By Li Xu, Curator

Surrealism and Pop Art

Born in 1971 in Guiyang, Zhong Shan began painting in his teenage years, and in the autumn of 1991 enrolled at the Central Academy of Fine Arts to study mural painting. His education at the Central Academy took place just after the 85 New Wave Movement had drawn to a close. Although this vigorous avant-garde art movement has already passed, for most of the artists who developed outstanding practices after the movement, that period was a golden era, during which these artists, who later became recognized internationally, matured their artistic language and style. With a foundation of diligent and industrious study over two years, Zhong Shan was capable of fusing his developing painting technique to his thematic interests, with his imaginative approach reaching the canvas with many freely composed dream-like images. His artistic expression was enlightened by the modernist Surrealist masters, including Salvador Dali and Rene Magritte, but he was also noticeably influenced by Academy painting faculty members Cao Li and Tang Hui. After graduation, Zhong Shan continued as a professional artist; from 1994 to 1999 he experimented in genres ranging from Surrealism to Pop Art, employing diverse artistic languages that combined the fantastic and grotesque in conjunction with cartoons, computers, cyborg insects, marionettes, ancient warriors, temple ruins, and township characters...... This diversity of imagery juxtaposes the macro and the micro, couples archaeology with science fiction, overlaps the imaginary and the real, and contrasts the everyday with the exceptional.

Silk and Numbers

Zhong Shan’s experience living in Shanghai from 1999 to 2008 contributed to innovations in his practice that extended beyond traditional easel paintings, initiated with works that integrated diverse materials onto transparent light boxes. Later, he turned to a conceptually based non-figurative process that incorporated Arabic numerals onto silk. Initially, Zhong Shan densely stacked tiny numbers into realistic outlines of surreal images. Eventually he abandoned completely the representative image, replacing it with the pure rendering of the numbers 0123456789 in a continuous stream to form a repeating numerical cycle that filled long silk scrolls. With such an extraordinary effort of repetitive labor, this Zen-like practice gained distinction for its expressive technique, and the work was selected for major exhibitions including Metaphysics 2003: Shanghai Abstract Art Exhibition (Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, 2003) and Prayer Beads and Brush Strokes (Beijing Tokyo Art Projects, Beijing, 2003). The original abstract numbers, in their final synthesis on silk as the material carrier, are suspended in a vertical hanging that depicts an invisible concept in a tangible physical mass, with the elusiveness of time stacked as a physically evident memory. Furthermore, the transparency of the silk allows light to engage in the overall visual effect of the work, and foreshadows for the viewers significant insights that will inform Zhong Shan’s future projects.

Double Images

In 2004, Zhong Shan began a seven year project on a series of paintings titled “Double Images.” After his return to Beijing in 2008, this series became a primary focus for his work. The images used in his paintings are in bilateral symmetry and bidirectional coordination, while the pictorial narratives are developed through progressive mutation and variation. The juxtaposition of the two images' form and content is complementary and intertextual, reflecting both symbiotic and parallel connections, while still establishing a relationship of paradoxical conflict. The “Double Images” series represents a return for Zhong Shan to oil canvas paintings and realistic representation. The “Double Images” are highly symbolic, despite the absence of clearly identifiable distinct forms; the series discloses a profound aspect of reality hidden in the seemingly ambiguous content. The works use the relationships between people and objects as a starting point, with the further focus of the series being a consideration of complexities below the surface and a reversal of causality. Through the persistent exploration of the series, Zhong Shan gradually comprehends that what he creates in his visual imagery should transcend the parallel surfaces and juxtaposition of relationships possible in two-dimensional space and be transformed absolutely by superimposition into three-dimensionality. He set about on a new program before the “Double Images” series is finished and his artistic expression has since expanded to an unexpected, new level of space-time experimentation.

Separation of Vision

After 2010, due to his inexhaustible curiosity, Zhong Shan again transformed his creative approach; he began to introduce a distinct multi-layering to his works, with images produced on both sides of a translucent material comprising a single work. Some of the layered figurative forms and landscape elements correlate, while other have obvious dislocations; selected elements are strongly highlighted, while others have dreamlike characteristics that initially recede from the foreground only to later re-emerge. Things only suggested are contrasted with forms boldly outlined, and collectively this reinforces a sense of strangeness and mystery, deliberately creating unexpected encounters. The rules governing these formal variations change with specific contents. Unique concepts require specific materials. Hence, Zhong Shan has reintroduced silk; combining realistic images with experimental use of a material, which leads to a series of stunning visual experiences. The relationships between emptiness and form, light and shade, front and back, identical and reverse are, in the agile hands of Zhong Shan, all turned into viscous, loose, or translucent strokes, with the light transmitting from the back or coming from the front, eventually becoming intangible visual and psychological experiences beyond words. The ancient organic fiber of silk is revived in Zhong Shan’s artistic creations with this traditional cultural material obtaining a new unexpected vitality in his works.

