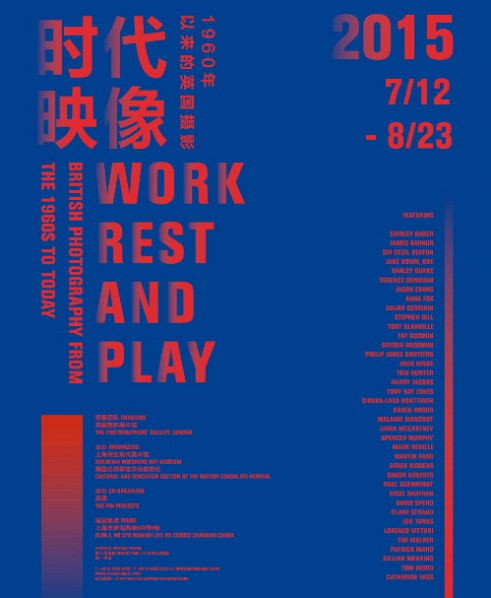

Arranged chronologically the exhibition explores British society through changing national characteristics, attitudes and activities over the last five decades. Multiculturalism, consumerism, political protest, post-industrialisation, national traditions, the class system and everyday life all emerge under the broader themes of Work, Rest and Play.

1960s

In the 1960s, Britain went through numerous social and cultural changes. The infamous ‘Swinging Sixties’ saw London established as a centre for music, fashion and a flourishing British art scene. Photographers were interested in capturing the world around them as it changed, documenting events of social and political significance, while others used photography to create work of a more personal nature. Editorial photography thrived through commercial magazines, as did professional studio portraiture evidencing the growing cult of celebrity within popular culture.

Terence Donovan’s work emphasised a newly found playfulness that took fashion photography out of the studio and into the street. Similarly James Barnor’s striking images of models of African heritage used London as an exciting backdrop, using the city to express new freedoms and emphasize a cosmopolitan lifestyle.

Cecil Beaton applied all his skills of visual seduction to produce new icons for this new era. Portraits of pop-stars, fashion models and artists did not merely capture the sitters’ personality, but also confirmed their status within the cultural scene. Linda McCartney, married to Paul McCartney of the music group The Beatles, was able to merge the public and private to produce celebrity images that were simultaneously family snapshots. This new intimacy had a great appeal for viewers, offering a sense of authenticity.

In his ‘Only in England’ series, Tony Ray-Jones took on the role of social anthropologist to pinpoint particular foibles of the British. While John Hinde’s brightly coloured photographic postcards, celebrated working-class British leisure pursuits.

1970s

In the 1970s, Britain was going through a period of economic recession, resulting in high unemployment and disillusionment with political institutions and other establishment figures. In response, many photographers became more politically conscious and socially engaged, documenting declining industries and their communal effects – choosing to work outside the traditional structures of portraiture, fashion and photojournalism.

Photographers like Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen and Shirley Baker recorded working-class families and marginalised communities in parts of England where traditional life was under threat, whilst photographers such as Vanley Burke focussed on the ethnic minorities striving for equal rights. All of these photographers were committed greatly to their subjects, offering a complex rather than clichéd view of their environment.

Philip Jones Griffiths’ images capture the seemingly absurd but deadly serious political events that dominated Northern Ireland during the 1970s. Similarly Patrick Ward’s images observe the various forms of classed-based rituals and regalia often mocking theoutdated social systems in ‘Wish You Were Here: The English at Play’.

In the editorial world, Jane Bown’s long career established her as one of the most consistent portrait photographers of the era. As a female photographer in a predominantly male arena, Bown’s contribution offered a striking blend of the iconic and the informal. While Harry Jacobs’ portraits of first, second and third-generation Caribbean immigrants taken in his high street portrait studio offered a unique record of a community undergoing massive social and cultural change.

1980s

With the rise of City culture and the fall of the Trade Unions in the 1980s, British society was defined by a new economy. The Falklands War, Miners Strike, high unemployment rates coupled with a new government headed by Britain’s first female Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the birth of the modern British dance and drug culture offered photographers a wealth of possible subject matters.

