“Maurizio Cattelan: The Last Judgment” is the first solo exhibition in China by Maurizio Cattelan (b. 1960, Padua, Italy), one of the most popular and controversial figures on the international contemporary art scene. At Art Basel Miami Beach in December 2019, he became a widely known artist throughout the world for a banana duct-taped to the wall of a gallery booth. When confronted with such an artist like Duchamp, we naturally have our expectation of what will impress us. Actually, we were shocked by the exhibition as it presents a diversified wonderland of fantasy where the audience can always find something that may touch them; meanwhile, it exposes his bantering expression that people in China are not acclimatized to and its criticizing strength is also weakened.

Animals: the Cruel Wonderland of Alice

Maurizio Cattelan, Felix, 2001, Oil on polyvinyl resin, fiberglass, 792 × 183 × 610 cm, Yuz Foundation Collection. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Felix, 2001, Oil on polyvinyl resin, fiberglass, 792 × 183 × 610 cm, Yuz Foundation Collection. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

As soon as we walked into the gallery, we saw a set of huge cat skeleton confronting us, with its limbs splayed out, its back hunched and its tail taut showing its aggression. The brochure for the exhibition interprets the installation as it “encourages the spectators to think about the reality and fiction as they see it,” and in the same brochure, Cattelan hopes that the audience can “become Alice in the Wonderland, and make art either your friend or your enemy.” Both Cattelan and UCCA Center for Contemporary Art know well that an exhibition should deal with realistic issues during this increasingly developed age of media: building a theme park is better than a modernist “white cube”, as it is more lively than a “Dinosaur Park” in a Natural History Museum but it is more serious than a “Jurassic World” at Universal Studios.

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

Animals come first in this theme park on art. Cattelan’s animals may involve both real and fictional characters but this has nothing to do with the representation in the art context. These animals in the exhibition hall are either specimens or imitation models, all of which are highly realistic, for the purpose of building a dream vision. A huge cat, an elephant in white robe, horses hoisted and plunged into walls, skeletons that act out Grimm’s fairy tales... these are the animals that Alice might encounter in Wonderland, and they are also what we may encounter in our dreams. This dream follows the imaginative mechanism of projection, and among all imaginary phenomena, love is always the most prominent one. Thus we have found love in the titles of many works. But the artist was not trying to arouse our love or desire for animals, animals in his work resist our comprehension of them in zoos or circuses as he demands us to relate them in our imaginary selves, to reflect on ourselves as “human beings.”

Maurizio Cattelan, Love Lasts Forever, 1997, Donkey, dog, cat, and rooster skeletons, 186 × 120 × 60 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Love Lasts Forever, 1997, Donkey, dog, cat, and rooster skeletons, 186 × 120 × 60 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Not Afraid of Love, 2000, Polyester styrene, resin, paint, fabric, 205 × 312 × 137 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Not Afraid of Love, 2000, Polyester styrene, resin, paint, fabric, 205 × 312 × 137 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

We often fantasize about flying in the air like a bird or swimming in the water like a fish. In fact, this fantasy reveals the inner repression of the image of “man.” Giorgio Agamben regards the relationship between animals and humans as a key issue in history. In Agamben’s view, it is the “Anthropological Machine” that constantly creates people within civilization. Humans are created through opposition to animals and non-humans. This mechanism works through exclusion and inclusion. At the center of the “Anthropological Machine” is a zone of indifference, a space of exception and a wonderland. The distinctions and connections between people and animals, human and inhuman, the speaking beings and living beings are entangled here. While quoting Plato, Julia Kristeva calls this region as “chora,” which preceded the birth of language, and preceded the symbolic order. If all goes well, Cattelan’s animals will take us into the Wonderland, where we can communicate with the animals, play with them as Alice and let go of the burdens that the symbolic order imposes on us.