During this period, we can clearly see in graphic information of Zhong Shan’s works the integration of diverse sources. They include collective memories from student days, famous city landmark buildings, gas-mask clad pedestrians in smog, ordinary scenes of déjà vu appearance, floating human bodies, and portraits of Che Guevara, Marc Riboud, and Cui Jian: a complex range of image resources with diverse cultural allusions. Through these unique arrangements and combinations Zhong Shan’s special individual interests and thinking in recent years is revealed.

In work produced recently over two years Zhong Shan reveals a fascination with a form of “fragmented voice” as found in common social media. A superimposition of images results in constant ambiguities, with floating elements shifting through different works; vitamin-capsule-like figures filter out unnecessary contents in one scene, and manifest themselves in the form of WeChat dialogues to highlight significant information in others. Although everything within the painting seems to relate to a visual ontological methodology, the focus is completely subjective and individual. Zhong Shan states that none of his latest works can be completely controlled; therefore, his process of creation continues to be exciting, and is accompanied by unfolding discovery, and the inexplicable does matter in the visual arts, precisely because it allows the viewer a broader understanding and experience of space.

Alternative Ending

Even though we have a high volume of daily visual experiences, specific environments can function with extremely limited elements. The emergence of these elements in the moment of encounter with the artwork is purely a matter of chance, rather than resulting from an overly rational process. In fact, daily life provides a visual experience with a variety of hidden details in shape, color, contrast, and rhythm; if we could carry out a kind of soulful archaeology of these experiences, we would bedazzled by what is to be found in these precious discoveries. In a cognitive process, we often cannot avoid the habit to categorize and summarize, and tend to not consciously and rationally seek the relevance and meaning behind the image. Nevertheless, the essence of the world is naturally complex, while the human development of things is prone to running in the opposite direction against reasoning. Perhaps the best way to understand our familiar but absurd world is by admitting to the existence of confusion and uncertainty. Though confronting and uncritically accepting such uncertain visual experiences causes discomfort or a sense of unfamiliarity, by taking a new look at the surrounding world, we may acquire an awakened consciousness and a renewed sense of existence.

Some film directors when releasing DVDs or Blue-ray Discs of their films provide the option for alternative endings in the playback menu. This is possible because two or more outcomes were shot originally, while cinema audiences are only able to see one ending officially approved by the producer. With these new media formats, directors can now more fully express their multiple creative intents, and in doing so leave viewers with more options. I chose Alternative Ending as the theme for Zhong Shan’s exhibition of new works precisely because the works from the outset were not intended to have a single reading. Actually, no particular set of steps are necessarily the correct way or should lead to a sole interpretation; the means of appreciation vary from person to person, and it is always an individualistic process that holds optional, alternative, open, and uncertain paths.

27 February 2016, Shanghai

By Pi Li

Zhong Shan was my best friend in college. At the?Central Academy of Fine Arts, he was in the Mural Painting Department and I was enrolled in the Art History Department. He was a couple years older and had entered college a year earlier than me. We came to know each other through his teacher, Tang Hui, who had been recruited as a faculty member in the Mural Painting Department just after graduating from the Academy. Tang Hui’s and my parents were colleagues and old friends, while Zhong Shan’s uncle Cao Li was also a faculty member in the Mural Painting Department. Both of our families hoped that Tang Hui would help look after us, and it is for this reason that Zhong Shan and I became good friends. I always thought that Zhong Shan and I had many similarities; for example, each of us had family members that were doctors. As a result, we both attached importance to cleanliness, which in the cramped dormitories of the period with students mostly from the outlying regions, was exceedingly rare. At that time, the students enrolled at the Academy had either graduated from the affiliated middle school of the Academy or taken a series of entrance exams over five or six years to gain entrance. Regardless, students from either track would have left their parents by the age of 15 or 16, and had formed scary health habits that were more than a little worrying. As my major, I had to study the decidedly unpopular area of art history at college. While Zhong Shan, who was considered a troubled youth and was always getting into fights, came to the Academy after it was estimated he didn’t have the interest needed to pass the entrance exams to a regular university. I studied at a horrible middle school where often an orderly class would be rushed by other students and fights ensued; being detained after class was a commonplace occurrence. Zhong Shan also spent his adolescence embroiled in fighting and learning to draw because of the huge challenges faced in getting admitted to regular university. These common experiences forged our friendship. I felt very lonely when I first entered college, and Zhong Shan was like a big brother to me: naturally we would band together to carry out assorted misdeeds, like drawing fake film tickets on the weekend in order to sneak into the Longfu Temple cinema for the all-night movies. (Many other stories are omitted here…)

