In 1929, Xu Guangping gave birth to the only son of Lu Xun in Shanghai and he was named Haiying which meant “a baby born in Shanghai.” For Haiying’s education, Lu Xun let him develop freely as he had written in his earlier essay entitled “How to Be a Father.” Zhou Haiying showed an interest in photography and radio from childhood, and with the support of his family, he became a radio expert and photographer. As a descendant of a celebrity, Zhou Haiying has received a great deal of attention since he was a child, but he always kept a low profile. Over the 70 years that he has worked within photography, Zhou Haiying has never published any photographs. It was not until 2008, when his eldest son Zhou Lingfei intended to organize a photography exhibition for his father’s 80th birthday that his photos were made public.

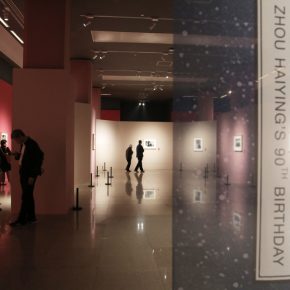

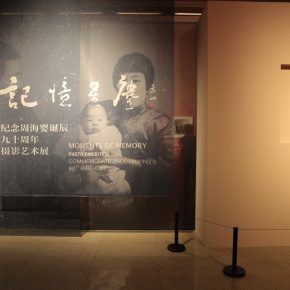

Recently, “Moments of Memory: Photo Exhibition to Commemorate Zhou Haiying’s 90th Birthday” was held at the National Art Museum of China. The exhibition featured more than 100 representative photographs during the 70 years of Zhou Haiying’s art career, and it was divided into five chapters, providing an opportunity for us to review Mr. Zhou Haiying’s photographic art.

Zhou Haiying became attached to photography only 20 days after he was born as Lu Xun organised a photo session of him. On the occasion of a hundred days of his birth, Lu Xun’s family went to a renowned photo studio in Shanghai to take a group photo. Each year on his birthday, they took a picture to commemorate the day. Starting from the family memories, the first chapter showcases the photos of Zhou Haiying and his parents, the private photos of the elders and the family photos taken by Zhou Haiying.

Zhou Haiying’s first contact with a camera was from his mother’s friend Cai Yongshang. In October 1936, Lu Xun passed away, thus Cai invited Xu Guangping along with 8-year-old Zhou Haiying to recuperate in Guangzhou. Cai had a small Contax camera from the German company ZEISS. Zhou Haiying was very curious and he pressed the shutter several times with the permission of Cai. In 1943, Zhou Haiying borrowed a box camera from his mother’s friend again and officially began his experience in photography. In 1944, Zhou Haiying used his own pocket money and lucky money (money given to children as a lunar New Year gift) to buy his first camera in a second-hand camera store, and he continued to maintain his love for photography thereafter.

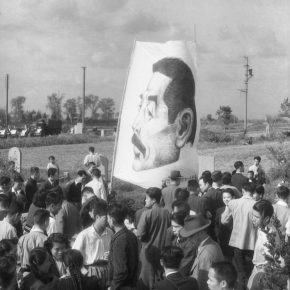

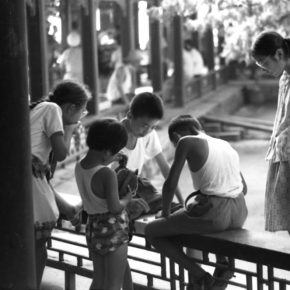

Zhou Haiying took tens of thousands of negatives over his lifetime. According to his memorabilia, these photos can be roughly edited into four chapters. From 1936 through to the end of 1948, Zhou Haiying and his mother had been living in Shanghai. During this period, he purchased cameras several times and then moved to the Northeast via Hong Kong at the end of 1948. In 1949, Zhou Haiying was preparing to go to the Soviet Union to study, thus he returned to Shanghai to “seek his original cultivation.” He recorded the urban life and various states of citizens in Shanghai from the late 1930s through to the late 1940s. Following the first chapter above, photos of Shanghai recorded by his cameras constituted the second chapter of the exhibition. At the end of 1948, Zhou Haiying followed his mother and a group of democrats to North China from Hong Kong. Due to confidentiality, there were no arrangements for photojournalists. Zhou Haiying’s cameras were used to record this period of history, which also constitutes the third chapter of the exhibition: “Northeast: Red Journey.” After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Zhou Haiying followed his mother Xu Guangping to settle in Beijing where he went to school, worked, married and had children. At the same time, he continued to maintain his hobby in photography. Through his lens, “the People’s Liberation Army entered the city”, the life of college students and the daily life of citizens, like frames of classical time, images constitute the fourth chapter of the exhibition.

The last chapter of the exhibition focuses on Lu Xun through Zhou Haiying’s lens, which showcases Shaoxing, the hometown of Lu Xun. This does not just work as a life documentary of Zhou Haiying as a photographer, but also the father and son’s affection in Zhou Haiying’s heart. In 1929, Shanghai was still influenced by overseas control and the living environment was terrible. Lu Xun and Xu Guangping had no plans to raise children. Because of the failure of contraception, Xu Guangping was pregnant and this unexpected child brought joy to Lu Xun, who was nearly 50 at that time. Although he lived with Lu Xun for only 7 years, Zhou Haiying can remember his father offering him a lot of care and love. On October 19, 1936, Lu Xun passed away. On the following day, the testament published by Ta Kung Pao in Tianjin, including one provision: “When the boy grows up, if he has no talent, he should find a small business to make a living, he must not be a vain writer or artist.” This was a recognition of endless love from the father Lu Xun who could not be around during the growing years of his son Haiying.

The exhibition was unveiled at the National Art Museum of China, which introduces the perspective of Zhou Haiying, through which we view Lu Xun’s private images, a loving mother, a beloved family and a lovely child; the living conditions of the middle class as well as civilians in the alleys, pictures recorded democrats travelling from Hong Kong to the Northeastern Liberated Area, including a large number of photos of Fu Jen University and Peking University. Through his lens, from the unknown citizens to the wise men, from the older generation to the fashionable youths, from suffering to new life, from scenes of town streets to the cities, etc., they are so abundant that audiences might feel overwhelmed. Zhou Haiying’s photographic works showcases a broad social picture, from family to society, from individual to collective, they are so inclusive that they are also interspersed scenes and details of previous political events. His photographs truly reflect the social ecology of that era and the living environment of people. This is an excellent representation of the photographic culture in modern Chinese history which is also of great value for the study of modern history of China. These are the moments of memory left by Zhou Haiying, which also provide us with a view on the modern history of China. Some scholars have commented on his photography: “The only photography that can be mentioned in the same breath with this of the same period is the great work that French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson took in China from 1948 to 1949.” Some critic even commented: “Zhou Haiying used cameras to continue Lu Xun’s career: observing the ‘post-Lu Xun era.’” This is undoubtedly the highest evaluation and affirmation on this low-profile photographer.

“Moments of Memory: Photo Exhibition to Commemorate Zhou Haiying’s 90th Birthday” is one of the “Donation and Collection Series Exhibitions of the National Art Museum of China” in 2019, Mr. Zhou Haiying’s family donated a group of Zhou Haiying photographs and documentary to the National Art Museum of China to fill the space of the famous Chinese photographers in the 20th century, which also comprehensively constructs and contributes to the rich and representative collections of the National Art Museum of China. The exhibition will remain on view until March 17.

Text and photo by Yang Zhonghui/CAFA ART INFO

Translated and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy of the National Art Museum of China