Maurizio Cattelan, Novecento, 1997, Taxidermied horse, leather saddlery, rope, 201 × 271 × 68 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Novecento, 1997, Taxidermied horse, leather saddlery, rope, 201 × 271 × 68 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2007, Taxidermied horse, 300 × 170 × 80 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

But the Wonderland was not just beautiful as it appears, it conceals more cruelty as well. Alice eventually left the Wonderland, just as Wendy in Peter Pan left Neverland and entered the order and laws of human society. In Lacan’s psychoanalysis, the subject’s passage from the imaginary to the symbolic is accompanied by the acceptance of the prohibition and the creation of new desires. In Kristeva’s opinion, “chora” is related to the image of the mother, who is the initial object of desire in one’s growth: we originally desire the love of the mother, and then desire to break away from the mother to form the subject (Cattelan left an image of his early performance work Mother on the wall). The symbolic world intervenes with the image of the father, which not only causes castration but also provides the subject with new desires. In Cattelan’s work, a horse is the most prominent representation of this relationship. While reviewing the history of art, the horse has always been a symbol of heroism and power, as well as a symbol of masculinity. In Freud’s famous “Little Hans” case study, Little Hans’ fear of horses came from the tense relationship between him and his father. From art history to universal history, from family to country, the symbolic world as the big Other places its own desires beyond the subject. In the exhibition, Cattelan’s three horses all deny the traditional ideal image of majesty and power. Like Little Hans, the horses here symbolize failure, pain and fear, which the subject must face in the symbolic order.

The division between man and animal also determines the question on God, and The Last Judgment—the title of the exhibition—signifies a moment when a new image of life was born. In the works about love, the real and the imaginary maintain an intimate and delicate balance while in the works about failure, the real and the symbol are painfully intertwined.

Maurizio Cattelan, Mother, 1999/2021, Mural, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Mother, 1999/2021, Mural, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Death: The Delicate Distance from Abjection

Whether they are specimens or skeleton models, Cattelan’s animals are implicitly associated with corpses: “The Musicians of Bremen” in Eternal Love (1997) appear as skeletons, in Not Afraid of Love (2000), the elephant is a ghost. The fairy tale atmosphere of Wonderland is gone in Bidibidobidiboo (1996), which is itself an irony of Cinderella’s fairy tale, under the magic of the fairy godmother in the title, living in a lower-class Italian family, a squirrel committed suicide using a pistol. It is on the brink of abjection which Kristeva uses to categorize the world such as inside/outside, animal/human, animate/inanimate and life/death, and it was born where the boundary between the two breaks from each other. The corpse is the most prominent abjection, not only because it is a sign of death, but also because of its resemblance to our living body. The corpse, then, reminds us that death is not elsewhere, but it exists within us, in our own time. Faced with the abjection of the corpse, we often feel nauseous and vomit. This is our reaction while trying to expel the abjection within. At this moment, the subject has to abandon a part of himself to maintain stability.

Maurizio Cattelan, Bidibidobidiboo, 1996, Taxidermied squirrel, ceramic, Formica, wood, paint, steel, 45 × 60 × 48 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Bidibidobidiboo, 1996, Taxidermied squirrel, ceramic, Formica, wood, paint, steel, 45 × 60 × 48 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

