Veneer of the World

By Zhu Zhu

Amiasma of instrumental thinking about art has long pervaded the airspace over China, and works of imaginative beauty are often treated as if tainted by original sin. This state of things is even now being carried on in bizarre fashion: if an artwork does not testify about adversity or oppose an ideology, the artist may seem to suffer from moral dwarfism. What is more, a Cavafyesque sigh can even be heard from the Western world: “What sluggish Asian—blind and mute—resigned to blind mute destiny?”1

For any given person, biopolitics will shape a particular yet extremely hard-to-trace orientation. Expressive acts may constitute a form of opposition that is all the deeper and self-aware precisely because they deal with imaginary beauty. Ideology is everywhere—this is something we have learned from Foucault’s philosophizing, and Lyotard has reminded us: “Perhaps the political unconscious is to be found in all artistic texts.”2 If we peruse Xu Lei from this angle, we will discover that his fine brush fabrications, be they ever so immersed in imaginary beauty and seemingly insulated from politics, are actually a reverse formation drawing upon ideology. The space which he encloses with drapes or screens is not an aesthetic utopia or a priori world thrown open to our view. Rather, it is a passageway between external and internal worlds, or one could say it is a shell which reveals a glimpse the inner world.

In that zone the color blue has chased away the color red; soliloquies have banished outcries; elusive experience has replaced ardent effusions on revolution. Ancient palace-style paintings have been stripped of their mannered approach to lavish erotic themes—this is Xu Lei’s way of counteracting the crude, garrulous political exhibitionism of our era. Xu Lei’s strong suit lies in casting aside ideological imagery and rhetoric, making good on his vow that “my ink art will not follow along with the times.”3 In fact, Xu Lei has not moved all that far, and perhaps he only took a single step, but this step went in a direction counter to ideology. Now that he has won broad approval, perhaps he owes a thanks to ideology first of all—without its pressure, his gracefulness could not have shown itself; without its “substance” he could not have shown his “empty openness.”

Moving towards Interiority

Back in the 1980s, when China’s modernist enlightenment was fomenting the ’85 New Art Wave, Xu Lei took a quizzical stance toward Li Xianting’s statement—“Art is not the important thing.” With respect to art, if the important thing is not art, then what is it? One thing that prompted him to set off in search of imaginary beauty was an anecdote from a faraway country. There was a time when surrealists in France marched on the streets and tried to outdo each other at shouting political slogans. Only Jean Miro timidly chimed in: “Down with the Mediterranean,” which only earned him ridicule. A few decades later, their much-admired figurehead Stalin was proven to be a practitioner of terror. Only in one respect did their political engagement deserve to wear the medal of “greatness,” namely for bringing down the Mediterranean. Indeed that womb of European classicism was severely shaken by surrealism.

