are the subjects most able to influence and transform our environment and ourselves thus making technology in turn a quasi-object. The exhibition’s section “Body and Technology” presents how technology becomes a part of our body, both the reality, the symbolic order that shapes us and even the seedbed of our imagination. “Tactile Sensation” was created in 1988 by Tactile Art (Wang Luyan & Gu Dexin), representing a specific attitude of that era—the body is an object that needs to be transcended, and aesthetics and ideas are purified from it. Thus, the technique of photography becomes an experimental means for the artist, leading to a Platonic subject, and a world of the avant-garde and progressive.

Antje Ehmann & Harun Farocki, “Labour in a Single Shot: Workers Leaving Their Workplace”, Video, Variable Dimensions, 2011-ongoing

Antje Ehmann & Harun Farocki, “Labour in a Single Shot: Workers Leaving Their Workplace”, Video, Variable Dimensions, 2011-ongoing

Hu Jieming, “Space Exploration”, Digital Photo, Variable Dimensions, 2022

Miao Xiaochun, “Limitless”, 3D Computer Animation, 11 Minutes 15 Seconds, 2011-2012

Miao Xiaochun, “Limitless”, 3D Computer Animation, 11 Minutes 15 Seconds, 2011-2012

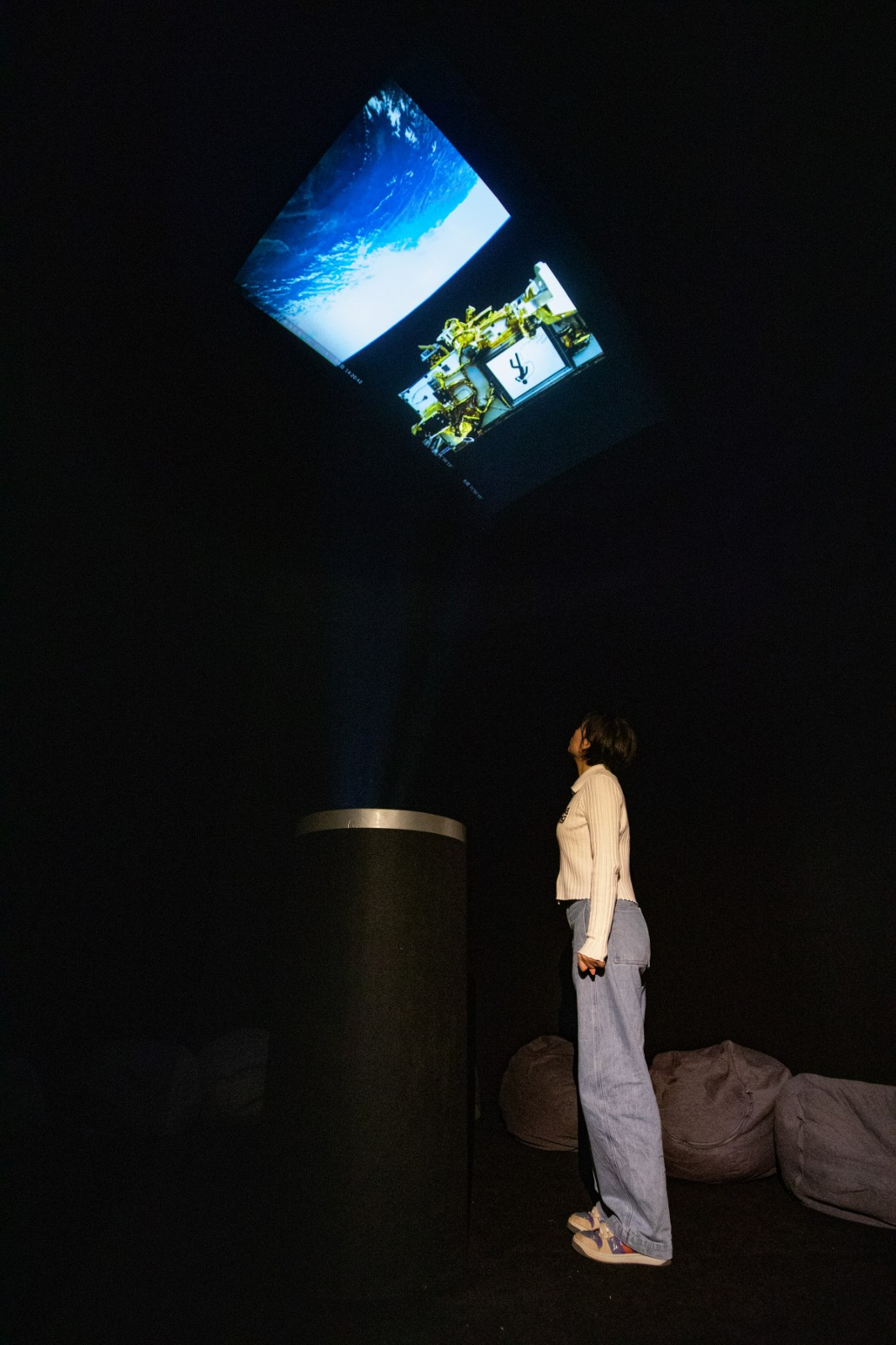

Nowadays, we rarely understand the subject and the body in a Platonic way. Technological creations like smartphones no longer separate our soul from the body, but instead, the technology itself acts as a wedge, implanting and piercing our body. During the pandemic, we have to scan health codes in every public and even non-public space which results in us having taken smartphones as our organs (from another pessimistic point of view, today's “disabled people” who lack this organ will face the existential crisis immediately). Technology as a body also means that it imprints its own disequilibrium and difference on us. Such a melancholic form of the metaphorical clue in Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki's “Labour in a Single Shot” (2011-2014). The theme of "Workers Leaving their Workplace” corresponds to the first moment in the history of video, the Lumière brothers’ “La Sortie de l'usine Lumière à Lyon” (1895). Miao Xiaochun’s video poetry and Xu Bing’s ongoing series "Books from the Ground” demonstrate that video as a visual technique, provides