October Gallery is delighted to present the first solo show in London of Wang Huangsheng (b.1956, China). As one of the most influential figures in the art world of China, Wang’s work can be found in many international collections, including the V & A, London, Uffizi Gallery, Florence and the National Art Museum of China, Beijing. From light installations to sculpture, Wang Huangsheng works across a variety of media, but primarily uses the traditional medium of Chinese ink on paper. At a time when ink painting is enjoying renewed global attention – as evidenced by recent exhibitions at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art – the distinctive character of Wang Huangsheng’s work cuts a unique and resolutely individual path.

Familiar with the arts from a young age, Wang Huangsheng accompanied his father, a noted Literati painter and calligrapher, when he was sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976). This provided ample time to practise and absorb the time-honoured traditions of painting, calligraphy and poetry as handed down by his father. At the end of the Cultural Revolution, a time of radical change, Wang moved to Beijing, where he met with outspoken poets such as Bei Dao and the leading intellectuals of those tumultuous times. Wang sees these twin poles, of collective traditional values and contemporary modes of individual expression, as together informing his profession and practice. After further formal studies, he obtained an MA in Art History from the Nanjing Art Institute, in 1990, and his Doctorate, in 2006. A former Director of the Guangdong Museum of Art, Wang Huangsheng is currently the Director of the CAFA Art Museum, the most influential art space in China.

In Chinese thought, the poet, the painter and the calligrapher are different facets of the same practised talent – the ability to characterise reality. Words, in Chinese, are abstract pictures of the real world, so an intangible idea, such as ‘civilisation’, is constructed from two pictograms: the first meaning ‘word’ and the second ‘dawn’. Civilization, to the Chinese, is thus predicated upon the origins of writing itself. The primordial element of writing is the inky dot on the blank sheet of paper. This can be extended into two kinds of line, one vertical, the other horizontal. Further transforming these elements into diagonal lines completes the syllabary of five basic strokes from which all Chinese characters (hence all potential descriptions of the world) are generated.

The Chinese Literati artists used the same inks, brushes and basic strokes to render the still more detailed descriptions of the world that we recognise as representational paintings, the majority of which would also contain a written poem.

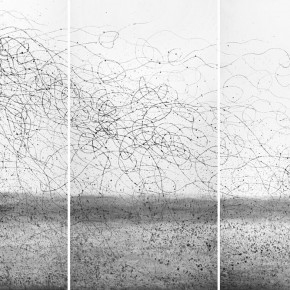

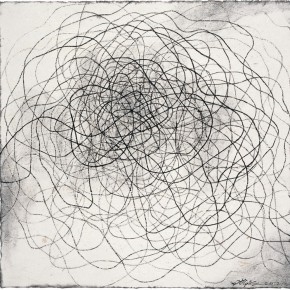

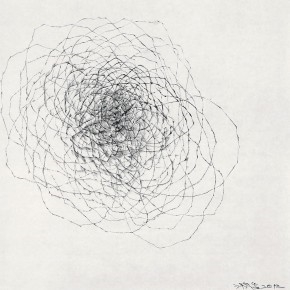

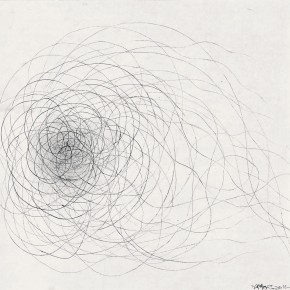

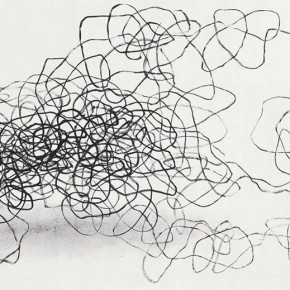

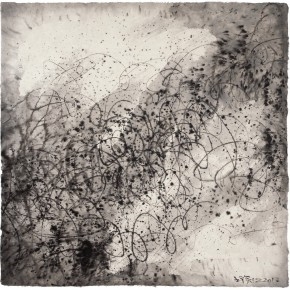

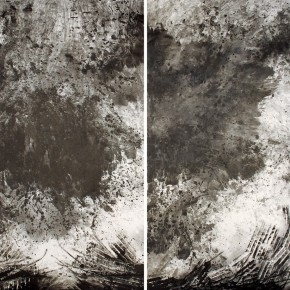

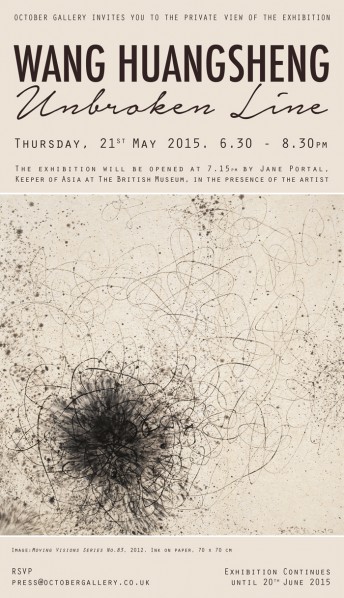

Here, in his Moving Visions Series, working primarily with a single unbroken line, Wang Huangsheng breaks beyond the fixed conventions of traditional brushstroke painting, returning in a radical manner to an ‘uncivilised’ world preceding language. The cursive line roaming the paper’s field suggests the potential of that unanimous world of nature existing just out of the reach of words. These aleatory abstractions suggest another world, one free of the boundaries limiting consciousness with discrete definitions. Wang Huangsheng’s poised brush, freed from all restraint of the conscious mind, becomes an instrument to channel the unwinding silken thread of the wider world’s immanent consciousness. Ever the poet, the artist describes that spontaneous sense of freedom expressed in these moving lines as being like that of: “a boat floating without anchor into the infinite emptiness.”