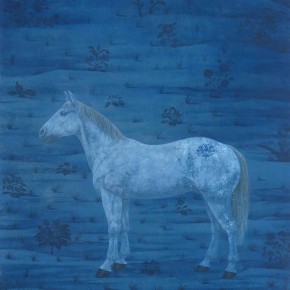

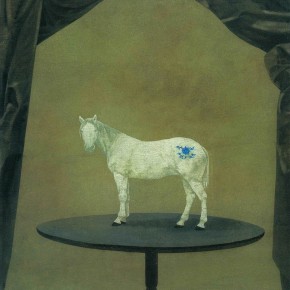

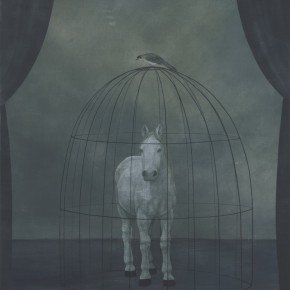

In the terms of Renato Poggioli,4 Jean Miro belonged to the “artistic-cultural avant-garde” rather than the “political avant-garde.” The mission of the former was more an aesthetic revolution, directed at art history; it was a moment of inward subversion or perhaps adventure. This was doubtless more in tune with Xu Lei’s dreams and compulsions. Even in his initial period of experimentation with various materials under the lure of conceptual art, his rubrics of concern did not relate to social salvation; instead, they were “the closer you get to beauty, the closer you are to death” (Heart and Lungs Normal, 1986) and “traces of non-existent history, captured on ink rubbings from road pavement” (Crevices, 1987). Both of these pieces were shown in the 1989 China Contemporary Art Expo, but they clearly went against the prevailing mood of ideological opposition. In these pieces we see indications of his individual taste: everyday associations, fascination with details and melancholy daydreams. At the same time, in terms of rhetoric they affirmed his own traits: chicanery with images, surreal assemblages, and passion for form. One can discover that he did not invent anything; rather, he engaged in pastiche, assemblage and grafting. (His paintings of a horse bearing blue porcelain patterns mark the high point of such rhetorical devices.) After these pieces, under influence from T. S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” he consciously turned his face toward tradition. He persisted in using ink art materials to express himself, thus distancing himself even further from the avant-garde types.5

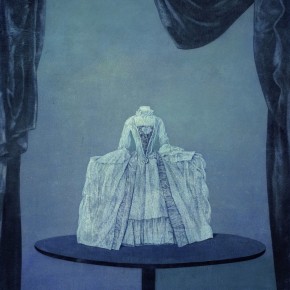

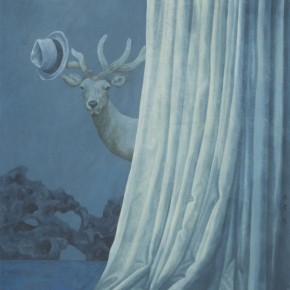

“My ink art will not follow along with the times.” For Xu Lei, uttering this statement was tantamount to choosing self-banishment, in order to pursue “the purity and beauty of defeat.” In his view, to be misled for a long period by a superficial posture of opposition would be no different from “internalization of confinement.” What is more, he would unthinkingly be playing hostage to ideology. Such art might seem to be filled with righteous force and courage, but in terms of aesthetic creativity it would have little to offer. Meanwhile in his own liminal meanderings, he instinctively dredged up segments of Qing-era history that gave off a decadent mustiness. Some of his works during that period were reconfigurations of old palace photographs. His pictures had a look of static blankness. Drapes were drawn halfway between reality and dreams or observation and hallucination, thus being put to use as props for his rhetoric of suggestion.

In fact, among the types of Western modernism, Xu Lei’s personality fits into “anti-modern modernism.” In the book Five Faces of Modernism, Martin Calinescu discussed anti-modern modernism in his section on “Decadence.”6 This pertains to a decadent aesthetic sense inherited from French symbolist poetry: it expresses a sense of decline as history develops towards a terminus. It finds present reality to be hollow a meaningless. In words from a poem by Baudelaire—“Souvenirs? More than if I had lived a thousand years!” Just as Symbolist poets were fond of borrowing themes from the Roman empire’s decline, Xu Lei’s historical montages also favored the aspect of overindulgence and sensuality. Unlike “cynical realism” and “new literati paintings,” which responded to social conditions with hedonistic carnality, his treatment corresponded to our modern sense of jarring change and temporal flux. The Yangtze River region where had lived much of his life was the most refined and decadent locale of traditional civilization. Thus his temperament seemed to take on a fading glow from the favored sons, literati and wastrels of those bygone days.

What helped him dispel the demoralization of being a holdover, letting him establish his own inward sense of order, was the aesthetic of labyrinths. In literature there was Borges; in psychology there was Freud; in film there was Antonioni7…all these served as keys to probe secrets of the labyrinthine aesthetic. Thereupon a thread of possibility began to appear. It was not just a matter of reworking an aesthetic form, for it also touched on a way of looking at the world, acknowledging an inner world we cannot see. Or one could say that behind surface phenomena there is an interior which is filled with marvels and unknown depths. That place is the garden of the unconscious; it is also the psychological site where history and memory intersect with personal fantasy. To move toward it is to move toward a space where illusion and genuineness are both intensified.

The Shell over the Interior

In terms of rhetoric, Xu Lei’s labyrinthine configurations are first of all a transformation of surrealism. To sum up the features of his painting in a few words, they are “substantive forms laid out emptily.” “Substantive forms” means that he paints various images in a concrete, realist way; “l(fā)aid out emptily” means that relations among these images are merely virtual: they give a Lautréamontian8 sense of coming together randomly. As Xu Lei puts it, “What really appeals to me is not how to paint but how to play with the cerebral, rhetorical relations among images.” Even so, if the usual Western surrealist practice is a kind of “welding” or violent yanking together of images, then Xu Lei is fonder of interweaving them tenderly. Even assemblages that could seem jarring, once they are rendered on his painted surface, tend to accommodate themselves to each other, joined by softness like silk threads or lapping ripples.