The documentary style that had defined the 1970s was now replaced by satire and colour documentary photography that provided a new vision of a nation. Martin Parr – a colour photo pioneer – challenged the ‘mythology of Britishness’ with his satirical images of every day life. Similarly Anna Fox’s images provided a parody by documenting new forms of work and office culture– triggered partly by the introduction of the computer to office-–based work?– her images depict a culture of alienation, superficiality and excess. Tom Wood’s street scenes of his hometown Liverpool offer empathetic and affirmative documents of lived moments of working– class men and women.

In contrast to the bright and colourful depictions of everyday behaviours, and informed by a sense of ecological crisis and activism present in 1980s England, Fay Godwin’s quiet, black and white images of the British countryside and coast, reflect the complex relationships between man and nature.

Photography also took a conceptual turn in the 1980s. Interested in post–structuralism, gender–inequality and psychoanalytical theory, many photographers turned towards the medium as it seemed to be freer and more versatile than sculpture or painting. With her ‘Gentlemen’ series shot in exclusive all–male clubs, Karen Knorr addresses the seemingly fixed class and gender relations dominating Britain in the 80s.

Subcultures and alternative lifestyles allowed people to step sideways from conventional roles and imagine themselves differently. Derek Ridgers portraits celebrate these eccentric styles of nightclub goers that express their wish to stand out.

1990s

The 1990s was a decade of contradictions, on the one side political promises were made to restore Victorian values; on the other side social liberalism flourished. The result was a dramatic change in how Britons viewed homosexuality, individualism and almost every ancient institution; the Royal Family, the church, the political system and marriage were all subject to scrutiny. Identity became partly a matter of choice and Britons participated enthusiastically in the opportunity to explore different persona. British photography diversified as photographers found and celebrated the freedom to experiment.

While Toby Glanville’s series of portraits of workers reflects on the importance of traditional British trades and crafts. Jason Evans’ influential fashion photos show black models dressed as upper-class dandies, parading on real urban streets; the antithesis of the image of black youths as gangsters. These images create an alternate world into which viewers might choose to project themselves.

Britpop, Cool Britannia and the Girl Power phenomenon dominated popular culture of the1990s. Portraying the young fans of the Spice Girls— the influential all female pop group one of whose members Victoria became the wife of David Beckham—posing as their stars, Clare Strand’s images contrast the vulnerable, preteen fans with the stereotyped view of femininity embodied by their role models.

Paul Seawright’s series Sectarian Murders revisits the sites of religious motivated murders that took place in the 1970s in Belfast close to where Seawright grew up. These images accompanied by the newspaper reports document the banal location where the murders occurred and challenge the viewers’ perception and the production of the history of the conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland.

Like Seawright, Tom Hunter revisits in Life and Death in Hackney sites of news stories. In melancholic images influenced by compositions of Old Master paintings and situated in urban wastelands, Hunter spins narratives of a disenchanted generation.

The New Century

Since the turn of the century, Britain has seen much radical social and economic transformation. New technologies and the explosion of self-expression on social media revolutionized how people communicate and how they express themselves. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, international terrorism, the financial crisis, globalization, were all important topics that defined this new era.

Photography in Britain has been a complex endeavour over the past 15 years. Contemporary photographers have moved around the country observing and collecting new narratives and exploring the boundaries between the still and moving image. Their views are often enigmatic, involving conceptual elements and telling contradictory stories ambiguously situated between fiction and fact.

Stephen Gill’s playful and poetic series “Talking to Ants’ features insects and objects being placed into the body of the camera to produce unique layered images; encapsulated in the film emulsion, they become part of the photographic process, evoking dream states or an “ant’s eye-view”. Shifting perspectives and dream sequences also play an important role in Tim Walker’s fashion fantasies. Here models enact fairy tale scenarios, the pleasurable escapism of the images seems often more important than the clothes themselves.

Consumer culture and its related aesthetics is depicted in Nigel Shafran’s series of ‘Supermarket Checkouts’, these luminous still life images are in some sense improvised portraits of the customers who bought these items. Many contemporary British photographs provide a twist on the traditional genres of landscape, portraiture, still life and history painting, drawing links between photography and a broader history of art. Julian Germain’s group portraits of school children reflect upon educational conventions and the school portrait format as highlighting social divisions. Offering us an opportunity to scrutinize the faces of sportspeople, actors and authors who often seem absorbed in their own private thoughts, Spencer Murphy’s classical portraits combine pictorial formality with intimacy.

