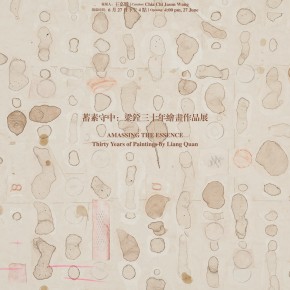

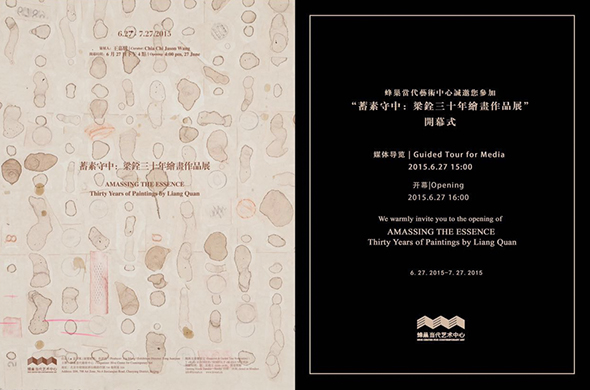

Hive Center for Contemporary Art opened Amassing the Essence: Thirty Years of Paintings by Liang Quan on 27th June, 2015, the exhibition showcases his most important works since 1982 in its 5 exhibition halls, reviewing systematically the concept of his artistic practice, and exploring the method of his practice and the causes of his aesthetics. The exhibition is curated by Chia Chi Jason Wang, a renowned scholar from Taiwan, and it will last till the 27th July.

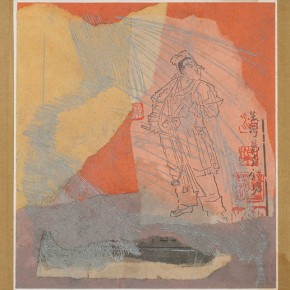

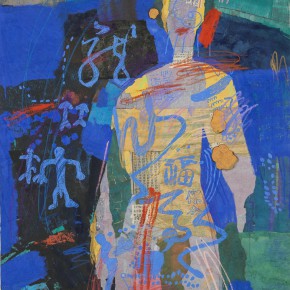

Liang Quan always hoped to revive the spirit of artistic refinement in the Chinese cultural tradition, pursuing profundity within the everyday and seeking to glimpse the innate beauty of nature. From 1985 to 2000, he had a period of “manipulating a riot of colors.” and based on the stylistic traits of these works, we can call it his “heavy color period.” Liang Quan’s works in this period are full of chance collages of heterogeneous objects, such as prints or rubbings serving as cultural or symbolic signifiers, which actually mix in a variety of cultural signifiers reflecting the phenomenal world, unavoidably project or allude to his own implicit feelings and thoughts about family, society, nation, history and tradition. Starting in 2000 he incorporated tea into his paintings, subtly encompassing his own philosophical perspective and life aesthetics within his works. He no longer focused on such phenomena in his art. Instead, he started putting in order his own states of mind and attitudes toward life. This was the true beginning of his abstract art. Returning from surface form to essence, returning from confusion and disorder to a calm, untroubled state, Liang Quan had found creative belonging, after coming to understand his destiny.