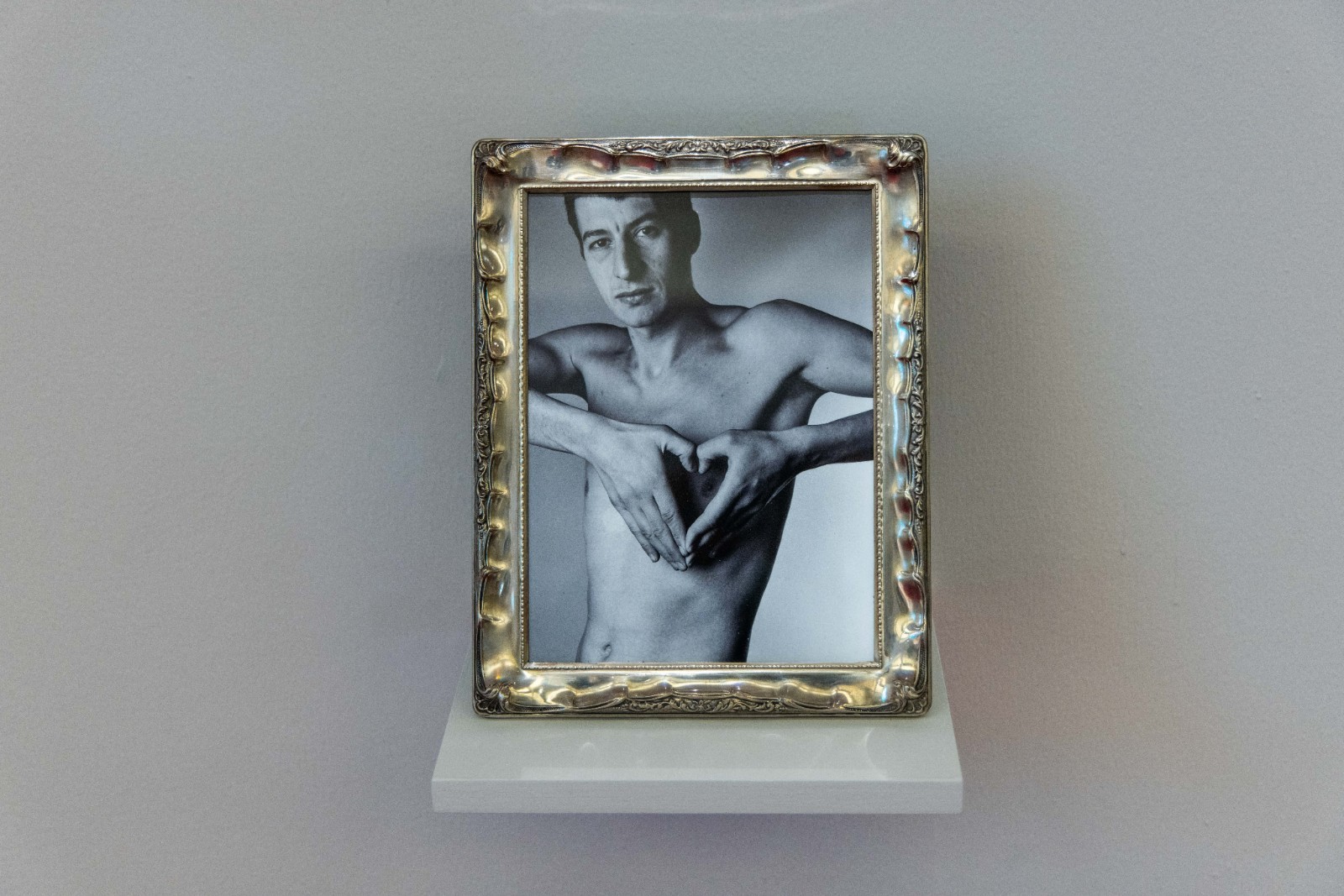

Maurizio Cattelan, Lessico Familiare, 1989, Black and white photograph and silver frame, 19.7 × 15.2 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Lessico Familiare, 1989, Black and white photograph and silver frame, 19.7 × 15.2 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