The grand landscapes of Simon Roberts’ series ‘We English’ return to the subject matter of Tony Ray-Jones and Patrick Ward –the English at leisure. His photographs have a painterly quality as they show people enjoying their leisure activities within the British countryside; whilst the idea of the British Empire and how Britishness may be perceived in the remaining overseas territories is explored in Jon Tonks’ photographs.

Questioning the way that photographic documents are usually circulated to an outside audience for some kind of profit, Mark Neville came up with a solution to the issue that allows the pictures to “belong” more fully to the people depicted in them. When he completed a 2004 residency photographing the community of the former ship-building town in Port Glasgow, Scotland, eight thousand copies of the book Neville created to document the community were delivered only to the eight thousand families who lived there, no further copies of the publication were made available beyond this community.

Also reflecting upon the idea of communal ownership, David Spero’s ‘Churches’ expose unlikely places, repurposed and reused as places of worship by the burgeoning communities of evangelical Christians who have come to London from all over the world.

In the past decade, British artists using photography have begun to expand their horizons, exploring the terrain of sculpture, installation, painting and performance as well as video and film. Lorenzo Vitturi’s vibrant still life’s and temporary structures put photography into dialogue with other art forms. Vitturi made the work in response to the lively environment of his local street market in East London.

Video and Animation

Emerging with the first portable video cameras in the 1960s and 1970s, video art has been defined in part by what it is not; not television, not cinema and not still photography. Embracing this medium, photographic artists oftenturn to video when aspects of time and movement can add to the impact of their work.

Gillian Wearing’s hour-long video piece ‘Sixty Minute Silence’ shows twenty-six actors posing as male and female police officers standing or sitting, as if poised for a group photograph. By trying to sit completely still the work is playing on the long exposure times of 19th century photographic portraiture. If Wearing’s video is a study at the edge of stillness, Melanie Manchot’s ‘Tracer’ is a celebration of reckless movement. Manchot’s piece shows 10 traceurs or parkour runners, climbing, leaping and flipping their way along the course of the Great North Run.

Time actually loses its direction in Catherine Yass’ video work Lighthouse. Filmed in a downward spiral from a helicopter, boat and underwater, Yass plays with feelings of disorientation set against the purpose of lighthouses to signal danger, points of shallow water, whirling currents and extreme tidal pull.

Finally Dryden Goodwin combines photographs of passengers on London public transport with animated drawings. Part of a larger exploration of the relationship between photography and drawing, these are meditations on the way we look at strangers.

Documenting and observing the changing realities of the British nation, the thirty-eight artists and photographers here express strong social engagement, a love of the ordinary, an intense curiosity and the constant need to record. Through the artists’ special perspectives, the exhibition demonstrates that along with music and fashion, photography has been a field in which Britain has made both a complex and accomplished contribution.

Also on display is The World in London, a major public art project initiated by The Photographers’ Gallery in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympic and Paralympic Games. The project presents 204 photographic portraits, from both established and emerging talents, of 204 Londoners, each originating from one of the nations competing at the Games. It is a celebration of photographic portraiture as an artistic form of expression as well as the city’s rich cultural diversity.

In conjunction with the exhibition, talks, children’s workshops and university lectures will be presented together. The exhibition will run through August 23, 2015.

About the exhibition

Dates: Jul 12, 2015 - Aug 23, 2015

Opening: Jul 12, 2015, Sunday

Venue: Minsheng Art Museum

Artists: Shirley Baker, James Barnor, Cecil Beaton, Jane Bown, Vanley Burke, Terence Donovan, Jason Evans, Anna Fox, Julian Germain, Stephen Gill, Toby Glanville, Fay Godwin, Dryden Goodwin, John Hinde, Tom Hunter, Harry Jacobs, Philip Jones Griffiths, Karen Knorr, Sirkka-Lisa Konttinen, Melanie Manchot, Linda McCartney, Spencer Murphy, Mark Neville, Martin Parr, Tony Ray Jones, Derek Ridgers, Simon Roberts, Paul Seawright, Nigel Shafran, David Spero, Clare Strand, Jon Tonks, Lorenzo Vitturi, Tim Walker, Patrick Ward, Gillian Wearing, Tom Wood, Catherine Yass

Courtesy of the artists and Minsheng Art Museum, for further information please visit www.minshengart.com.