Preface: When like – minded friends arrive from faraway places – howcan we not be happy?

Founded by artists, architects and adventurers from different places, October Gallery opened, in the centre of London, in 1979, intending to test the germ of a novel idea. As advanced as the so-called ‘a(chǎn)vantgarde’ seemed to be, its absolute importance was persistently overstated in comparison to the arts of other traditions beyond the pale of the western canon. The early 20th century provided many telling examples of this self-serving tendency, as major western artists developed their modernist agendas by borrowing elements from African art to describe those African sources – their tutors, infact - as ‘primitive’. In the multicultural metropolis of London this fertile interchange between the many cultures from around the planet is everywhere apparent. Over the years we met many artists from Africa, Asia, Australia and beyond, whose practice was profoundly rooted in their own cultures and, yet, who were simultaneously alive to recent advances at the forefront of the rapidly developing lobal artistic culture. The hybrid vigour of their collective creative strategies pushed the artistic boundaries forward on a planetary scale. Since the term ‘a(chǎn)vant-garde’ itself was now associated with one particular period, and seemed only to apply to western artists,we began to refer to cutting-edge artists from around the planetas artists of the Transvangarde– that is to say, the trans-culturalavant-garde – and set out to search for others. In thirty-five years of expeditions around this extraordinary planet we met many like minded friends, discovering a network of Transvangarde artists both nearby and in faraway places.

As chance would have it, 1979 also marked the beginnings of a ‘New Spring’ in the Chinese art world, the upwelling currents of what came to be called the ‘New Wave’. Yet a decade passed before, in 1989,the gestural abstractions in oils of Xi Jianjun attracted our attention, and October Gallery gave a solo show to its first ever Chinese artist. Soon after, Xu Zhongmin’s arrival in England translated into a still closer relationship, and he became a firm favourite of the Gallery’s cultivated audience. By the end of the ‘90s, it was becoming clear that there were several divergent streams of Chinese artists: those still working within China, and those wild geese who, for a variety of reasons, had flown abroad and were establishing reputations in London, Paris, Honolulu, New York, etc. In 1997, to highlight this complex relationship between Chinese contemporary artists and the international art world, October Gallery presented an exhibition by Xu Zhongmin and Ye Yongqing. Both artists had graduated from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, but each was now forging a quite different career in London and Chongqing respectively. Structured as a stimulating dialogue between two close friends, the show was provocatively titled Between Two Places, and examined the underlying question of what constituted Chinese art at that time, probing its dependence on identity and the crucial importance ofplace.

More recently, our maturing relationship with Chinese artists has broadened to include the large-scale photographic scans of Huang Xu and the ambivalent calligraphic explorations in impas to acrylics of Tian Wei. The former has always worked from Beijing, the latter, having established his credentials in the U.S., returned to China in 2011. As this century develops, under the new regime of free market forces, the Chinese art world becomes ever more integrated with the international art markets, and the majority of the overseas Chinese artists have now returned. Xu Zhongmin and Ye Yongqing have both cemented their places as highly respected contemporary artists, and now judge Beijing as the optimal place to work.

When Philip Dodd introduced us to Wang Huangsheng, early in 2014, we were delighted for a variety of reasons. Here was someone who, as the Director of the prestigious Museum of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, was based at the core of the complex world of contemporary Chinese arts. A specialist, deeply grounded inthe long traditions of Chinese painting, he was intimately familiar with the twists and turns that world has traversed over the last tumultuous decades, having experienced them, as an artist himself, at first-hand. But, most importantly, here was an artist whose own artwork bears the hallmark of that distinctive energy and passion that defines what is of most interest to us: work that refuses categorisation as either ‘Chinese’ or ‘western’, that eludes the restrictive claims of ‘traditional’ or ‘contemporary’, and that mocks the trite euphemism of ‘centres’ and ‘peripheries’. It is as though the ‘mighty river’ of Chinese art having been dammed and diverted and having disappeared from view for half a century, re-emerges broader, deeper and with undiminished power, from a new and unexpected quarter. Surely, it is in this sense, also, that we must understand this exhibition’s title. Despite the long diversionary march of recent times, the line of transmission - reaching back to the primal sources- holds firm and remains unbroken today.