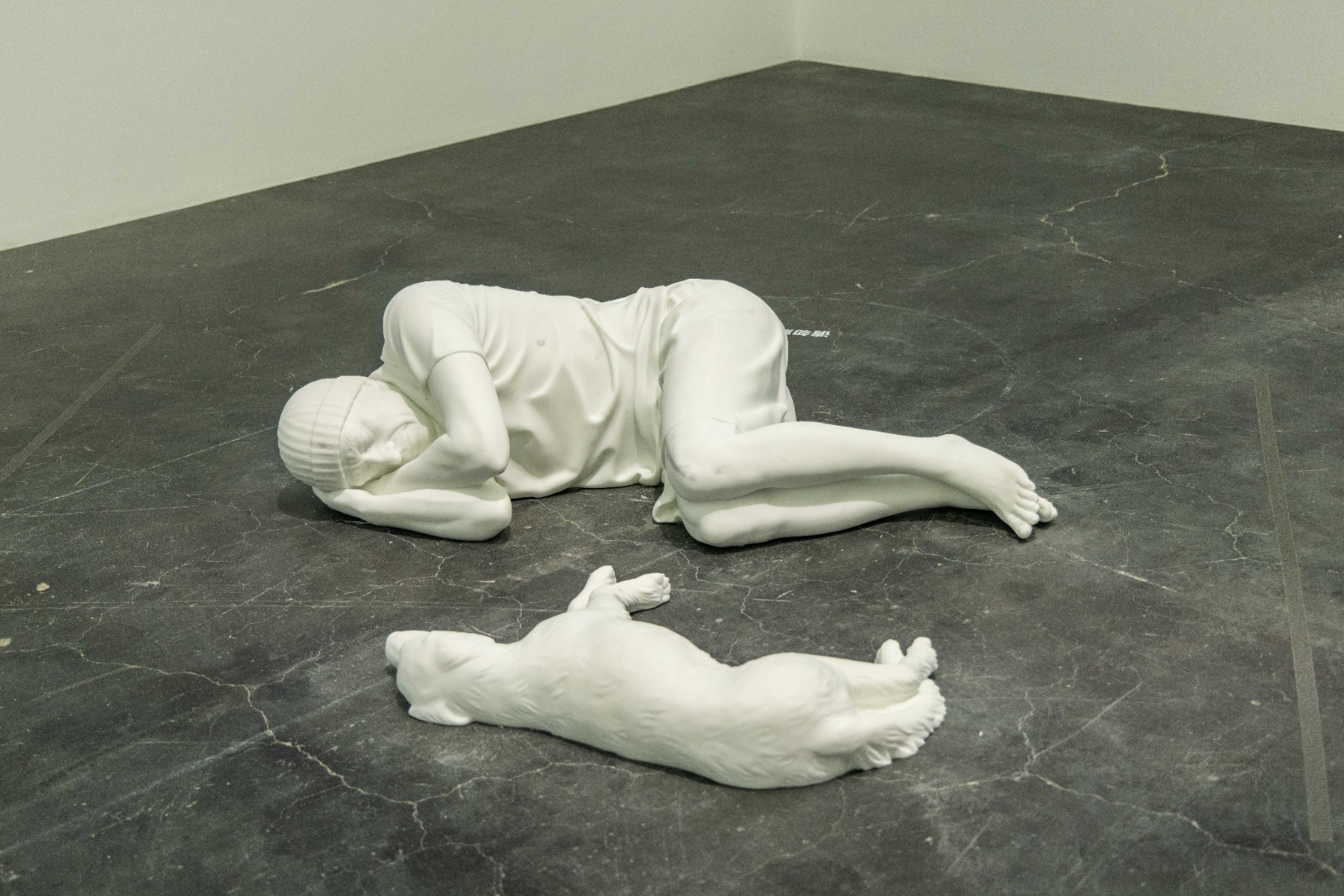

It’s hard to believe, however, that someone would actually vomit at Cattelan’s squirrel, and similarly, in a death-oriented work like We (2010) and Breath (2021), abjection is hardly true. Unlike artists who directly use or imitate blood, excrement, and bodily fluids, Cattelan is always careful not to actually trigger abjection. In this way, he maintains the character of the avant-garde, not to completely break the symbolic order and create a new one (an idea that is already impossible), but to reveal the fact that the order is in crisis. In his work, abjection is not intuitive, but is presented as a metaphor. This is amply demonstrated in his early work Lessico Familiare (1989), where Cattelan places his naked self in a typical middle-class family photo frame, an image that is directly reminiscent of the typical abjection in popular opinion of the era, AIDS-threatened gay person and the gesture of covering his nipples makes the image less aggressive. Next to Bidibidobidiboo and Lessico Familiare, there is a wall painting called Father, which almost directly expresses the role of the patriarchal law in the process of the subject moving from the imaginary world to the symbolic world.

Maurizio Cattelan, Father, 2021, Mural, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Father, 2021, Mural, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1997, Rectangular hole and pile of removed earth, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1997, Rectangular hole and pile of removed earth, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, No, 2021, Silicone rubber, natural hair, clothing, boots, paper bag, 101 × 41 × 43 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, No, 2021, Silicone rubber, natural hair, clothing, boots, paper bag, 101 × 41 × 43 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

For the collective, death is a taboo subject on most occasions. At its most extreme, the bourgeois kitsch, which modernists such as Greenberg denounced, manifested as an absolute affirmation of existence and the denial and obscurity of facts such as faeces and death. Cattelan satirizes this vulgarity with the metaphor of abjection, an excavated tomb Untitled (1997) that draws our attention to the earth—a rarity under the floor in a contemporary architectural space like UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. According to Heidegger, the relationship between humans and animals is linked to the inner conflict between the world and earth. This conflict is the key to the art work and it makes the originally closed earth open to the world. The tomb then becomes an existential allegory for art, which reveals the relationship between human beings and their own existence and death, that is, human beings are a kind of “being-for-death.” The corpse is a metaphor for the grave, the corpse that is not there ready for burial is our corpse, and this work is only available for emotional effects when we perceive the death that is inscribed within ourselves and it triggers a little bit of abjection. Another satire of vulgarity is shown in No (2021), the kneeling man in a suit with a paper bag on his head (let’s call it a man), has become a symbol of the mental health issues of the subject in the context of today’s capitalism—the subject refuses on the one hand to acknowledge the castration by the symbolic order, and the fate of death; on the other hand, in the blindness caused by denial the subject bears the real trauma.

