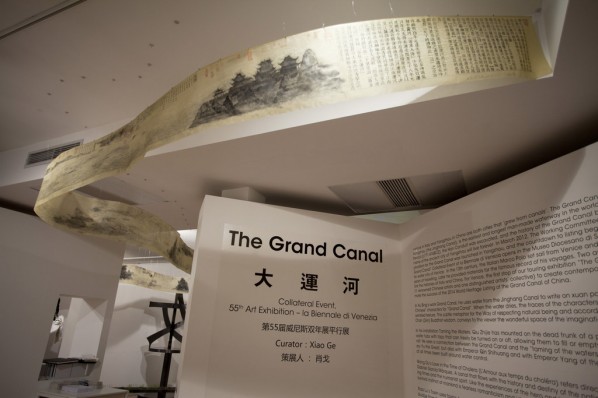

The Grand Canal team arrived in Venice on 19th May. With 10 days of installing and preparation, the exhibition finally opened at 6 pm on 30th May at Museo Diocesano Di Venezia, which is located beside St Mark’s Square. As the curator Xiao Ge said at the opening ceremony, “Though the size of the exhibition is quite small and the time for preparation was very limited, we have been through all kinds of hardships and difficulties that were like the winding exhibition room upstairs, and which are inevitable for success…Fortunately, this collateral event of the 55th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia ‘The Grand Canal’ has successfully opened.”

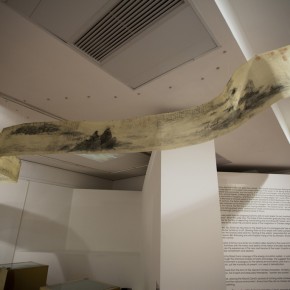

It has taken our installation team, which was led by Guo Lijun, Li Liangyong and Jia Hongyu from The Irrelevant Committee, great efforts to achieve the perfect exhibition effect, under the premise of retaining the ancient architecture that was built in 12th century, in the Museo Diocesano Di Venezia intact. Upon entering the exhibition, you will first encounter “The Flow of Energy” by Zhang Yanzi, a 64-meter silk scroll with ink and wash painting, winding while suspended from the ceiling. The scroll, which portrays rivers, main and collateral channels of the earth, and the ceaselessly surviving canals, snakes through the exhibition room in the form of a river, and establishes ties among all the works in the exhibition. The artist presents this traditional ink and wash painting in the form of a contemporary installation, and has made several adjustments to the way of installing as well as the length, position and direction of the fishing line, in order to get the most satisfactory result that resembles water flowing in the sky. The Flow of Energy, a kind of mysterious power, a kind of healing capability, a kind of stream of consciousness. Rivers, main and collateral channels of the earth, flow and bring about vital water and energy evaporating in the air.

Right under the “Canal Scroll” by Zhang Yanzi and near the entrance is located a set of sculptures by Peng Xiaojia, from his “Landscape” series. This sculpture group is composed of three maple sculptures with different colors. It is presented in the form of a volcano, enclosing flowing golden streams, which is full of elegant amusement. The artist is trying to convey the idea that water originates from a high place, flows from high to low, and runs a long course from a remote source. The water of the Grand Canal comes from living rivers, between the excavation and nature, as intimate as mountains and water.

At the other side of the “Canal Scroll”, two installation pieces by He Haoyuan (He Yuejun), which are the Buddhist and Taoist part of his “In the Beginning” series, run with a great roar. This work uses religious prayers as the sound source, and turns the particles on the sounding board to images of religious zeal including an eight-petal lotus from Buddhism and the round-sky-and-square-earth pattern from Taoism, by using wave-particle dualism. The origin and development of human civilization is inseparable from rivers; the Grand Canal is a masterpiece that resulted from human conscious intervention in nature for cultural communication; and Buddhism and Taoism have spread through the Grand Canal in China. This series is trying to describe the strength of belief with waves from the essence of the physical world.

At the center of the exhibition room is the installation “Canal Transportation” by Qiu Zhijie, which also corresponds to Zhang Yanzi’s “water up in the sky”. The artist has collected seven used wooden benches from ordinary families along the Grand Canal and joined them together to form a man-made channel on the ground. Grooves have been cut at the center of the benches then filled with soil and sown with wheat seeds. Due to the time limit, the artist and his assistants had to explore several methods to speed up the sprouting. A fair amount of green buds, fortunately, have grown in the “channel” on the day of the opening ceremony, which was quite beautiful. As food is the most basic need of man, Qiu Zhijie considers the significance of canals as more of a connection to the national economy than merely cultural transmission. On the previous day of the opening ceremony, Qiu broke all the chopsticks placed along the wheat buds, and mocked it as it implies a “peasant’s revolution”.