Aside from surrealism, he also soaked up expressivity and image-ideas from Klein,9 Duchamp, and even from Vermeer, Velasquez and Van Dyck. What is more, aside from drawing on the canon of Song-era academicism, he also gleaned insights for pictorial structure from ancient garden design, with its successively changing vistas, and from woodcut illustrations in Ming-era printed dramas. From all these he put together his own look which was quite different from “minor inventions” in ink-and-wash which traditionally minded painters content themselves with.

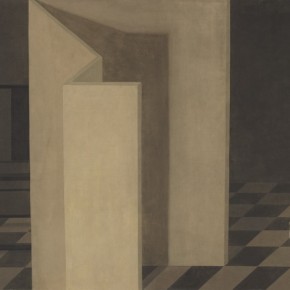

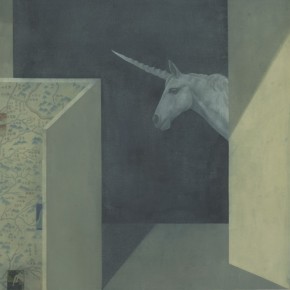

In his typical layout, the outside world is set apart by drapes, and a screen leads the line of sight into a secluded inner space which holds an ambience of mystery. However, we ultimately discover that only indefinite forms exist in that space—exquisite, erotically-charged oddments. In other words, what we see of this internal space is also an empty shell. We can only get a glimpse of this internal space, but we cannot situate ourselves there.

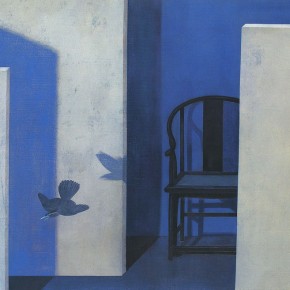

In fact, the more one understands what painting is, the more one understands its limitations. Painting can only carry so much freight. It is not a weapon for directly amending the world, and it can never be an absolute representation of the inner world. Yet through spatial imagery it can elicit our surmises as to the essence of things in the world. In this sense painting remains a surface—a surface relating to essence or depth. As Hofmannsthal admirably put it, “Depth is hidden, and where? At the surface!”10 In Xu Lei’s paintings, the surface adumbrates depth through mirror images that flash obscurely into view, prompting a desire to go after them. Eroticism is treated as a means of enticement for a textual effect which Roland Barthes described as joy and pleasure. Is there anyone who glimpses a skirt-edge rounding a corner who does not wish to trail after it? But when you go around the corner, what you find will not be a smorgasbord of carnal gratification: by glimmering light you will see a few Ming-style chairs, perhaps with the silhouette of a flying bird cast upon a wall. The woman, who is perhaps an alter ego of Ariadne,11 has vanished without a trace.

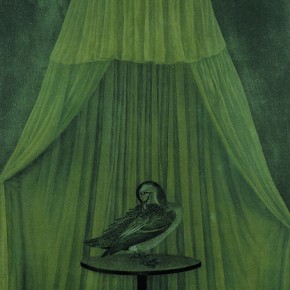

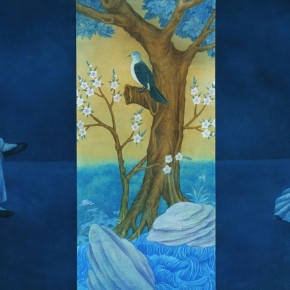

Along with the defeat of erotic expectations, the sense of empty illusiveness is reinforced. However, what presents itself before us is not total vacuity, for a textual memory of art history begins to manifest, and it becomes subject matter upon which we can linger. As for things he is fascinated with, he puts them forth in an offertory spirit, presenting and highlighting them in a ritualized manner. A feathered creature such as Emperor Hui would have painted is displaced onto a round table, seen through half-drawn drapes. This is not only a nostalgic reference to a classic with its irretrievable provenance; it is at the same time an emotive metaphor for the constitution of self through appropriation and revision.

