With the end of the exhibition “Kindness Expresses Truth and Love” in Washington D.C. featuring sculptor Liu Shiming’s more than 60 works which represent his artistic pursuit, CAFA ART INFO specially interviewed with Jiete Li, an art history researcher and curator based in Washington D.C.

Jiete Li worked as a curatorial researcher at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. for two years. As one of few Asian employees at this national-level museum, she participated in the curation of international, large-scale exhibitions such as “Female Photographers of the 20th Century” and “The Life of Animals in Japanese Art” which was a collaboration with the Japanese government. Currently, she works at the National Portrait Gallery, preparing the retrospective exhibitions of two Asian American female artists: Hung Liu and Maya Lin. Both exhibitions will provide rare opportunities to showcase the brilliant achievements of Asian artists at a national museum, which will travel around the United States to multiple venues.

Based on her multicultural background and experience in several top national museums in the U.S., the conversation started with Liu Shiming and the humanistic spirit behind his works and the acceptance of American spectators regarding Liu’s sculpture. In addition, it further developed into the topic concerning the status of the introduction to Chinese and Asian-based artists in the U.S.

CAFA ART INFO: Hello Jiete. I would like to start with a general question. After viewing this exhibition, what is your overall feeling? How do you understand his sculpture language?

Jiete Li: This exhibition touched me a lot. In Western art historical discourses, Chinese art in the second half of the 20th century generally falls into two categories: one that is critical to Chinese politics; while the other is loyal to and serves the political system. For instance, socialist realism indicates the western understanding of the mainstream Chinese art in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. However, in such a Western discourse, human, as a crucial part in art creation is neglected. How do those authentic, ordinary people live? Do they enjoy their lives? Where do the joy and vitality of their lives come from?

Neither of Liu Shiming’s works make obvious political criticism, nor are they identified as socialist realism, so it has not yet entered the mainstream of Western art criticism. Instead, his art shares me with the everyday life of ordinary people in the era of crazy changes in political society.

Another point that impressed me was the purity of Liu Shiming. He created more than 2000 works in his life. His concentrated on small people in society and paid attention to pure beauty in life, such as the mother holding her child by a station and the intelligentsia pulling the noddle car. It seems that he never considered his art’s influence on politics or society. He has not thought about how to change politics through art or how to realize a relatively grand narrative of art history. It inspires us to reflect if such purity and the respect and care to ordinary people are worth entering a grandiose historical narrative.

CAFA ART INFO: Liu Shiming developed his techniques from the experience of artifact study at the National Museum of China, and he defined it as the “Chinese Method”. He applied this technique to the motifs and topics of ordinary Chinese people’s daily life. His works stand a path toward a local mode of Chinese sculpture that diverged from the ideas and forms of Western sculpture, which presents a Chinese “modernity” at that time. Regarding “modernity”, I learned that you have been working on art history and curatorial research in U.S. for a long time, I am curious how do you understand his “Chinese Method” in a western perspective?

Jiete Li: During my years of curating exhibitions in the States, I often encounter expressions similar to “Chinese methods;” usually the word “methods” is preceded by a country’s name, say “Japanese methods,” “Korean methods”—trying to claim the “Japaneseness” or “Koreanness” in their art. Also when the Western art world started to study African American art or women’s art, there were debates around what the “blackness” about African American art was or what the “femininity” about women’s art was. All these questions were justifications by underrepresented/minority groups within an imperialist, post-modern system and reinforce the biased system. From a curatorial perspective, questions like what the essence of Chinese culture or aesthetics is, are deeply tied to nationalism and power dynamics between countries in a post-imperialist era, and I don’t think Chinese artists need to justify or claim how “Chinese” they are in front of Western audience. Western audience shouldn’t expect that either.