Maurizio Cattelan, We, 2010, Wood, fiberglass, polyurethane rubber, fabric, 68 × 148 x 79 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, We, 2010, Wood, fiberglass, polyurethane rubber, fabric, 68 × 148 x 79 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Breath, 2021, Carrara marble, Human figure: 40 × 78 × 131 cm; dog: 30 × 65 × 40 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Breath, 2021, Carrara marble, Human figure: 40 × 78 × 131 cm; dog: 30 × 65 × 40 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Criticism: Irony in the Face of Difficulty

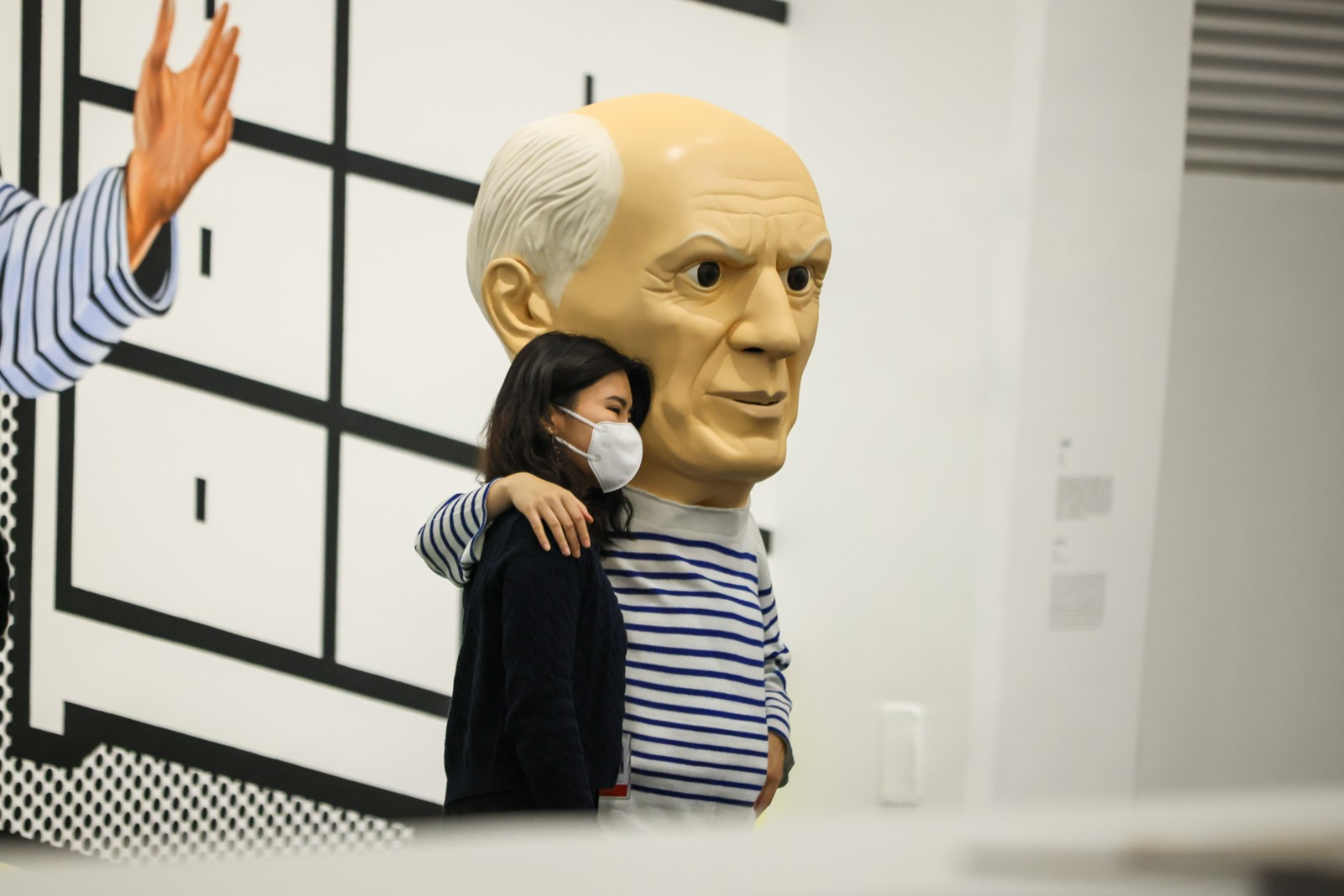

Cattelan’s “bad boy” reputation derives from his critical attitude, which has both an aesthetic and a political dimensions—a strict distinction between the two dimensions is inherently impossible in contemporary art. In Cattelan’s works, continuing the vulgar topic, we can easily turn from the psychoanalysis of the subject to the criticism of politics and power, the most typical of which is the criticism of the symbolic order in the art world. Cattelan, who is often regarded as a Duchamp-esque artist with his ironic expression, and Comedian (2019) was not absent from the exhibition. Also, UCCA Center for Contemporary Art provided a detailed schedule of performance work Untitled (1998) that Cattelan pokes at commercializing, global systems of art production as a mascot performer dressed up as Picasso at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Cattelan continues his critique of popular culture, the “American” popular culture that has lost its revolutionary nature, which continues to produce vulgarity and expands into the space of the museum. The vulgar ensures the sustainable reproduction of capitalism by implanting the ideology of capitalism into the structure of desire, and what is placed in the position of the object of people’s desire, whether it is a banana or a Picasso mascot, is only a placeholder destined to be replaced.

Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian, 2019, banana, duct tape, dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian, 2019, banana, duct tape, dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1998, Performance, polyester resin, paint, fabric, leather, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1998, Performance, polyester resin, paint, fabric, leather, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

In addition to the Duchamp-esque rebellion, Cattelan’s irony also represents a relational aesthetic community vision that constructs new principles of community through the redistribution of visible and sensible objects through works of art, a political/aesthetic community distinct from modernism. Instead, it focuses on microscopic, concrete individual relationships and experiences. Cattelan has always been good at crossing boundaries, not only from the constraints of art history and the market system, but also from the Italian world he lives in. The pope who was hit by a meteorite, Hitler kneeling in prayer, and the golden toilet named “America” are all expressing his dissatisfaction with various existing communities.