Gerard Houghton

October Gallery, London

Tradition and the Individual Talent

By Philip Dodd

It is one of the most remarked-upon dimensions of twentieth century western art: its need to renew itself by appropriating art from outside its own traditions. What we have come to call postwar U.S. Abstract Expressionism went to Chinese calligraphy to find necessary resources, as has been well-documented by the recent Guggenheimexhibition The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia 1860-1989. Artists such as Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and Mark Tobey became absorbed by East Asian calligraphy, with its sense of order and control; its preoccupation with the brushstroke was borrowed by certain American artists as a way of engaging with the movements of their own body and their own inner workings. Or take Paul Klee and his nostrum that ‘Art does not reproduce the visible; it makes visible’. To make such an art, Klee had to go to the art of children and to that of outsiders to help him forge the necessary language.

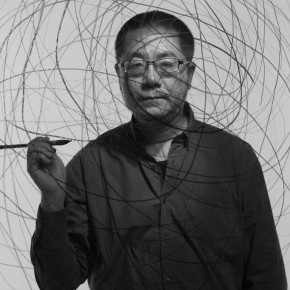

Contrary to their western counterparts, contemporary artists from China do not necessarily find themselves in a crisis of relationship to their tradition, as is clear when I talk to Wang Huangsheng down a line from Beijing. He is someone I have known for seven or eight years, both as an artist and as one of the most influential curators and museums directors, first at Guangdong Art Museum and morerecently at the Museum of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing. His museum experience is relevant to the choices he has made as an artist, in sofar as it has exposed him to installation art and to video - both of which he has practised. But his primary loyalty isto ink on paper, the basis of his show at the October Gallery, and the loyalty is a deliberate choice. And why - because of what the tradition of Chinese ink painting offers him as a contemporary artist. Wang Huangsheng’s art is the art of the line (compare Paul Klee’smuch quoted aphorism that ‘drawing is taking a line for a walk’) and when I ask him what the line means to him, he does not hesitate.

For him the line is ‘a(chǎn) mark of universal recognition’; it also articulates ‘spiritual freedom’, and here he is insistent, it is freighted with the power and resonance that China’s long tradition of calligraphy gives it. ‘Calligraphy is the art of the line, and the lines in calligraphy are the movements of the brush as it moves across the paper’, he tells me. For Wang Huangsheng, the line reveals the real time of the process of making the work (the Chinese way is not to raise the brush or pencil from the paper) but also the ‘time of my heart’ as he calls it. The line is ‘a(chǎn)ble to articulate abstract or psychological concepts which otherwise cannot be expressed’. He repeats a saying in Chinese, 大象無形, which translated means,‘Great form has no shape’ which sounds remarkably close to Klee’s nostrum quoted earlier. Yet if Paul Klee seemed a transgressive artist challenging the post Renaissance separation between writing and visual art to ‘make the visible’, the tradition of Chinese calligraphy effortlessly ensures that there is not nor has there ever been such a separation and remains the traditional and usable form for revealing inner processes (even the tradition of Chinese landscape painting is not primarily a matter of representing a seen landscape but of representing the interior landscape of the artist’s mind).

It is easy to see that western art history, and the museums which are forged by this history, find this troubling. In London, the British Museum collects and exhibits ink painting; the Tate does not do so; in New York, MOMA does not collect ink painting but the Metropolitan does and recently has staged an exhibition of contemporary ink painting which characterized it not only in terms of medium but also in terms of spirit. For western art history, tradition and the contemporary seem almost antithetical. Wang Huangsheng is clear that China’s vision is firmly fixed on the future and on integration with the international world (including theart world) – trends that are both necessary and to be welcomed. Butit is precisely at such a moment, he believes, that it is important, to use his words, ‘to linger on the special characteristics of Chinese culture’. His ambition is to mix the ‘special characteristics of Chinese art with international art to make new cultural forms’.

Like many of the interesting artists of China, Wang Huangsheng came to maturity during the ‘80s, the period of ‘opening up’ after the death of Mao Ze Dong in 1976 – which means also that he lived through the Cultural Revolution, an attempt among other things to cancel tradition. Wang Huangsheng’s father belonged to the Literati tradition of artists and in the early ‘70s was sent into the countryside, as was the case of many others. It was at this time that his father encouraged his son to learn Chinese calligraphy. When he tells me this, I ask him if his father had the opportunity to see his recent work. ‘Yes, he saw it a couple of years ago when he was 103’, he told me. ‘What did he say?’ I ask. ‘Did he like it?’ ‘Yes’, Wang Huangsheng replied. He told me, ‘It is different’. As he said this, it brought to mind Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, the story by the great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, where Menard writes out Don Quixote word for word, only to feel that it is different. Wang Huangsheng’s art is loyal to tradition but in order to make something new, something different; his art shows, among much else, that it is possible to belong to the future without abandoning loyalty to thepast.

About the exhibition

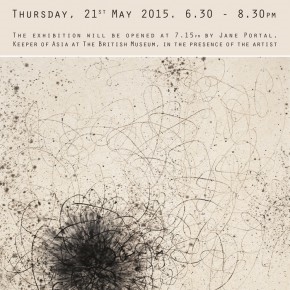

Duration: 14 May – 20 June 2015

Venue: October Gallery

Courtesy of the artist and October Gallery.