From Liu Shiming’s perspective, I understand why he used “Chinese method” to explain the techniques and style of his art. It is an ambitious term—tying his art to 5000 years of Chinese art history, and yet this ambition grew from the invaluable historical artifacts presented in front of him for seven years at the National Museum of China. Though copying from masters’ pieces was the way of learning about art in dynastic China (especially for painting and calligraphy), and yet not many artists could get to do so; Liu got this rare opportunity and used it well.

From a curator’s perspective, instead of “Chinese method,” I prefer to use the word “folk” to describe Liu’s art. Though he studied at the Beiping Fine Arts School and the Central Academy of Fine Arts for six years, his style isn’t academic. In terms of content, his art doesn’t talk about grandiose historical narratives (say big historical events or heroes recorded in our history books); stylistically, his art feels close to an aesthetics appreciated by “ordinary people” in the “ordinary world” (using Professor Hongmei’s curatorial language): there is something crude, unfinished, child-like (or naive), simple and innocent about his art.

CAFA ART INFO: Do you think that when Mr. Liu Shiming’s works are placed in the current social and artistic environment in the Western context, is there any possibility of “modernity” that can be continuously tapped?

Jiete Li: For sure. One aspect of modernity in his artistic language is a natural incorporation of the Western into the traditionally Chinese. He studied Western academic classicism and Rodin’s language and concept of modern sculpture at school for 6 years. This Western influence—reflected in a sincere yet bold exploration of the human body (for example his nudes) and the ability to portray physical resemblance—always lingers in artworks, even after he started pursing “Chinese methods.”

Another modern aspect of his art is that he witnessed massive economic and social transformations in China and well captured the staggering social change in his art. For example, his work Residential Building places a group of people chatting in front of a modern apartment building. Liu seems to critically think about what modernity or economic development means to ordinary people’s life: apartment buildings separate us and make us lonelier, and the only way to connect is to get out of the building and gather around in an open, public space—a space similar to a siheyuan courtyard in old Beijing. I see Liu’s nostalgia of the old way of living in this piece.

CAFA ART INFO: Curator Hongmei chose the notion of “humanist spirit” as the clue and theme of this exhibition. In your perspective, how do you connect this idea to Liu’s sculptures? What does “humanist spirit” mean to an artist or art historian in West?

Jiete Li: Liu Shiming lays his gaze on ordinary people—a woman who sells apples or a man who pushes a cart full of noodles—people whom we often neglect or even sometimes look down upon in real life. Then Liu creates joyful, humorous, dignified portraiture for them, and presentsthem in front of us to make us curious of these people’s lives and get to learn more about their stories. In the end, these ordinary people are us; their emotions—joy, agony, and confusion among others—are our emotions and our ways of living as well. Using ordinary people to convey a more universal meaning of life is the humanism of Liu’s art.

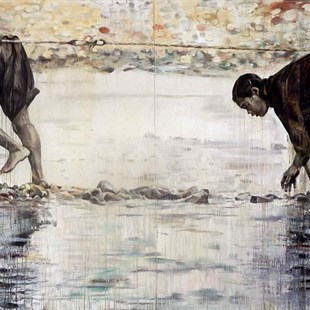

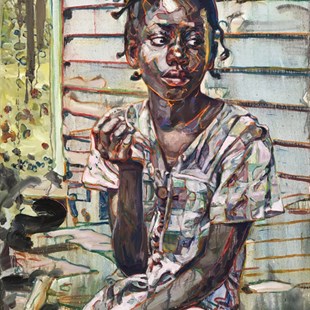

I think in the West the understanding of humanism is similar and also well treasured. For example, currently I am working on a retrospective of Chinese American female painter Hung Liu; the show will be open in May, 2021 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Hung Liu at first painted mainly Chinese or Chinese American subjects, but in the recent decades, she started painting African Americans, Irish Americans, and Mexican Americans among others. However, Hung Liu’s significant status in the American art world is not because she paints subject matters beyond her own cultural background or ethnicity, but because her art explores human rights and universal humanity underlying historically difficult moments. She often paints the weak, exploited, and enslaved—prostitutes, refugees, soldiers, laborers, and prisoners, among others. Hung Liu using her compassion and sensibility masterly portrays hope and humanity breaking through the dark moments in human history.