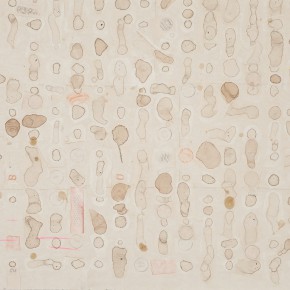

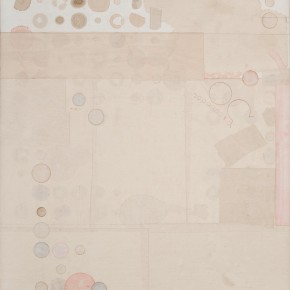

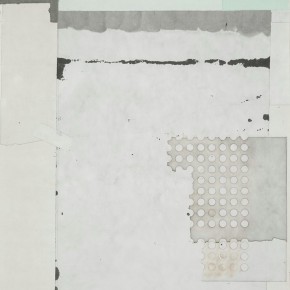

Using different variations in the color of tea, as well as collages of absorbed ink and pigment, Liang Quan composed uniformly delicate abstract images. This mode of formative expression is reminiscent of the ancient Chinese aesthetics of porcelain, and the subtle color gradations that occur in tea tasting, when the hues of the tea blend with the soft tones of the porcelain cup. This small-scale aesthetic of the cadence of color is purely East Asian, indeed unique to China. Forming a bridge with this traditional, distinctive aesthetic history through his art is Liang Quan’s most important contribution to contemporary Chinese ink painting and abstract art – a topic worthy of further exploration.

Returning to the purity of the materials themselves, he retained tearing, dyeing and pasting as his fundamental techniques, but to these he added the act of cutting. Meanwhile, Liang Quan began to consciously pursue a color aesthetic of plainness. This he achieved in a number of ways – by making his pigments light or thin, or by using the natural purity of a single color of ink. He achieved intricacy through simplicity, with a complex texture of wrinkles and innumerable colors underneath a base of paper made of orderly layers that were seemingly cut or torn evenly. Charged with feeling, the works were achieved by a decidedly non-mechanistic sequence of duplication. Paintings composed in this manner appear at first blush to be minimalist. Viewed more closely, they seem subdued. Carefully perused, they are imbued with lush variation.

Artist StatementBy Liang Quan

The philosophy of Zen Buddhism has been weakly reflected in modern fine arts. Enthusiasm and indifference are all illusionary. When things disappear into non-existence, this is a status of Zen. I have been calling myself a disciple of Zen but I did not prove it in my works until recent years. When I look back at the works of mine over the past ten years, I find old memories so flimsy that they seem unreal. Those colorful structures and youthful passion look as if they are not mine. I have moved on to another stage of my life, giving up the careful “fullness” in painting. Instead, “emptiness” (sunata) is the core of my pursuit. It is a peaceful change in my life and I am calm to it. I even do not have any special feeling about it. To present “emptiness” in paintings seems to be easy but also difficult at the same time. “Emptiness” means something else other than that in the literati paintings, in which “emptiness” is used to express “fullness.” However, what should be done if one simply wants to express “emptiness” itself? It is definitely not without a stroke. But if one paints, where should one put a stroke? As a stroke is done, “emptiness” will be absolutely gone at once. There should not be any difference between drawing a stroke or not. Otherwise, the whole meaning will become an illusion.

I had been worried about the resolution of “emptiness” for a pretty long period of time. Time flew as I was cudgeling my brain and gradually changing my style. I started thinking deeply about Buddhism. This condition persisted until one day when I took a walk along a river bank. I saw a wilderness where grasses were growing disorderly. I stared at them for a while and found that they looked like something as well as nothing. Suddenly, some ideas came to my mind. Although these are flickering ideas, I was sure about the general picture as a whole. I did not need to bother about the details. The bank was adorned with green. Willows and new grasses were dancing in the breeze. These grasses were swaying gently. They looked so fresh, so fragile, and so trivial. Being trivial, the grasses were charming. At least, they were growing for themselves. I looked at a slim Semen Plantaginis in the mass. I could not see its blades and spikes clearly from a distance. I stared at it for a half minute and then moved to other plants. Just then, I could no longer identify that Semen Plataginis in the mass. The world is delicate and real but everything seems so trivial.

As a matter of fact, the world does not have to be meaningful. However, it is definitely delicate and real. . .

The actual effects are counteracted by the delicate and fine details. As a result, the whole picture is empty. This may be a possible method to realize “emptiness.” “Fullness” is always expressed by “emptiness” in the literati paintings. Using the same logic in a reverse manner, “emptiness” can be expressed by “fullness” if proper way is employed. The little grasses are standing naturally in the wilderness. They do not have to be the models or rules for other grasses. Their existence in the crowded space does not bear any great significance. This is the original sense of the world: The trivial parts exist independently and there are not so many rules.

