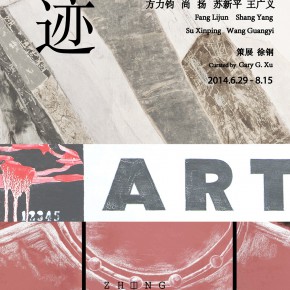

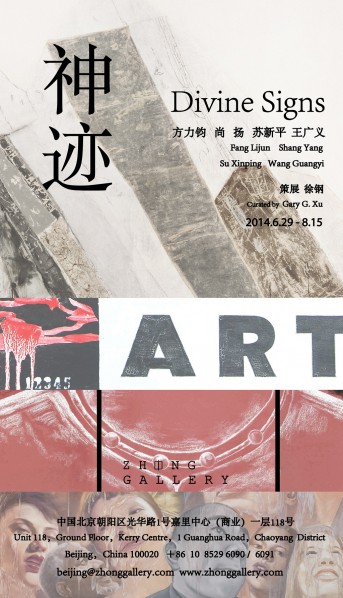

From June 29 to August 15 2014, Zhong Gallery will hold a group exhibition Divine Signs of China contemporary artists, which is schemed by the well known curator Xu Gang. The artists are: Fang Lijun, Shang Yang, Su Xinping, Wang Guangyi. The exhibition will be displaying the creations of the four artists in recent years.

Divine Signs: Fang Lijun, Shang Yang, Su Xinping, Wang GuangyiBy Gary G. Xu

One of the characteristics of modern art is transcendentalism. Modern artists are disillusioned by the enormous but unrealistic promises of modernity in the aspects of ever-increasing efficiency and universal materialism. They can also be angered by the fragmentation and alienation of humanity due to the hegemonic developmentalism. In either case, the artists resolve to call upon the divine to express their disillusionment, anger, or defiance. This has given modern art its multiplicity of meanings: whatever the theme, a masterpiece of modern art is never limited by its immediate visual expressions; there is always another layer of meanings higher than and transcendental over the familiar objects.

The four masters of contemporary Chinese art showcased in this group exhibition all share the traits of transcendentalism. Wang Guangyi (born 1957), for instance, has been consistently relying on the divine to intervene in the politics of the contemporary world. In Demetrio Paparoni’s words, Wang Guangyi “deifies the human and humanizes the divine”: “The key motivation behind the art of Wang Guangyi lies in the idea that history is guided by a project that for men of faith leads to transcendence, for Marxists to proletariat triumph, and for laissez-faire capitalists to economic laws that should guarantee the self-regulation of the market.”1 In other words, Wang Guangyi’s art manifests the trajectories of transcending the status quo under the demand of different ideologies.

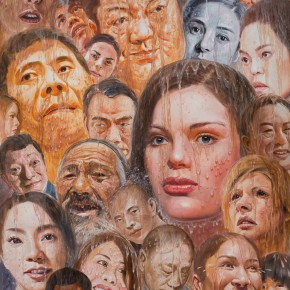

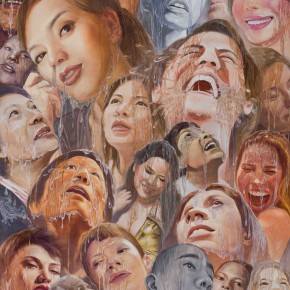

Fang Lijun (born 1963) might not agree to be linked to the divine. After all, he is the kind of artist who draws inspiration from everyday life and from individual experiences. To him, there seems to be nothing sacred or transcendental about art: “Life is the main thing; art is only secondary.”2 But his refusal to be interpreted in technical details or to be treated as an artist who dwells in the fragmented everyday betrays his real intension, which is to jump out of the everyday experience so that he can reflect upon social realities and historical atrocities.

For Shang Yang (born 1942), who is masterful in yoking Chinese traditional styles with modern motifs, the divine is equal to the highest realm of artistic pursuit, a realm so pure and inaccessible that the journey towards it matters the most. His abstraction, which is termed “the third abstraction” by Zhu Qingsheng and Gong Xiaoman, is imbued with the desire to transcend the mundane world through the expressiveness of bimo (brush and ink).3

Su Xinping’s (born 1960) experience growing up in Inner Mongolia has made him more sensitive to the divine or the transcendental than others. The vast grassland and the boundless horizon led Su’s thoughts go far and beyond the everyday. Mysticism cast a long shadow over every piece he has ever made. This long shadow has both psychological and compositional significances. Psychologically, the shadow gives his work a strong sense of doom and melancholy; in terms of composition, the shadow takes the form of clean lines and geometrical shapes in Su’s printmaking and oil paintings.