the basic framework for the subject and enables new aesthetics. While Hu Jieming’s "Space Exploration” Project may be the most intuitive work in the section because it takes the architecture of XPM as the subject. Comparing it with the old museum photographed by Feng Mengbo, we may realize how contemporary art museums reshape our visual experience. On the one hand, we are no longer disciplined to look through glass windows, but to let our eyes wander freely in space; on the other hand, this free line of sight is closely related to a camera lens.

Xu Bin's work, Video Installation, 1 Minutes 30 Seconds, 2021(The work is still in progress.)

Liu Chuang, “Can Sound be Currency?”, 2k, Color, Stereo, 19 Minutes 43 Seconds, 2021

Liu Chuang’s “Can Sound be Currency?” reveals the underlying structure of the cutting-edge parts of today's scopic regime to us. Virtual currency (whether fungible or non-fungible) is a popular industry in the world today, including the art world, but its digitization often obscures the real labor behind it, and a lot of electricity consumption and carbon emissions are invisible. The artist examined the “migration” of “mining" a virtual currency in southern Asia in an anthropological way. In order to obtain cheaper sources of energy, bitcoin mines would migrate between Southeastern China, Western China's Xinjiang region, and Inner Mongolia as the season changes. The "metaverse" that relies on this system is regarded as a bright prospect for future art; however, we have not yet faced up to the physical body of this digital world.

Exhibition View of Liu Xin’s “Ground Station ”(right side), UV-led Print, Metal, 35.6×27.9 cm, 2020-2021

The third part of the exhibition does turn to the literal universe. Liu Xin’s work is the most space-inspired part of the whole exhibition. Using a simple antenna made of brooms and coat hangers, the artist regularly receives signals from a weather satellite launched by the United States in the last century, and finally transforms it into a sound and light installation. Let us recall again the traditional museum at the beginning of the exhibition. These images from space are also very different from the usual displays in planetariums. We can also take an inner, empirical perspective on the universe without abandoning science, society, and art.

