"Vernacular: Liu Qinghe Speaks" is the title that Central Academy of Fine Art's professor Liu Qinghe has given to his solo exhibition. Literally speaking, the title means that Liu Qinghe is speaking in vernacular Chinese and not in literary Chinese. However, there is an irony or at least a second meaning to the title that demands further explanation. Liu Qinghe was born in Tianjin. Having a Tianjinese mother myself as well, I am quite aware that the "vernacular" spoken by Liu Qinghe which is not just any old vernacular, but rather the particular vernacular of Tianjin. There is an old saying lampooning the various dialects of Northern China: "Beijing slicks, Tianjin smart-asses, and Baoding slimes". The Tianjinese are known for their garrulousness, and their distinctive patois is notorious for empty boasting. Anyone close to Liu Qinghe knows that the sharpness of his tongue does not pale in comparison to the force of his paintbrush. When asked about his hometown, Liu Qinghe does not fail to live up to his reputation. "Not only are we Tianjinese good at bragging, but we can brag about nothing at all.""Vernacular" thus unites Liu Qinghe's verbal and visual language abilities, attempting to depict the story of his youth. The result is just like the famous roadside crêperies of Tianjin: simplicity and technique culminating in unforgettable richness.

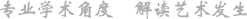

In order to emphasize the functional aspect of this exhibition preface, I'd like to recap my basic understanding of Liu Qinghe's past. Liu Qinghe was born in Tianjin in 1961. At the start of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Qinghe was 5 years old. At the end of the Cultural Revolution, he was 15 years old. At the age of 15, one's gastrointestinal memory, gender identity, life habits, linguistic logic, and even world view are basically formed. Thus, memories of youth are not constructed by the mind, but rather experienced by the body. During the avant-garde "'85 New Wave Movement", Liu Qinghe challenged his fate as a mere artisan (he once studied at the Tianjin Arts and Crafts Vocational College) and was accepted to the Folk Art Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts for his undergraduate degree, studying traditional New Year's pictures (nianhua) and picture storybooks. I can only imagine how the lure of modern art fermenting on the campus poster boards was at stark odds with the traditional content of master Professors Yang Xianrang and He Youzhi's lectures. In 1989, Liu Qinghe's graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts Department of Chinese Painting and the legendary Avant-garde Exhibition of the same year was given a send off with the sound of gunfire. He was given an MFA diploma. Judging from his choice of major, it would seem that Liu Qinghe was never destined to encounter contemporary art. It would have appeared his career and the fashionable games of the 80s were just meant to be passing ships in the night.

In retrospect, such an academic background was central to the growth of the down-to-earth Liu Qinghe. In fact, Liu Qinghe did not take long to make a name for himself. When I was accepted to the Central Academy in 1992, the work of Tian Liming, Liu Qinghe, and Wu Yi was constantly discussed amongst us students. (An aside: in fact, Liu Qinghe and his wife Chen Shuxia were once my teachers. I remember how excited we were anticipating their arrival to the Art History Department classrooms. Compared with writing papers, drawing was much more fun. Years later, when I re-introduced the memory to them, they completely forgot they had me as a student. Perhaps it was because my drawings were really dreadful.In 2007, Liu Qinghe mounted his large exhibition "Beyond the Bank" at the National Art Museum of China. The quality of the works shown, as well as the mastery of the exhibition space made the show truly unforgettable. Soon after, his paintings consistently appeared in important domestic and international exhibitions, cementing Liu Qinghe's position in the Chinese art world.

In 2014, famous Chinese contemporary ink painter Liu Qinghe, already 50 and with a receding hairline to prove it, having been preparing for over a year to mount an exhibition exploring the first half of his life, completed over 100 small yet personal paintings and recorded a 200,000 character long self-interview. The location for such a narrative exhibition moulding text and visuals was set to be the Gallery of the Beijing Fine Art Academy— a location with Chinese traditional, and even conservative implications. The exhibition includes images of Liu Qinghe's changing physical self, as well as images of his father, his brothers, sisters, and relatives, the formerly private 50-room private family residence now occupied by strangers, his former school-year crush the beautiful class prefect, as well as of course his wife, daughter and familiar yet anonymous cities and people... Wielding his brush, Liu Qinghe masters image and language to comment upon his life. Although the figures in his paintings are small, I feel as if their presence is palpable. Liu Qinghe uses their images to analyze the collective memory of a nation, poking at the most anesthetized and numb nerves in your body!