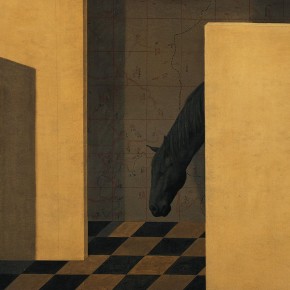

If we say that for Vermeer a map represented the inferred presence of the outside world, then for Xu Lei a map is visual evidence that actual history—the external world of the past—has by now dissolved into mist. “To thrive or decline is the way of men’s fortunes/ Mountains and rivers merely set the scene.” For Chinese people human life is impermanent, and even prosperity will rapidly be emptied of substance. This is the realization and emotional tenor behind the Oriental aesthetic. As Stephen Owen emphasized, remembrance was not just the literati’s convention of nostalgia for a fallen capital; rather it was a lyrical paradigm that informed the whole tradition.12 In Xu Lei’s work, a map is the outermost shell of geographical terrain, and it bears two layers of remembrance—the “vanished presence”13 of historical entities and the “vanished presence” that belongs to traditional aesthetics as a whole. In “Record of an Empty City” (2000), the picture shows a black horse’s head protruding from behind a screen. The horse seems dazed, as if it has lost its way, and the place where it has arrived looks like a hidden chamber, dim and enveloped in shadows. In the dimness one can perceive endless winding spaces. On the screen which delineates this part of the labyrinth, one sees that a map has been painted, but the place names have all been concocted by the painter in place of rivers, mountains, towns and villages that had once been there. This whimsical substitution removes the map from the sphere of geography, placing it in a fanciful realm of dreamed-up appellations: this gives play to an individual’s fancy private desires. This painting belongs in a series with “Record of Return to a City,” “Record of a Lost City” and “Record of a Remembered City.” Each of these pieces moves back and forth along the borderline of historical textuality and personal experience.

Perhaps by entering deeply into such a picture, we can come close to finding the thread and solving the labyrinth: it is a site where visual forms of eroticism and history interweave, yet the artist is plainly proclaiming their illusiveness as well. With a magical combination of images he is evoking sensual “form,” but at the same time acknowledging its emptiness. Emptiness is at the center and all object-forms point to that center, but at the same time they cover up that center. Thus we see a spatial realm which is partially curtained off, poised between openness and hiddenness. With its erotic forms in miniature style it lures viewers to enter. Rather than to say they enter, one should say that they stray into this space. This is why the space in his pictures does not recede perspectivally, thus hinting at its continual extension before it is given over to the ultimate void. Thus one should say that this interior, this inner world that he acknowledges, is emptiness in its original sense from Oriental cosmology.

A New Dialectic of Space

Emptiness-as-being, rather than emptiness-as-non-being, stands at the limit that is accessible to art. Art’s hallucinatory presentation of object-forms cannot be reduced to a thorough void. As Tanizaki Junichirou14 wrote in book In Praise of Shadows, “Beauty does not exist in physical objects; rather, it exists in the shadows produced between objects, with their ripple-like nuances and shading…Dispensing with the effect of shadows, there would be no beauty.” The labyrinth constructed by Xu Lei can also be construed as a place of shadows. The surreal placement of objects also sets up ripple effects which lap against its surfaces. Pieces like “Azure Mist” (1996) and “World Pond” (2007) emphasize an individual stance through the act of reading—carefree and languorous beyond all help. It refuses the call of reality. It is immersed in textual imaginings and memories of history. Yet behind that drape or screen there is perhaps an implicit resistance to ideology. If it is there, it lies within layered folds which shut out the outside world. These are the fortifications which he has designed and erected.