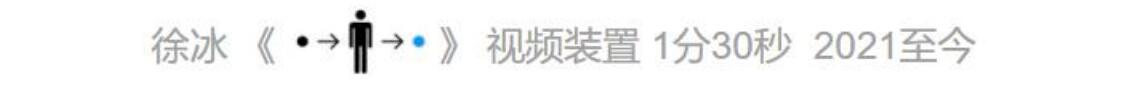

Guo Fengyi, “Bagua Tower”, Colored Ink on Rice Paper Mounted on Cloth, Hanging Scroll, 151×43.4 cm, 1992

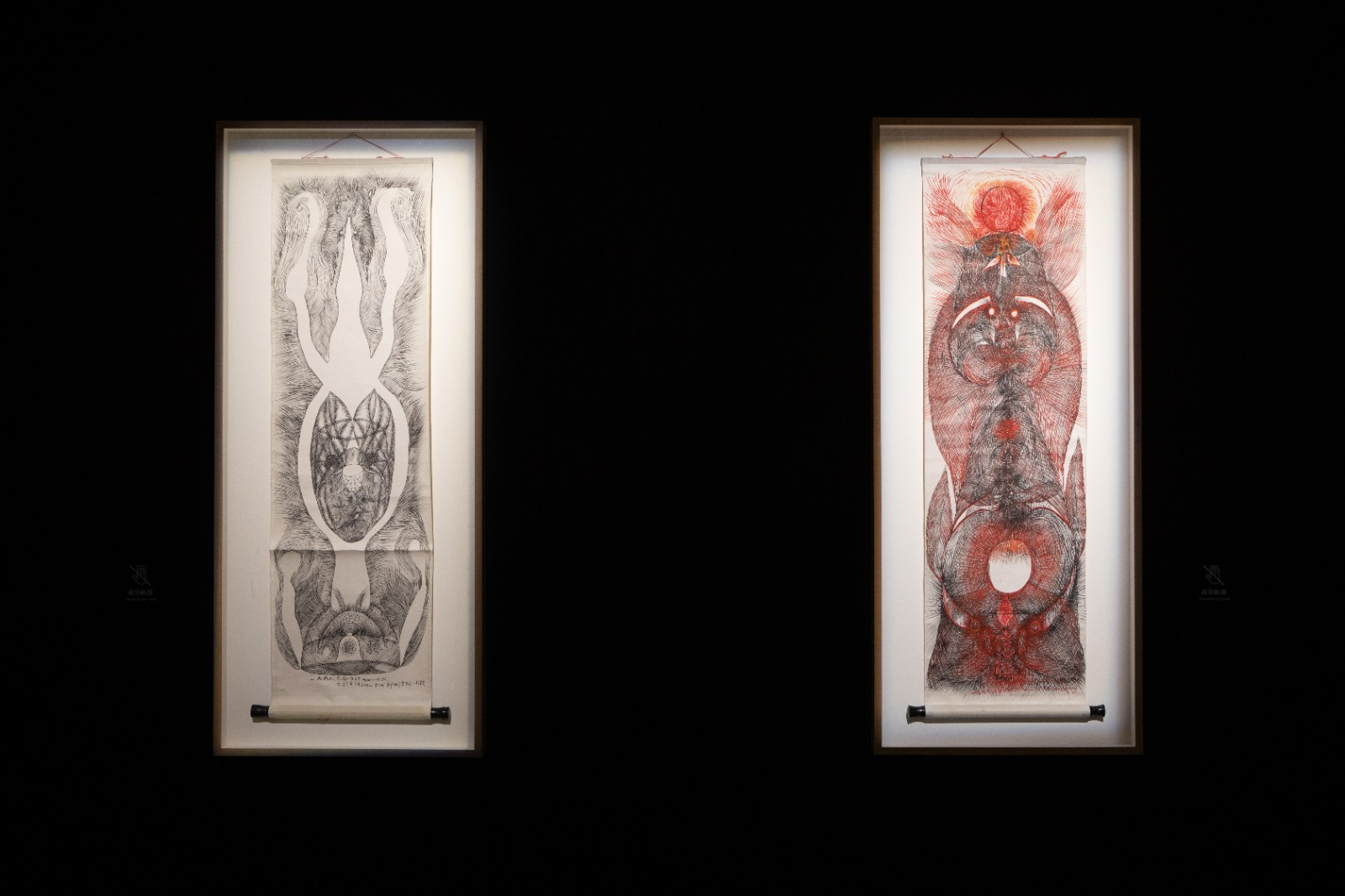

Zheng Guogu, “Brain Line-Senior Moral”, Oil Painting, 134×106cm, 2017

Exhibition View of Zheng Guogu’s Work

In fact, what we call space today is only a very recent object in the conceptual history of the “universe”. There is coherence between our view of the universe and our view of the body. As Donna Haraway famously argued, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of the machine and organism. While Bruno Latour also emphasized that we must reconsider the history of humans and the universe from the perspective of Gaia. Guo Fengyi's work invokes traditional Chinese cosmology and creates a series of personally imagined images through Chinese painting. These bold images echo the traditional character of image-making as a means of sensibility. Zheng Guogu’s “Liao Garden” series shows a reverse cyberization path. During the creation, the theme of the project has returned from video games to traditional gardens, which reinforces the interaction between humans and the outside world. This de-digitized space has more cyber features than virtual space, where the boundaries between body, architecture, and nature become more blurred than the everyday life in the digital age.