Born in the 1970s, our generation led a life that seemed more dull and uneventful, with fewer ups and downs. During the dynamic period of the 1980s, we were considered just kids; when the fine arts scene started to boom, we had only just graduated from college. When the market economy emerged, we were still looking for direction in our careers. Thus, our generation seemed to always be lagging behind; forty years passed in a flash for us. Our lives had less the victorious face to face confrontation with destiny’s plan and were rather more like the humble man prodded along by time’s pushing hands, which appeared soft and gentle, but would strike you when your attention wondered, and caused you to lose your center of gravity. Zhong Shan’s path developed as an artist, as an earnest artist, was not one that led to overnight recognition. With his quiet, contended disposition and individual honesty, he always seemed to be roaming outside of the established art circle. After a few mixed years following graduation from college in the early 1990s, he took a job in the decorating industry for a year before resigning to become a professional painter. Later, he moved to Shanghai for an extended period before returning to Beijing again at the beginning of the century. Even after so many years, Zhong Shan in my mind has remained the same; he has always adhered to an evolutionary creative process in his art. When the market was booming, his works sold well, but he terminated his exhibition contract with the gallery and turned to a new process, scripting numbers onto long scrolls of silk. Even when the market contracted, he still engaged in creating works of completely different styles. As his old friend and a critic, I have witnessed the changes in his approach and written articles on his many varied series of work.

After he graduated from college, Zhong Shan developed a unique surrealist style, one that combined the puppets and games of his childhood with social reality. This style draws on influences from his two most important teachers, Cao Li and Tang Hui. Cao Li and Zhong Shan were both born in Guiyang. Cao Li became known in the art world in the 1980s for his uncanny but idyllic pastoral style of work. I always felt that the artists from the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau had an oddly sly and crafty temperament. Time moves slow there and the folklore stories of ghosts foster in the artists a natural affinity with primitivism and surrealism. The artistic style of Tang Hui is also based in a form of surrealism. Yet, his style differs from Cao Li in that he uses animation and cartoons combined with depictions of history, revolution, and futurism to create a sense of coldness and indifference in contrast to the mellowness and rich colors of Cao Li’s work. Thus, we can see that the earlier artistic style of Zhong Shan was deeply influenced by these two teachers; he possessed the ability to deconstruct deep space as in Tang Hui’s paintings, while producing works with warmth, like a glowing light in the darkness.