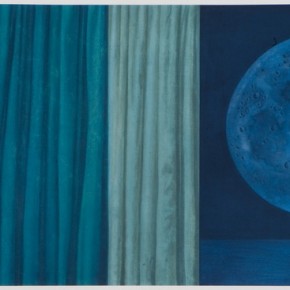

If one merely paces about through such a self-designed labyrinth, watching the vista change with each step, this will merely enact a visual fantasy novel in episodic form: at some point one’s personal stance will solidify and lose spiritual direction, becoming a mannerist shell. Parallel to this a different issue arises: once one leaves the shadows and emerges from the labyrinth, does this mean that beauty, depth and mystery will have no grounds to exist? In 2006 he moved from the Yangtze region up to Beijing. The positive significance of this move was that it let him jettison the highly wrought, convoluted side of his temperament so he could move toward pared-down, condensed thematic treatments. In “Moon Curtain” (2009) he dispenses with the past air of finesse in his paintings, highlighting a sense of space-time as an oceanic expanse. On a painted surface tinged with dusky blue, two images are combined—the moon and a parted curtain. The moon is rendered in a nearly photo-realist mode, and the parted curtain appears at both sides in the foreground. Viewers seem to be gazing out from a room interior at the moon above. The once-closed space of his paintings is here thrown open: we see that inner versus outer and nowness versus eternity are being imagined dialectically.

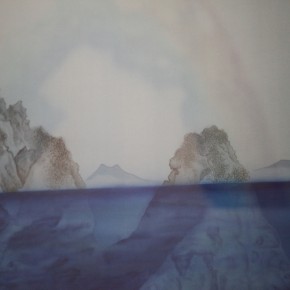

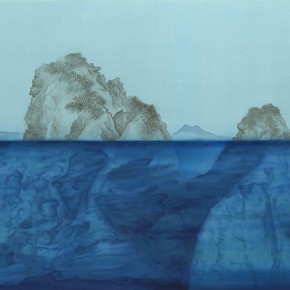

In terms of metaphysical geometry, space of the inner world has never been opposed to the external world. As Gaston Bachelard remarked, “Wasn’t external space once an inward space which vanished into the shadows of memory?”15 Such a dialectic undoubtedly calls up the echo of Zhuangzi’s “Free and Easy Wandering.” For Xu Lei, this constitutes a new starting point for discourse. In the painted silk “Rainbow Rock” (2012-2013), the rockery stretching across the painting seems to have been assimilated to the arc and shape of a rainbow. Perhaps one can say that the two images, one man-made and one natural, have been superimposed as one. The rock’s substantive image has been emptied by the rainbow’s illusory image. An iridescent succession of colors highlights the mutual grounding of form and emptiness of which Buddhist scriptures speak. In the series “Breath and Bone” (2012- ), the ocean’s surface divides a massive rock, counterposing realistic drawing to freehand style, reconfigured images to representation of nature, and easefulness to endurance. In his large-scale “Drifting Floss” (2013) a rope crosses the painted surface, presenting a conception of lightness versus weight and existence versus nothingness. All these pieces indicate that he is striking out in new directions from his former self. The labyrinth is being thrown open, and that familiar thread of individualism now appears naked and trembling, waiting for a tie to the next segment, so it can be balanced and extended indefinitely.

September 2013

Tr. by Denis Mair

1 ... Quoted from C. P. Cavafy (1863-1933), “The Word and Silence.”

2 ... See Jean-Francois Lyotard (1924-1998), The Political Unconscious.

3 ... This is a reversal of Shi Tao’s statement—“ink art should keep up with the times.”

See Kugua heshang huayu-lu (Recorded Painting Talks of the Bitter Melon Monk).

4 ... American art theorist who wrote Theory of the Avant-Garde.

5 ... See Zhu Zhu, “Xu Lei: Another Countenance.”

6 ... Shangwu yinshuguan (Commercial Press) 2002 edition.

7 ... Michelangelo Antonioni (1912-2007), Italian film director whose works included Blow Up.

8 ... Comte de Latréamont (1846-1870) was a French forerunner of the Surrealists.

9 ... Yves Klein (1928-1962) French artist; the color International Klein Blue (IKB) was named after him.

10 ... Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929), Austrian writer and poet.

11 ... Ariadne was a female character in Greek myth who helped her lover find his way out of King Minos’ labyrinth.

12 ... Stephen Owen is an American scholar who wrote Remembrance: The Experience of the Past in Classical Chinese Literature.

13 ... “Vanished presence” refers to a-a-eté,

an idea about the essence of photography which Roland Barthes expounded in his book Camera Lucida.

14 ... Tanizaki Junichirou (1886-1925), Japanese writer.

15 ... Quoted from the translated version of Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962), The Poetics of Space, Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Courtesy of the artist, for further information please visit xulei.org.