Mao Chenyu, “Anti-Rural China”, Film, 71 Minutes, 2021

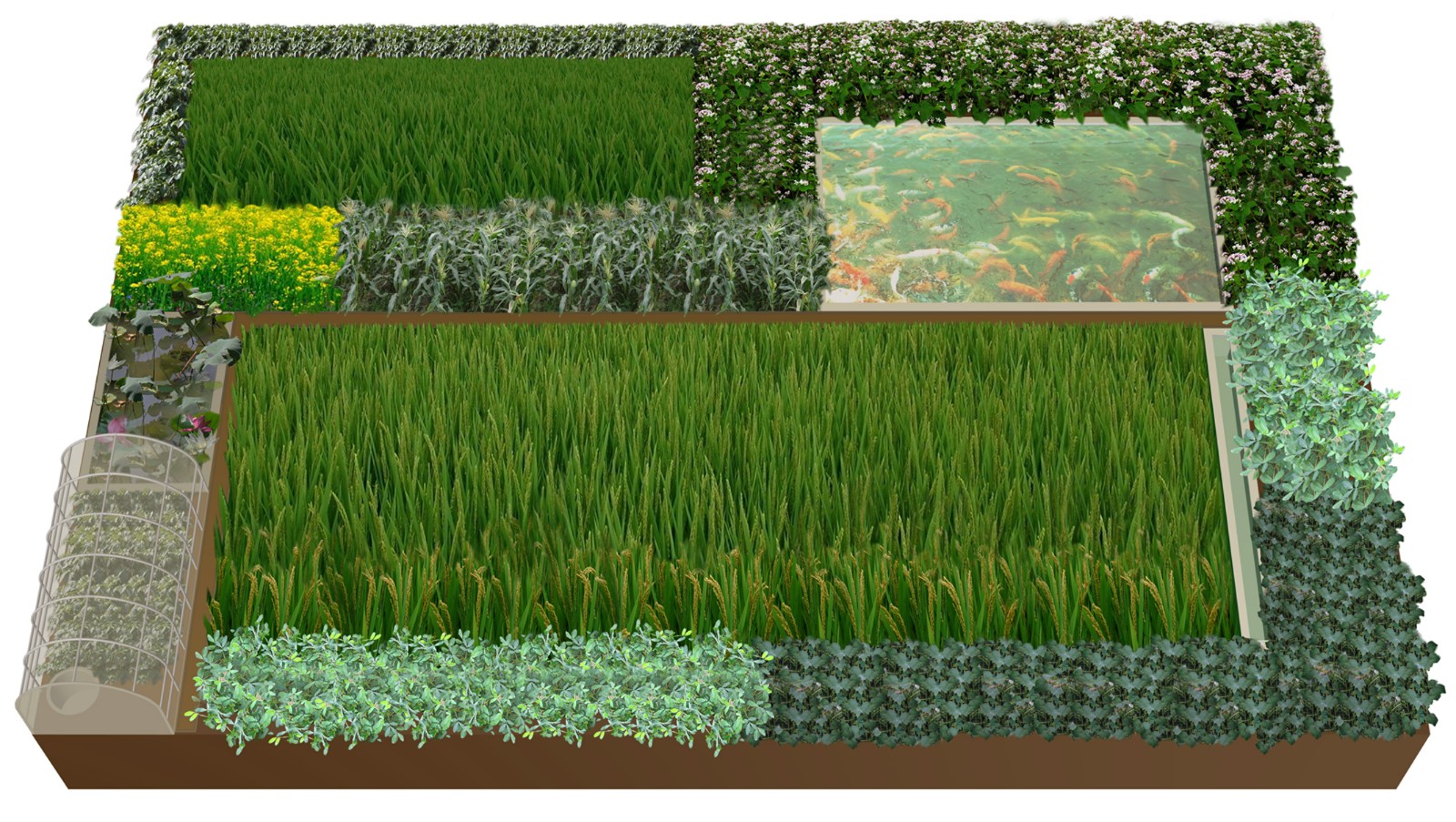

Mao Chenyu, “Anti-Rural China”, Film, 71 Minutes, 2021 Exhibition View of Mao Chenyu’s “Documenta for the 20th Anniversary of Paddyfilm”

Exhibition View of Mao Chenyu’s “Documenta for the 20th Anniversary of Paddyfilm”

Mao Chenyu’s “Paddyfilm” series might be the most radical group of works in this unit, and it is also most directly echoes Latour’s ecological theory. In a series of videos, Mao Chenyu reformulates traditional texts, modern production, myths of patriarchy, and notions of “rural China”. Following Bernard Stiegler, Mao Chenyu defined the problem in today’s modern agriculture as “entropic agriculture” and maintained the landscape of today’s capital world with a Georges Bataille-style “l(fā)a dépense”. We have mentioned several obscure and complicated terms herein. However, introducing them is necessary for encapsulating these hour-long videos. Like Latour, Mao Chenyu reminds us of our responsibility in the age of Anthropocene today. The traditional field of agriculture cannot be ignored.

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

We have already mentioned all the artists in the exhibition. It is absolutely cutting-edge in terms of the exhibition perspective, especially for an inland city like Changsha. The exhibition’s subtitle “The Art of Living Together” is aimed both at the participating artworks and the audience at the museum. The exhibition, which opened shortly after the last wave of the intense pandemic in Changsha, may also be the first time for many viewers to revisit the museum. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, we have more than once experienced the “trauma of the real”. The fear of being in lockdown reveals how firmly our physical bodies occupy their place in our subjectivity, rendering all ancient assumptions of mind-body dualism weak. Meanwhile, the pandemic has shown us in a brutal way as to how the nature of the planet treats human life equally, making distinctions of gender, race, class, etc. secondary. Although in human society, some of them are still more vulnerable than others for reasons that are not natural. Thus, “The Art of Living Together” is transformed into a grand human proposition.

There is more than one way of telling a story, and countless traces of words, codes and power are inscribed on our bodies. As far as a video/photograph-based art museum is concerned, choosing the body as the exhibition theme has a positive significance. “The body on the screen is illusory”—this phrase has become untenable today. At this moment, the virtual body symbolized by the health code on the mobile phone screen is protecting the legitimacy of our physical body. In times of crisis, how to regain the vitality of the body is particularly important. It should be noted that Nietzsche, Foucault, and Deleuze, the three key figures in the spectrum of body theory, all continued to encounter painful bodies throughout their lives.

One more interesting accident was that, in conjunction with Mao Chenyu’s video, a small paddy field was prepared in the exhibition hall. However, when the author visited the exhibition, this paddy field disappeared—it was moved outside as the paddy seedlings could not adapt to the environment of the exhibition hall and began to wilt. Artworks open up various avenues for us, offering the possibility to escape the cage of existing discourse, power, and social representation. In a sense, the paddy field shows us its existence as a suffering body, which is not disciplined in the name of art. In the face of art and nature as well as crises in today's world, we do need new solutions for living together.

Text by Luo Yifei, translated by Emily Weimeng Zhou, edited by Sue.

Image Courtesy of the organizer.