At 6:30 pm on January 7, 2019, the lecture “The Birth of Western Art” which was hosted by the School of Humanities at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and co-organized by CAFA Art Museum and Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, was held in the Auditorium of CAFA Art Museum. The speaker was Fred S. Kleiner, a professor of History of Art and Architecture from Boston University and an honorary professor of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. It was hosted by Shao Yiyang, Deputy Dean of the School of Humanities at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and a professor of Art History. In the lecture, Fred S. Kleiner proposed that the birth of Western art traditions, namely “Art for Artist”, a revolutionary idea of artistic creation, happened in ancient Greece in the 500 BCE and he took the rich and informative works of art from around the world as examples to clearly and strongly show the audience the classical revolutionary process in ancient Greece 2,500 years ago. Also, this concept has always been dominating the development of Western art, Dr. Hu Qiao from the University of Glasgow in the United Kingdom served as the translator for the lecture.

At the beginning of the lecture, Professor Shao Yiyang introduced Professor Fred S. Kleiner who is a well-known American art historian who focuses on ancient Roman art and the global history of art. He is also a writer of the popular art history book “Gardner’s Art Through The Ages”, and the Chinese version of the 15th edition of the book has just been published. Fred S. Kleiner was appointed as an honorary professor of the Central Academy of Fine Arts at the International Art Education Conference which was hosted by the Central Academy of Fine Arts in the second half of 2018, so he is going to maintain a close exchange with art scholars in China.

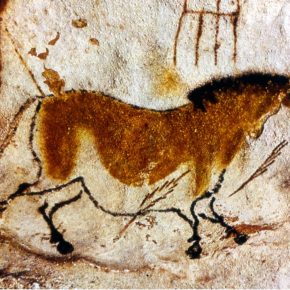

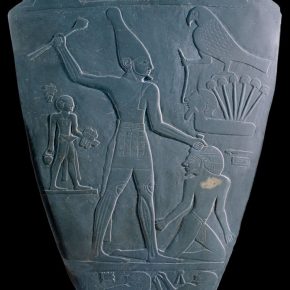

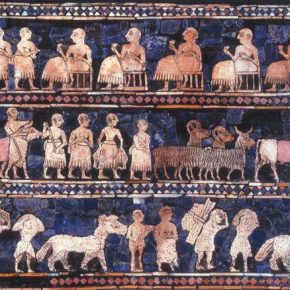

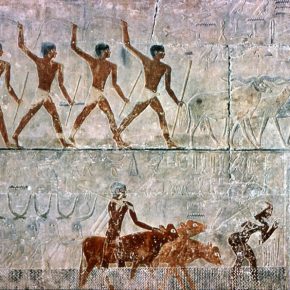

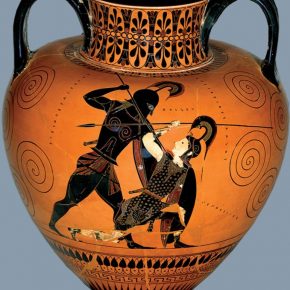

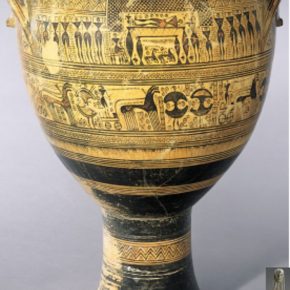

The lecture was composed of the classical revolutions of painting and sculpture. From the prehistoric caves in Spain and France to the big red-figure potteries of Athens, at the beginning of art, the artists from all over the world had the same expression in image-making and storytelling. Seeing the Prehistoric cave paintings, the slate celebrating King Nemer who unified Upper and Lower Egypt, The Standard of Ur by the Sumerians, a colored relief on the wall of a tomb of an official named Ti in Saqqara, northern Egypt, we could find the same artistic features: the use of composite views, the combination of a front view and a side view, to create figures in the form of “hierarchy of scale” to horizontally highlight the most important figures and present stories in strips; in the face of a performing animal, a side view is generally used; and in the case of an animal with two horns, both horns are presented on the screen.

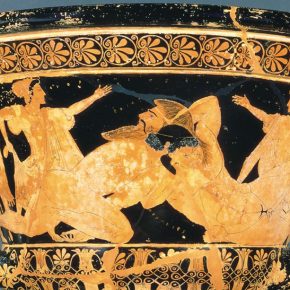

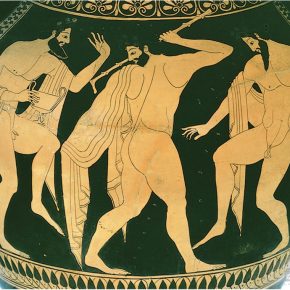

Until 540 BCE, the black-figure painter artist Exekias still applied an ancient composite view to create figures, however, only 40 years later, the red-figure painters Euphronios and Euthymides made an innovation in the expression of figures. Euphronios had broken the rules that the painters had maintained for thousands of years: giving up on the composite view; different from the previous painters, he did not attempt to portray human bodies exactly but to study how to present the human bodies which are really seen, and it became a revolutionary innovation in the history of art. The competitor Euthymides showcased three separated figures on a pottery bottle, and also innovatively represented a man seen as a three-quarter view from the ear. He was so proud of the drawing that he signed it, stating that, “Euthymides paints me, and Euphronios could never do!” The theme of Euthymides is not the “three drunkards dancing” any more, and it focuses on “how Euthymides is better than his competitor Euphronios”, and a theme became a form of artistic creation in the history of art. In Greece around 500 BCE, the idea of “Art for Artist” first appeared. Euphronio’s and Euthymides’s innovations only announced the beginning of the art revolution, and then it was later called the classical style of Greek art.