There is no denial, of course, that modern art is a continuation of the defiance against the dominance of religion in the medieval period. The manifestation of the divine in modern art differs greatly from the religious themes: the divine, for modern art, is not the end, but a means by which issues in the everyday are complicated, questioned, and estheticized. This is especially apparent in the four artists in this exhibition.

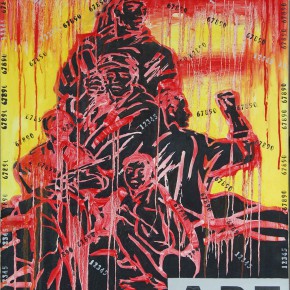

Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism (2008) series are even more important than the original Great Criticism paintings that earned him worldwide fames. The appeal of the original Great Criticism paintings lies in the stunning juxtaposition of capitalist consumerist icons with the divine images of the Communist revolution. The new Great Criticism paintings leave behind those familiar icons and point instead to more abstract words: NATION, FAITH, and ART. These are loaded words, all possessing powers of totality and each indicating a whole set of ideologies. If these words must be understood in their totalities, the revolutionary images by contrast become far more unstable and fragmented. The original Great Criticism images did not separate themselves from the ubiquitous Cultural Revolution Period posters; these new images, however, are peeling away and melting as the paints drip freely. The divine could be these images or those loaded words. The artist does not attempt to arrive at the divine powers; instead, he returns the divine to the mundane and questions the power of totality.

Su Xinping’s two Portraits, one of 2010, the other of 2012, look identical to each other except the hand gestures. Su Xinping has given adequate explanation to his intension in these paintings:

I began to paint this series of Portraits since 2004. Each piece consists of nine blocks that can be arranged in random orders or in the order of a normal portrait. If arranged randomly, the works present a visual experience of chaos and thus point to the fragmentation of reality… If the head that gazes upward is about metaphysical thoughts, then the changes of the hand gestures point to circumstances in reality and desires. To me, whether the representation is fragmented or not, the issues at stake are similar: they all disclose people’s actual existence and spiritual existence, and they all explore the relationship between reality and idealism.4

These astute observations help us understand how the divine is only Su Xinping’s tool for reflecting on reality.

The Dong Qichang Plan is Shang Yang’s most important work. As many have pointed out, Dong Qichang is only a randomly chosen name; that Dong happened to be a true innovator in the history of the Chinese painting only makes this name a better disguised divine means by which Shang Yang expresses his desire to return to the materiality of bimo. There are many branches and styles in traditional Chinese art; the literati painting is the only style that consistently draws attention to the materiality of the medium itself instead of seeking some otherworldly spiritual realms. The more we are focused on the medium, not the clichéd themes, the more we can assert our uniqueness and personality. The literati painting is one of the most important means by which the Chinese men of letters preserve their independence and moral integrity throughout the long Chinese history of violence and disturbance. Shang Yang, in his minimalist appeal, seeks to continue this literati tradition and to cast questions on the form itself.Fang Lijun’s upward looking figures are showered in gel-like liquid. The irony is unmistakable: in asking for rain, which is symbolic of the material wealth that everyone in contemporary China is after, the figures receive a glutinous gel of dubious nature.

One of the time-honored narrative devices, which was perfected by Alfred Hitchcock in his films, is the McGuffin. This is an object of desire or a goal that the protagonist pursues with little narrative significance. Once the plot moves on, the McGuffin is quickly jettisoned. Isn’t the divine in the four masters’ paintings similar to the McGuffin? It loses its significance once our attention is drawn to what actually matters to us. The ability to use the divine as a visual tool and an ideological camouflage, however, separates these artists from others.

1 Demetrio Paparoni, Wang Guangyi Works and Thoughts, 1985-2012. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2013, p. 11.

2 Fang Lijun, “Live like a Homeless Dog,” in Lv Peng and Liu Chun, eds., Fang Lijun: Collection of Studies. Beijing: Culture and Art Publishing House, 2011, p. 978.

3 Zhu Qingsheng and Gong Xiaoman, “Shang Yang fengge yanjiu chugao, jian lun disan chouxiang” (An initial study of Shang Yang’s styles in terms of the third abstraction), in Shang Yang. Hefei: Anhui Art Publishing House, 2012, pp. 58-87.

4 Su Xinping, “Remarks on the Portraits,” in Yang Wei, ed., Su Xinping, Changsha: Hunan Art Publishing House, 2013, p. 193.