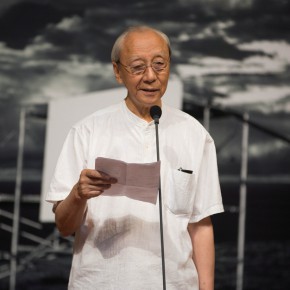

By Fan Di'an, President of CAFA and Curator of the exhibition

The arrival of the age of image is posing increasingly urgent and the real challenges to contemporary painting-something not only China, but the world on the whole, has to grapple with. A loyal painter, therefore, is expected to be one who not only sticks to his dream and belief but also explores new possibilities in pictorial thinking and methodology in art production. In the past several years, Liu Shangying has been making conscientious efforts in this respect.

Over the last consecutive years Liu has made several trips to Tibet during the summer vacation. Travelling alone across the uninhabited areas in north Tibet or visiting Ali by himself for long hours along Mount Kallash, he looked for a place in nature where his soul could settle in peace and get purified, more than an art production site that was home to his free mind. After two years’ trek, he finally settled down by Lake Manasarovar.

Lake Manasarovar, also called “Holy Lake”, lies peacefully amid the snow mountains on the plateau, with Kangrinboqe, also known as “sacred mountain”, situated by its side, casting its reflection on the calm waters. In this ancient and peaceful land, what has been there for millions of years unfolds into eternity and a mystery of nature. As a Buddhist pilgrimage site, every year it receives Buddhists from Tibet, India and Nepal. Around the mountain and the lake, they trek and pray, adding to the pious atmosphere that envelopes the area in silence. It is all about the silence of nature, for at an altitude of 4600m there is absolute peace and one cannot hear anything but his own breath and heart beat; it is also about solemnity, for the sacred sense of nature, beautiful nature, holds people in awe who come up. The landscape therefore disciplines all visitors spiritually, brings them into harmony with nature, and leads them to reevaluate life. In that place, Liu appreciated and experienced nature, but more importantly, he was a trekker and explorer devoted to art: he spread large canvases by Lake Manasarovar, ready to translate what he felt and experienced on the trips to Tibet into art vocabulary. He was fully exposed to pure nature, but he would rather not do a still landscape painting. In front of the scenery, “I fixed the canvas by the lake at the same time each day. I would spend much of the time staring at something, usually two or three hours, so that my observation could penetrate and I could put myself at the absolute mercy of instinct. At that moment my self and art seemed to have ceased to exist.” It echoes “sitting in oblivion”, a classical term in literary creation in ancient China. Embraced in nature, sitting in front of a blank canvas, one gets fully immersed in perceptual intuition and unrestricted meditation. “Observation” and “meditation” were thus joined at that moment and the artist, absorbed in the enigmatic harmony, brought himself to an absolute free state to embrace a sense of “primodiality”.

Such feeling usually comes at the end of the process, and it is also a state in which one places his or her mind in “void”. “Oblivion” here refers to the removal of distractions, and in particular, the suspense of the previous experience in art. According to Husserl, to comprehend the nature of things, one has to experience “epoche” that is intended to set aside various assumptions and beliefs about a phenomenon in order to explain a phenomenon in terms of its own inherent system of meaning in “l(fā)ichtung”. It is of course impossible for a phenomenon to present itself automatically in “l(fā)ichtung”, so its revelation actually means the transcendence of all the concealments on the part of a participant who thinks and meditates, so it requires an artist to meditate about the world before him or her in order to remove all the concealment and take his or her thinking and feeling to a “void” base point, a starting point to approach all the phenomena. For Liu did not dwell on the landscape that can be captured with a camera but tried to capture the soul of the landscape that would stay on the canvas. While keeping “gazing” and “observing” nature, he found a game was on as his soul and the landscape interacted, a game between “the soul following the landscape” and “the landscape following the soul”. It became a dialogue between “the soul” and “the landscape” which finally led to the landscape in his inner world.