As an artist, Zhong Shan is fortunate to have left Beijing for Shanghai, as it allowed him to quickly advance to new approaches. Although he had already developed diverse styles, and established his own artistic language and a set of methods, the commercial atmosphere of Shanghai served as a new stimulus for him psychologically and visually. Surrealism gradually disappeared from his work, yet as a kind of sublimated temperament, it had instilled a sensitivity to time and space. The urban environment gradually became the central focus of his work during this period, but with particular interest in the psychological relationships of the urban individual to time and space. In many works, the artist employed a “mirroring” technique to express a change from the gaze to the trance, which I believe also reflected the experience of Zhong Shan living as an “outsider” in Shanghai. He has referred to these mirroring as “Double Images,” not to indicate a relationship in language but rather a co-existent time-space relationship. During this same period, he developed a performance-like painting process, done year in and year out, which involved repeatedly imprinting the numbers 0 through 9 on silk scrolls tens of meters in length. These works are referred to as “recording time” by the artist. This ritualist writing provided a means to claim time and still the mind, while the long and winding silk scrolls themselves occupy the time and space of the exhibition hall, embodying neither proximity nor distance. These two forms of creation, which might appear on first view to be different, in fact reflect the same issue of the individual’s sole and mind in the process of urbanization.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Zhong Shan returned to Beijing. After nearly a decade, people finally saw these new groups of work. The artist had begun to abandon the canvas and draw on transparent silk. Thus, the “Double Images” originally mirrored on one side were now transformed into images unfolding through a positive/negative space; the transparent silk enabled the mirrored images to overlap while still producing a sense of separation between them. This approach creates a myriad of parallels in the exhibition hall, while compressing time and space. Though each image is realistic in its rendering, the relationships between the different images are surreal. In terms of the thematic content, the artist shifted from general observations on human existence and the capturing of urban scenes from years earlier to an examination of his own existence, dreams, and experiences. For Zhong Shan, evident throughout the exhibition, there is a continuing interest in confronting the issue of space, namely the problem of how paintings exist in space. He combines two stylistic forms in Shanghai, yet bravely abandons those identifiable symbols to claim a unique personal form. The content of each screen is rich and flexible, while the existence of the painting breaks away from the wall and integrates with the space, becoming an object in the gallery. Here, multiple images are compressed in space, creating a unique visual experience.

Over the past years, I have felt an engagement with the changes I see in Zhong Shan’s process; I admire his courage and I’m amazed by his growth. In today’s China, we often feel that we are out of touch with our times; the education we received taught us the taste, techniques, and persistence of the last century, but the rapid development and changes occurring around us in this era make us feel helpless and restricted. Some artists try to conceal these difficulties by constantly chasing a new horizon. Other artists, like Zhong Shan, instead turn inward to examine themselves and their life experience, and then transfer this experience into new forms of vision and space, yet behind these forms is still a kind of nervousness and uneasiness. Zhong Shan’s works and what they represent are consistent with his state of mind. He is an introverted man and often absent-minded; yet whether in conversation with us, in the city he lives in, or in the circle of contemporary artists, Zhong Shan is present at the same time making you feel he is an outsider. It seems that the development of art in our era has lost a united direction; with its accelerated pace, every artist can rise to fame on WeChat for a fleeting moment. Acknowledging this reality, one is able to understand the floating images in the exhibition space: they are the momentary suspension, trance, and departure from real life in our era. What the artist can do is to open his heart and wait calmly. Art, in fact, means waiting: one creates a work with one’s hands and waits for others to be surprised and to understand. This response might arrive, or possibly not. But most likely, if it does come, one no longer cares about it. So now, as you enter the exhibition hall, you enter the artist’s awaiting. And at this moment, as his contemporary, colleague, and friend, and because we share the same experience of this tumultuous period, he and I feel the same uneasiness.

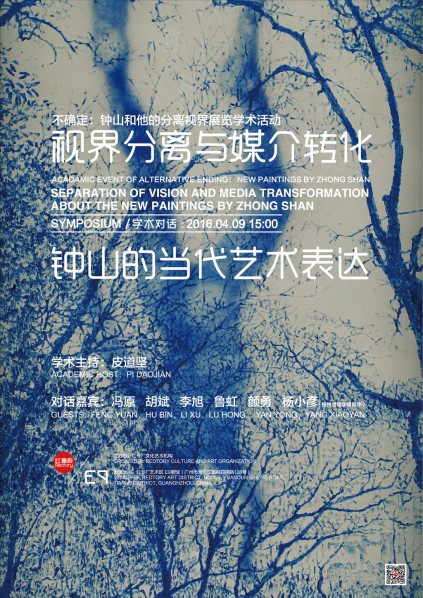

About the exhibition

Academic Host: Pi Daojian

Curator: Li Xu

Organizer: Redtory Art and Culture Organization

Academic Schedule:

2016.4.9

3:00PM

Academic Dialogue: Separation of Vision and Media Transformation

- About the New Paintings by Zhong Shan

Academic Host: Pi Daojian

Guests: Feng Yuan, Hu Bin, Li Xu, Lu Hong, Yan Yong, Yang Xiaoyan

4:30PM

Opening Ceremony

Duration: 2016.4.9 - 2016.6.18

Venue: E9 Gallery, Redtory (No. 128 Yuancun Siheng Road, Tianhe District, Guangzhou, China

Courtesy of the artist and Redtory, for further information please visit contact pr.officer@redtory.com.cn or visit www.redtory.com.cn.