The following text will deal with a few heavy topics, nevertheless requiring a "vernacular" descriptive attitude, including narrative, realism, the masses, humanity, sex, the Cultural Revolution, and the use of mainstream art forms to deal with alternative expression.

1. Narrative Implications

Narrative in painting has been undervalued for quite some time now. "Formal significance" was once the weapon for us to overthrow the pressure of subject-dominated painting. However, as "formal significance" became the object of over-consumption and devolved into "formal insignificance", we begin thus to reflect upon painting that can be communicated verbally. We begin to have a renewed interest in the Dunhuang Buddhist fable paintings, we are once again moved by the image and legend of the "Nine-Color Deer".

Also known as picture books, storybooks are at the lower end of narrative painting, employing image and text to tell a complete story. I once had the honor to curate exhibitions for He Youzhi and Shen Yaoyi. Showing the once wild popular storybooks, "Changes in a Mountain Village" and "Red Streamer on Earth", these texts were not only part of an artistic tradition, but were viewed as cherished memory from the past. I once did an exhibition for young artist Wen Ling; Wen Ling's father Wen Quanyuan was a storybook artist at the People's Art Publishing House. Wen Ling told me that when he grew up, he couldn't help but start drawing six-cell comics, a form he previously looked down upon. Reflecting upon his father's art, he found in turn a great source of enrichment for his current practice. Coincidentally, He Youzhi and Shen Yaoyi were Liu Qinghe's teachers, Liu Qinghe once studied from Wen Quanyuan, and Wen Ling was Liu Qinghe's student. Interestingly enough, Liu Qinghe was also a graduate from the now defunct Central Academy of Fine Arts Folk Arts Department (also known as the Nianhua and Storybook Department). Perhaps within "vernacular" Liu Qinghe became reacquainted with this long-estranged form of expression. The intimate exhibition space at the Beijing Painting Academy will allow the viewers to closely approach these narrative paintings, reading these "children's books" for themselves. In addition, Liu Qinghe will come out with a carefully designed exhibition catalogue, bearing an uncanny resemblance to the Little Red Book. The opening of the exhibition is in a sense also a book release. Liu Qinghe and I will also attempt to organize a Nianhua and Storybook Department reunion, serving as a memorial to a shared memory that should not be forgotten.

2. Realism Nurtured under Limitations

In December of 2012, I once participated in the 5th Shenzhen Art Museum Forum, organized by Lu Hong and Sun Zhenhua. The topic of the forum was "The Socialist Experience and Chinese Contemporary Art". Being born in the 1970s and having experienced that part of Chinese history, I had my doubts about the topic of the forum. However, for Chinese born in the 80s and 90s, the topic was a not an issue. Of course, going through these paintings filled with Culture Revolution mementoes and symbols in Liu Qinghe's studio, I realized that limitations have value in themselves, or in other words that time has a value. Reality as depicted by art is inherently nurtured by limitations. If that art succeeds in having an eternal value, it is because the humanity within the work was effectively expressed, bringing out the eternal quality of its value. The power of the socialist period is thus powerful because of its commitment to true sentiment.

On a side note, I recently had the opportunity to see "Village on the Precious Island" directed by Lai Shengchuan and Wang Weizhong. "Village on the Precious Island" is the story of a vicissitude of a small military village during the Kuomintang occupation of Taiwan. It was a simple, narrative play. One viewer wrote on Weibo after viewing the play: "It moved me to my core". The same review was given to "Nirvana of Granddaddy Dog", produced by the Beijing People's Theater. As plays recounting memories of decades gone-by, their eternal artistry owes to their commitment to humanity and true sentiment. They are not "false poetics", but rather folk songs from the heart. I encountered the same pursuit in Liu Qinghe's hundred paintings and accompanying texts. They do not depart from the banal realism to which we are accustomed, but rather from a place of true personal expression.