In comparing the Great Wall to a masculine man, then the Grand Canal is more like a feminine woman. The installation set “Women” by Huang Rui has combined the Grand Canal’s boldness with its vividness. During the installation, it took tremendous effort to assemble these two installations. This bold black “woman” could finally move and spin like flowing water, and dance without betraying any emotions… Just as the artist has put it, “Women are women; the Grand Canal is like women.”

“Be out of Control” series by Gao Jie, discusses the uncontrollable situation resulting from fortuitous fringe imaginings. The artist has brought several mysterious monsters to the exhibition. The style of these river deities, some in the shape of a computer or a cellphone, come from the traditional supernatural masks. The masks were made with ordinary stuff and fixed onto a table with their teeth made of metal flatware biting the table edge. Gathering around the high table, they stare into the eyes of the audience who are sitting below. River deities are the combination of “l(fā)ife and inheritance”, as well as the consciousness that is contradicted and opposed to the “individual”.

Around the corner of the exhibition room is located “1794 km Resources’ Geography of Jinghang Grand Canal” by Shi Qing, which is the only work in the exhibition that was spontaneously created by the artist, not according to the given theme. The artist presents a unique journey in 2008 during which he travelled along Jinghang Grand Canal from Beijing to Hangzhou. Through performance, images and videos, Shi aims to discuss the energy issue along the canal. During the journey, he exchanged two tons of coal loaded in his van with petrol, food or edible oil step by step. He tried to turn this journey into a reflection on the geography of energy, through his unique barter and energy exchange.

“The Relevant Committee” is the youngest artist group that attends this Venice Biennale. This team of young artists with a strong tendency to intervene in society visited different sections of the Jinghang Grand Canal for this exhibition. The eight members of the group (which are Chen Zhiyuan, Gao Fei, Guo Lijun, Li Liangyong, Niu Ke, Wang Guilin and Ye Nan) collected various waste objects along the Grand Canal, and after disinfection wove them into a spiral rope that resembles a dragon, then inserted the images and videos taken along the canal into the rope. This rope, made of the fragments of life along the canal, became a report on the coexistence of the canal and its inhabitants in today’s life. The installation “Living Together” by The Irrelevant Committee was also a narrative map of the Grand Canal. It is what happened or is going to happen to the rope, but not its ultimate form, for no work could simply present the enormously changing reality once and for all.

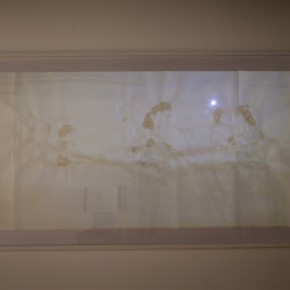

Beside “The Irrelevant Committee” is the video installation “The Grand Canal” created by Xu Bing specifically for this exhibition. He wrote three words “The Grand Canal” on a piece of rice paper with the water from the canal and left the writing drying and disappearing while the entire process was filmed. Audiences at the exhibition are presented with a delicately framed calligraphy work that is blank and crumpled due to the evaporation of the writing, but it only takes a few moments for this work to reveal its entire process, from being made to finally disappearing, which is due to the projector hidden opposite the work. The artist subtly and poetically connected time with the Grand Canal through a minimalist visual style; what once was there, will eventually be gone, leaving traces behind. As Xu Bing wrote, “Water flows through the crevices in the earth and the existence of life endures it. Ink streams through the cracks in the rice paper and the beauty of Chinese paintings reveal it. “Masters” in China are those who understand to treat nature with awe and respect. Complying with the divine, they always live in harmony with nature.”

Opposite Xu Bing’s work is “Running A Thousand Miles For An Appointment” by Bai Chongmin. Two treadmills are placed opposite each other in two semi-enclosed narrow boxes that are made from wooden boards. Audiences are invited to walk on the treadmills while watching the two videos. In this work, Bai Chongmin brought feathers as presents and travelled on foot from Beijing to other cities along the Grand Canal and arrived in Kunming to keep an appointment with his friend. He traversed plains and climbed mountains, travelling along the Grand Canal… The artist has documented the real social status quo in China through his photography and video journal. As a way of introspection looking inside, again he looked for the circumstances of self-generated culture on this land. Nowadays, modern efficient ways of communication inside have gradually submerged the multiple emotional experience of ancient people when they travelled a thousand li affected by the brilliant journey, poetic cadenza and friendly sentiments. In this unique way, Old Bai reflected the pale one-dimensional people living in industrialization, to once again experience and enjoy the quest for the poetic quality of humanity.