However in the space of this exhibition, unfortunately we have found a further reduction in the critique of art. A humble attitude is generally adopted by museums, not only in regard to the ability to change the world, but also in regard to the uniqueness of objects. This is partly for practical reasons: in order to survive, art institutions today are best aligned with the existing “culture.” Watching a banana in the exhibit hall, we were not sure what would have happened if we stepped forward and ate it; while watching a Picasso mascot roaming the exhibit hall, we wondered whether the performance should be viewed as a mockery of the commercialization of MoMA, or it is still a mockery of commercialization in UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. At the same time, the derivatives such as tote bags, calendars and scarves sold in stores outside the galleries have no allusion to ridicule the commercialization of art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Working is a bad job, 1993/2021, Sponsored content on LED screen, 400 × 700 cm. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Working is a bad job (1993/2021) that amply embodies this paradox, with scrolling advertisement for luxury goods, coffee machines (all sponsors of the exhibition) and UCCA itself on an LED screen. In the latter, the male star rejects coffee from a fast food company, instead riding a motorcycle back to his high-end residence to use the coffee machine. While it’s not hard to understand the bantering attitude, the advertising screen fits into the exhibition space with almost no difficulty, especially for viewers familiar with the UCCA exhibition’s long list of sponsors and “strategic partners.” Audiences in Beijing have long been familiar with the commercialization of art museums and the artistic development of high-end shopping malls, and when art museums have achieved harmony with business, when commercial sponsors have naturally regarded the humour in works targeting them as propaganda, can banters, ironies and criticisms in the title Working is a bad job still be established? What we need to ask is whether it can generate a more concrete critique when words such as “996” and “l(fā)ying down” occupy our public space?

Maurizio Cattelan, Zhang San, 2021, Clothing, boots, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Maurizio Cattelan, Zhang San, 2021, Clothing, boots, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Ultimately, we are back again with Hegel’s assertion of the end of history, and the “Last Judgment” is the moment of this end. According to Alexandre Kojève's logic, at this point the “capitalized man” disappears, while humans and animals are still alive, with no more wars, revolutions and philosophy (and no progress exists), and what remains is art, love and games (and maybe consumption). For UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, the political dimension in Cattelan’s work is indigestible, which partly explains the words “intimate connection” and “private artistic dialogue” in the preface to the exhibition. This indigestion finally condensed into the most local work in the entire exhibition, Zhang San (2021). This homeless simulacrum was abruptly placed on the red carpet and made silent, at the end of the completion of “The Last Judgment,” it becomes a naked life in a small fantasy community.

Text by Luo Yifei, translated by Sue Wang/CAFA ART INFO

Image Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

About the exhibition

Dates: 2021.11.20 - 2022.2.20

Venue: UCCA Great Hall