Sometimes Lake Manasarovar was so peaceful that one could hear nothing but the heavenly sounds of nature, but the wind from the plateau kept changing its direction, so what unfolded to Liu became a myriad of views: gale, heavy clouds, a downpour, clear vaults or a rosy sky setting off the beautiful lake… Such changing landscape made traditional painting from life almost impossible-there was also no sense in it. However, from “sitting in oblivion” to “getting activated”, he, pushed by an impromptu instinct to create, plunged himself into a state that fused the self with the landscape. This is how these works were completed. Meditating before the landscape brought him to a turning point where he was able to share the rhythm with the landscape. Then he started to paint and was almost unable to stop. He worked freely on the huge canvas and also made modifications. With the painting tool he made himself, he spread a large amount of paint on the canvas. Sometimes the canvas was placed on the ground, so he splashed and spread the paint from the four sides; sometimes the canvas was erected, so he could arrange color blocks, the composition of points, lines and the plane with the landscape in front of him becoming his reference, but more essentially, a kind of inspiration that helped to transfer his feeling from nature to the tableau, from the landscape to the painting.

His each and every painting can be viewed as the result of his journey that started from “the void”. The academic background in painting, particularly such aspects as pictorial composition, coloring and the rendering of images, proves his skill as a painter, but in the meantime it easily betrays his prior experience. By the lake, he tried to rid himself of the prior training experience, particularly the “style” born of long practice, so as to “return to zero”, in other words, to get a new starting point. His works accordingly took on new looks, including the tools, the material and ways of expression. With a departure from the conventions on indoor painting, he directed everything to the “impromptu” and “immediate” feeling, taking the most from the harmony between the rhythm of his art production and that of nature. The new pictorial structure in his paintings showed that he seemed to be following instinct and feeling while painting, but in essence, he was drawing upon his meditation. “Meditation”, the clue to his feeling, turned his thinking into emotions, therefore enabling him to make adjustments in color, including its tendency, thickness and texture. In the combination of points, lines and planes, new natural movements and abstract forms interact, highlighting both the abstract aspect of the tableau and the rich spectrum of the natural scenery.

Strictly speaking, these paintings are not about the landscape in Tibet but about the artistic conceptions or perceived settings the landscape provided. Also, the implication of “setting” goes beyond “l(fā)andscape”, as “setting” relies on the landscape, but more importantly, it comes from the self that is embraced in the landscape. This state of art creation can be analyzed on three levels. First comes the relation between “man” and “setting”. To stand aloof from the age of image, he is fully aware, an artist has to leave the hustle and bustle of the city. These journeys took him away from the noise of mundane life, so that he could reevaluate the reality of modern life, particularly the spiritual belonging. Painting, he believes, as an art form, is part of tradition, but the starting point in painting can be novel or unconventional. “Only in nature can we feel the strong pull from our inner world,” once he told us, “find the state of excitement and activate the instinct to create.” What he is looking for is therefore new experience for his physical self, and it involves a great effort in discipline. Then comes the relation between “l(fā)andscape” and “setting”. Facing the scenery that kept changing unpredictably, he had to resist the urge to capture the scene objectively and detach himself from what he saw, so as to approach the variety of landscape from a perspective that combined intellect with emotion. In this sense, what he aimed at is to turn the concrete “l(fā)andscape” into a specific “setting”, and give more implication to “setting” than the concrete “l(fā)andscape” can carry. The last deals with the relation between “mind” and “setting”, the most essential of the three. Facing the changing landscape, while looking for the one and only feeling, he had to clarify “the chaos” in the painting, that is, to take the final appearance into control. What is in contrast to the phenomenal world, according to Nietzsche, is not “the real world” but the formless and indefinite sensible world that is all about chaos. It is therefore another side of the phenomenal world and it is “unknowable”. To a painter, painting means confronting chaos. Liu, with an increased awareness of the contingent and generative aspects of this process, followed up the clue of the landscape shifted to the tableau, and connected the sentiment with the setting. With the abstract factors playing the leading role, the pictorial vocabulary was highlighted on a free and unrestricted tableau that was like a grand symphony of landscape, air and light.