Liu Shiming and Hung Liu grew up in China around the same time. They both studied at CAFA and experienced China’s massive socio-political changes. This may be the reason why both of them have this kind of humanism—an eye for vulnerability and a compassion for the ordinary.

CAFA ART INFO: In your opinion, what is the significance and value in terms of holding Liu Shiming’s sculptural exhibitions in New York and Washington D.C.?

Jiete Li: New York is the center of the international art world. There are a good number of Chinese students pursuing the arts there, scholars whose specialty is Chinese art, international tourists, and immigrants from all over the world, so I think it’s easier for New York audience to understand and appreciate Liu Shiming’s art.

However, DC is different. DC is a place filled with national museums serving, to some extent, political agendas of the country and trying to include art into the grand historical narrative. So far I wouldn’t say Asian art plays a significant role in DC’s artistic landscape, especially in the recent decade when the MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements push women, African Americans, and Latinos to the foreground while leaving Asians behind. Also these aren’t many Asian art experts in DC, so it may be hard for local audience to understand Liu’s art or locate it within a larger art historical discourse. However, I think it’s extremely worthwhile for people to see his art in DC. In a city obsessed with politics, it’s refreshing to see something not overly political from a country often understood from a political sense in the West. I hope that this exhibition could be a seed of Chinese art and culture in local audience’s mind. If Liu’s art could get them interested in modern and contemporary Chinese art and culture, I believe more China- or Asia-related exhibitions could happen in the near future.

CAFA ART INFO: From your background as a curator in national museums, what do you think of the status of the introduction and research on Asian and Chinese art in the United States? In the future, what are the possibilities for mutual exchange and dialogue in art and culture field between U.S. and Chinese?

Jiete Li: In Washington D.C. besides Freer Sackler which is the National Museum of Asian Art, there is another museum dedicated to Asians—the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC). APAC is now in the process of fundraising 25million in order to have a permanent gallery space in D.C. to showcase the achievements of Asian Americans. This endeavor is inspired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Latino Center which already existed for a few years. If the fundraising succeeds, then for the first time, in the nation’s capital, there will be a permanent space dedicated to Asians. This would be an extremely exciting opportunity and platform to promote Asian cultures and the arts.

Besides these two D.C. organizations solely dedicated to Asians, other museums have also been trying to incorporate Asian voices gradually. The National Gallery of Art is curating an exhibition on 20th-century women photographers, and Chinese photographer Niu Weiyu (some objects borrowed from the National Art Museum of China) will be shown. This will be the first time the National Gallery of Art borrowing modern and contemporary Chinese artworks from China.

Also, at the National Portrait Gallery, Hung Liu’s retrospective, including 52 large-scale paintings, will be open in May, 2021. I’m also working on a Maya Lin’s retrospective. Maya Lin is Lin Huiyin’s niece, and Maya is most known in the West for her Vietnam War Memorial. Both exhibitions are exciting and rare opportunities to showcase the brilliant achievements of Asian women.

There are exciting shows on Asia coming up in D.C., and yet I think it depends more on how Asians advocate for their rights in the United States. If they could voice more and engage in political discourse more actively, then more Asians could be shown in the nation’s capital. What if Andrew Yang wins the presidential election in 2020? (I’m not trying to predict the result of the presidential campaign, but it’s fun to just imagine a future where Yang becomes the first Asian president of the US.) Then the racial landscape and political discourse on race in DC might transform dramatically. Let’s await the exciting political change in 2020!

Interview conducted by Emily Weimeng Zhou

Interviewee: Jiete Li

Edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Exhibition View: Qi Siyang

Artwork Photos Provided by the exhibition organizer

Other Photos Provided by the interviewee

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and National Portrait Gallery