3. The Strength of Silver-tongued "Vernacular"

I am constantly astonished by the power of Liu Qinghe's language, whether his verbal vernacular, or his prose. Reading his writing, I am often reminded of Lao She'sMr. Ma and Son: Two Chinese in London and The Life of Niu Tianci or and Wang Shuo's Animal Fierce or Half Flame, Half Sea Water. Liu Qinghe's 20,000 character self-interview is both classic and unorthodox, a true revelation of the soul. I now understand why people say that artists hate themselves the most; they are willing to uncover their scars to others.

Take for example Liu Qinghe's childhood love. "The sort of love you remember, the kind that comes from the pit of your stomach is always unrequited. Unrequited love never works out; that's why it's called unrequited love. I experienced unrequited love throughout my childhood, from falling in love with my female teacher, to falling in love with my classmate. When I fell in love with my classmate, I finally felt as if I had grown up, that I was now mature. I have always liked girls they were indifferent towards me, girls that were haughty and proud in front of me, girls that would bat out orders, girls that were stern and serious. I've always had a weakness for girls that inspired fear in me."

Strength of language comes from deepness of thought. Liu Qinghe's most acute description is that of his father. Liu Qinghe recalled: "I slowly came to understand that although having no thought and not thinking are two different qualities, once my father possessed them both, he accidentally found the perfect way to deal with the past century of Chinese history. In his eyes, the need to go on living was not only taken for granted but was an undisputed reality. The past was a given, not to be questioned. It was this natural survival and recovery method that made him a lucky man." Liu Qinghe's father's "weakness" became a sort of wisdom, enabling his family to make it peacefully through the storm that had enveloped Chinese society, while perseverance and sensitivity would perish during the journey. This is why Laozi's dictum, "The softest thing in the world dashes against and overcomes the hardest," has been quoted over and over again— not only because it applies to many situations, but also because teeth never last as long as the tongue. I remember that someone once told me there are three ways to deal with problems: 1. Resolve them; 2. Put them off to the side; 3. Don't view them as problems. In believing that life has no right or wrong, Liu Qinghe's father made the most natural choice.

4. Painting and Memories of the Past

I must discuss Liu Qinghe's paintings and their relation to memories of the past. Liu Qinghe's paintings are city-people’s paintings; they have the line and color of city-people. When compared with the pastoral leanings of traditional Chinese painting, Liu Qinghe's work draws a strong contrast— in both his strength, and the reason why he is sometimes criticized. I'd like to mention Tianjin yet again, that once proud and developed port city. In my memory, Tianjin of the 70s, with its neon lights, Kissling ice cream, and tall Western architecture, was much more fashionable than Beijing. Thus, we can often feel a certain "Western style" in Liu Qinghe's work; perhaps petit bourgeois, but not bobo. Like the floral embellishments of a Corinthian column, his style is dazzling and not frivolous.

The marks of an age have not only left their trace on his skin, but have carved their way into his bones. Red neon lights, the Little Red Book, little red scarves, the Red Detachment of Women—fiery and sexy, I can imagine how effortlessly these images emerge when Liu Qinghe picks up his brush, with no need for forethought. His eye-less figures with their empty pupils are a response to the act of recollection and reconsideration of an age. The fragmentation of history is in effect its value; oft-ignored group consciousness has been intermingled with the themes of city life, globalization, ink painting, and contemporary art. All these elements are gathered within the melting pot of reflection, put out to dry, and then examined to see what it all tastes like. Youth are hot-tempered and passionate; we call them provocative. Adults are restrained; we call them cunning. One who is successful without being cunning is an eternal child. Liu Qinghe has strived to preserve, search for, and capture the "eternal child" within his art──although this eternal child cannot help but bear the mark of time.

In conclusion, we are excited to present an exhibition with "vernacular" from the heart, as well as a "vernacular" text, hoping that it will leave you with a faint yet powerful memory.

Wu Hongliang,

September 24, 2014, Wangjing, Beijing