To realize “emptiness” with lots of details, those calm, irregular, and silent lines should not be too eye-catching. Then they will make themselves natural in the painting, expressing the peace of Zen.

On one hand, under a certain circumstance, fortuitous details are connected by a certain mechanism. This connection is generally considered as abstract. However, when the relationships between the lines are handled in a sophisticated way, they will become real substance that maintains balance. If a holistic mastery of these irregular and silent lines is achieved, these lines will form relationships in spatial structure. These relationships are the key to the maintenance of balance in painting. These relationships could be dynamic. When those finite and irregular details are put together, it is easy to leave imagination to people. In fact, this is an illusion of memory. Impression of infinity is produced by the simple repetition.

On the other hand, however, this approach to “emptiness” is not explicit. It would be better that it gives the impression that the artist has not done anything. There are rules for processing a piece of art. Nevertheless, as I explained earlier, there are not so many rules in the world. People will not follow the thoughts of the artist. The stronger the artist emphasizes the ideas and themes of his art works, the greater he manifests spiritual despotism. As a matter of fact, responses to art works spring spontaneously from individuals. Artists can only introduce their thoughts to their audience. They can never impose their thoughts on their audience.

Thirdly, the modern industrial society of superfluous and mass production will need a supplementary that is simple and minimal in the pursuit of spirituality. Shan Neng, a Buddhist master in South Song Dynasty said, “People are afraid of the heat of summer but I enjoy long summer days. As the breeze comes from the south, it cools down the temperature in the room.” When most people are chasing after the fad of being outstanding and gorgeous, it is a responsible attitude towards the world, the history and oneself to insist on a simple style: To stay with silence, anonymity, and tranquility; and to remind oneself frequently not to worry about the chaotic world and fame.

In short, the expression of “emptiness” is achieved by the “l(fā)ack of rules” of the art work and the “l(fā)ack of doing” of the artist. Here, I come to a satisfactory cycle of my soul searching. In front of this endless and mysterious world, I do not struggle. I only submit myself to it.

These trivial lines seem meaningless when separated. However, once they are put together without rules, the painting is completed. The “richness” and “emptiness” come to an agreement. Triviality is not different from splendor. To achieve “emptiness” has profoundly changed my attitude towards life. Personally, I consider it more important than the exploration of fine art. Actually both of them are just the two sides of the same coin. In these days, I have learnt to take a walk outdoors everyday as the elderly in the park on river bank. I do some physical exercises to my waist and legs that are not yet rigid but sure to be so in the near future. Sometimes, I sit under trees quietly, thinking about nothing. I am calm because I have already given up deep thoughts and I am just sitting there. My mind is sometimes empty and sometimes full of endless ideas. These ideas come and go like wind, having nothing to do with one another. They are only broken pieces of memory from the past. The appearance and disappearance of these disordered broken memories produce an image of disordered and chaotic numbers. In one second, I may think of one day long long ago. Nothing happened on that day and the memory concerned disappears soon before the arrival of the memory of another day. It is worthy to mention that the memories of these two days are not successive. It is not the matter of “tomorrow” or “yesterday.” I do not know the order of these two days and how long is the time between them. I cannot find out the relation between them. As for the second day, nothing happened as well.

My art works is moving on in this endless chaos but I feel good about it. I am waiting, thinking, thinking, and waiting. I am anxious and I cannot think of any question. Perhaps all questions are resolved already, or perhaps there is no question at all. I am pleased in this irregular, delicate, and real world. I content myself with tranquility and the lack of ambitious plan: I do nothing.

Courtesy of the artist and Hive Center for Contemporary Art, for further information please visit www.hiveart.cn.