For Chinese oil painters of landscape motif, there are two great assets. One is the tradition of Western landscape painting rooted in the centuries between the Renaissance period and the modernist period. Some of the characteristics of this tradition have survived to this day and become part of our cultural landscape, such as the natural aspect of the landscape, the identity of the national state and the symbolic function of religion, etc. Landscape is a vehicle for feeling, memory, as well as symbolism. Knowing quite well the experience history leaves us, Liu responds to the challenge to find something new to transfer the new ideal to experience the landscape and express such an experience, in other words, to respect in a more profound way the cultural aspect of the natural landscape. In his rendering of the sublime of nature there are discernable traces of “the grand narrative”, which explains the grandeur of “the perceived setting”, like a heroic epic. In this sense, he is incorporating his own interpretation into landscape painting. Another asset has a lot to do with the experience from Western abstract painting and abstract expressionism, which works as our historical reference for the form and rhythm of pictorial language, as well as the pictorial composition. In his painting career, Liu has learned a lot from western pictorial techniques in order to connect himself with modern visual experience in terms of pictorial language. Meanwhile, he has also benefited greatly from the concepts and techniques in traditional Chinese painting that led him to the essence of feeling and expression of nature- the fusion of the East and the West becomes the basis of his exploration in art.

“To impart more poetic flavor, void and stillness are never to be forgotten. A full knowledge of every motion comes from a still setting, and myriad visions rise from the void.” “Seeing off Master Can Liao”,a poem by Su Dongpo, not only offers a new perspective in the discussion of the relation between the mind and nature, but more importantly, it marks the shift in the pursuit of artistic conception in Chinese art since the Northern Song Dynasty. Only with an undisturbed mind can we understand every motion in nature, as is implied in this rich and meaningful poem, and only a void mind is large enough to hold the universe and give expression to it in the form of painting. Therefore, what Liu brought us from Ali are not only colorful sketches of nature but also new findings and inspirations in contemporary painting methodology.

June 2015

Painting in NatureBy Liu Shangying

When I devote myself to nature, it does not change; when I bring my paintings to nature, it remains as normal. Nature does not need to be painted or praised.

The beauty of the wilderness overwhelms me, a so-called civilized human being. Getting closer and closer to the unknown world, we seem to have everything in control. The individual self was never at the core of art in ancient times when paintings were characterized with a respect for nature. The moment human beings stepped on the moon, they lost their reverence for nature.

Painting, with tens of thousands of years’ history, is as difficult to define as human beings themselves. At this moment and in this place what is on my mind is to paint in nature, something that has no bearing on painting nature.

Ali is a vision, for it is by no means real to me. Looking so close, the boundless clouds are rolling and dancing, striking me as something rather indifferent. Painting there, we are like moths flying into the flame. Everyday at the same time I would fix the canvas there, but I would spend most of the time watching for two or three hours, I think. When gazing at the same place for a long time, I forget myself, along with art.

In order to be closer to ourselves, we have to travel far. Distance strengthens our will power, rids us of complexity and saves us from sluggishness and trivial matters. On the long treks I explored what painting really means to me. There excitement and fear followed each other. Every year I went to the same place where I find the same stones lying there undisturbed. It was so close to me, but I knew nothing about Ali, I remained as ignorant as I had been when I got there the first time.

Trying to find the tie with nature, I, in its embrace, came to find a tempo and a kind of piety that restored me to calm and peace. Then painting became a kind of labor and tilling, simple and plain, that freed me from anxiety.

About the artist

Liu Shangying, associate professor, vice-dean of the Oil Painting Department of CAFA, now teaches at Studio No. 3, Oil Painting Department, CAFA. Born in 1974 in Kunming, Yunnan, he graduated from the Middle School Affiliated to CAFA in 1995 and got a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s degree in Literature respectively in 1999 and 2004 from Studio No. 2 and Studio No. 3, Oil Painting Department, CAFA.

Liu’s paintings are concerned with nature, but he is related to nature not as a visitor or someone that experiences it but a trekker and explorer actively engaged in thinking about art. From “sitting in oblivion” in nature to “getting activated” by nature, Liu closely connects his art production with his act of painting. His paintings reveal strong artistic instinct derived from the moment and the place that helps to fuse the self into the landscape.

About the exhibition

Duration: June 16 through to June 25, 2015

Venue: The National Art Museum of China

Courtesy of the artist and the National Art Museum of China, for further information please visit www.namoc.org.