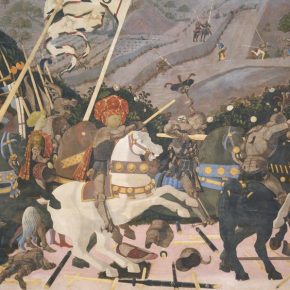

Two centuries later, a replica of a Greek painting, Philoxenos of Eretria, from Pompeii presents a bolder artistic innovation: the artist began to express shadows and reflections, which meant that the artist was both interested in the shape of things, and interested in what those things looked like through people’s eyes, which was a major part of the artistic revolution of the classical period; and the previous system of performing animals being in a side view, was replaced by the performing animals in a three-quarter view from the ear, and this foreshortening deeply influenced art after the Renaissance in Italy, from the 14th century to the 19th century, many works such as Uccello’s “Battle of San Romano” in 1455, Rubens’s “The Lion Hunt” in 1617, and Theodore Gericault’s “An Officer of the Chasseurs Commanding a Charge” in 1812, were the continuation of the painting revolution of the classical era.

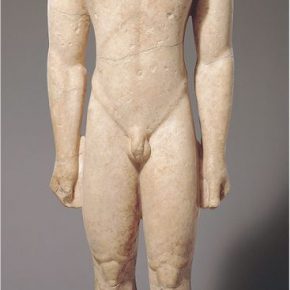

The classical revolution in the history of art was not confined to painting. In sculpture too, the Greeks broke the rules that had existed for thousands of years and made an innovation in the representation of figures, and then a new way dominated sculpture. The ancient Greek art in the early period, the bronze statue is about the same size as the figure painted on the pottery in the geometric period, the body of the sculpture seems to be a triangle, with a tiny waist. In order to show the long hair of God, the sculptor had to spread his neck. Once again, we see an early artist thinking about the human body was an assemblage of independent parts, and each part was presented in the clearest and most descriptive way.

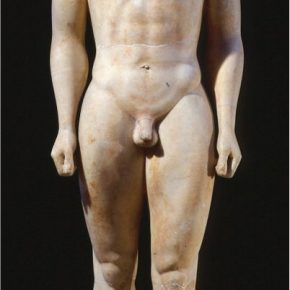

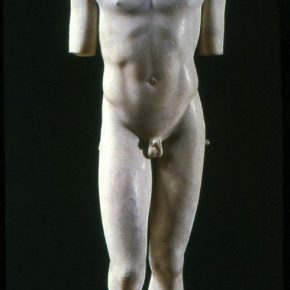

75 years later, around 600 BCE, bronze sculptures that could be held in the palm of one’s hand turned into marble statues that were as large as real people. This was caused by the involvement of other civilizations: Egypt, and also, the Greeks copied the standards and postures of Egyptian statues exactly. However, the statues of Egypt and Greece are different: the Egyptian statue can’t move because it has never been freed from the rock and stone, and it is as eternal as the stone itself; but the Greek artist has already expressed the living human body by removing unnecessary stones. Two generations later, although the Greek sculptor still used the Egyptian samples, the details were carved more naturally, using a more realistic proportion, and at the same time the sense of patterns disappeared. It catches the eye when a face shows a smile because the Greek sculptor tried to tell people that a man is still alive, and only the man alive can smile.

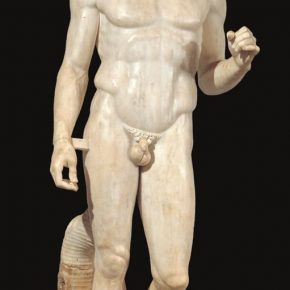

It was not until around 480 BC, the Greek talents finally rejected the standards of the Egyptian statues and turned to use a new posture to represent a standing man. Around 450 BC, in the golden age the Greek sculptor Polykleitos improved on this form, and he created a standing man, naked, in an exaggerated movement, the legs and hips moving forward, arms moving, and the shoulders tilted, the head was turning to the right. He called the writing and statues “The Standard of Perfection”, namely, the ideal statues are constructed by using a harmonious proportion, and each part of the body must maintain a fixed mathematical relationship with other parts, Polykleitos created a strict standard in the posture of the statue, which is called the standard of perfect balance, and he represented art itself in a piece of artwork.

Once again, Professor Fred S. Kleiner stressed that “Art for Artist” was invented in ancient Greece 2,500 years ago and has changed the history of Western art forever. At the end of the lecture, the audience actively asked questions and interacted with the speaker around their observations and the reflections they gained in the lecture.

Text by Zhang Shentong, translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo by Hu Sichen/CAFA ART INFO