At the end of the exhibition room and below the end of “Canal Scroll” by Zhang Yanzi, hangs four pieces of paper work “Toxins” created by Xiao Lu. She dripped the toxins that had been expelled from her body through traditional Taosit massage, onto rice paper. The final images look elegant and beautiful, yet they emanate the smell of poison. She also placed a stone groove brought from China and water from the Venice canal in front of her work.

Apart from the works in the exhibition room, there is another one in the cloister downstairs. “L’amour Aux Temps De Chole?ra”, an installation and performance work by Wang Du, is one of the highlights in this exhibition. Through assistant curator Archibald Mckenzie’s communication and effort, the “boat”, which is made up of a bathtub, a bin and a diesel engine, was finally allowed to be placed in the reserve area of the cloister at Museo Diocesano Di Venezia. This work directly uses the name of the novel Love in the Time of Cholera (El amor en los tiempos del cólera, 1985) by Gabriel García Márquez to signify that fearlessness and romance are instincts of human survival, even when one has come to a situation of despair and total destruction. At the opening ceremony, Wang Du sat in the “boat” and started the engine. By improvisation he was able to hold Xiao Ge the curator aboard and asked her to open her arms at the bow of the boat, to imitate the famous Titanic pose, which got a thunder of applause. Audiences were also invited to join the performance.

The most unexpected work was, unsurprisingly, the performance by Xiao Lu, which was started right after the speeches given by the curator Xiao Ge, the commissioner Paolo De Grandis, director of Museo Diocesano Di Venezia Don Gianmatteo Caputo, the artist representative Guo Lijun, and assistant curator Archibald Mckenzie. Xiao Lu had planned to cover her entire body with the silt brought from the Grand Canal in China, then walk into the canal beside the museum and have a swim, to wash off the silt from China with the water in Venice. Unfortunately, the silt disappeared on the day before the opening. Since no other valuable equipment was lost, and the bucket of silt, properly labeled and stored, was too heavy to be easily taken outside the museum, it couldn’t be stolen or disposed of as waste. Therefore, Xiao Lu conjectured that the silt was hidden by the museum as they were worried that her performance would be too radical. The museum didn’t agree with Xiao Lu’s proposal for the performance, as they considered the silt would pollute the Venice canal. But Xiao Ge thought the opposite, since there was already silt in the Venice canal. At 4pm on the opening day, Xiao Lu was informed that she couldn’t conduct a nude performance even outside the museum gate and her initial plan had to be moved to somewhere else or simply cancelled, which made her very angry. Without having a discussion with the curator or the assistant curator, Xiao Lu discreetly walked to one of the entrances of the cloister in the museum and abruptly took off her clothes, then passed through the cloister garth that dates back to 12th century, rushed out of the museum, went into the canal outside, and started swimming. Meanwhile the scene was in turmoil and the director of the museum Don Gianmatteo Caputo was so infuriated that he shut the museum gate and began to hurl questions at Xiao Ge who didn’t know any better. Outside the museum gate, after swimming for a while, Xiao Lu was pulled out of water by two artist friends (Gao Jie and Yan Laichao). She quickly dried herself, and put on the coat offered by Archibald Mckenzie. Then she walked through St Mark’s Square and other streets in Venice bare foot, which took her 20 minutes to get to where she was staying.

Museo Diocesano Di Venezia is subordinated to the Patriarchal Curia of Venice and nudity is forbidden here. The staff in charge of the museum were irritated by the incident and the exhibition was temporarily closed at the opening ceremony. Through the communication and explanation by the curatorial team and people attending the event, finally, the museum expressed their lenience and understanding, but requested that Xiao Lu be forbidden from entering the museum again, and asked to clean the yard. This performance was also the first nude live performance conducted by Xiao Lu in her career and she named this sudden performance as “The Cleaning”. She is over 50 and her body is not in a great shape, which made this work even more real, more direct, and somewhat crude. It is, perhaps, within this context of collision and fusion of the traditional and the contemporary, that the Grand Canal is needed to help communication and break down all kinds of barriers.

Translated by Lv Meng/Image Courtesy The Grand Canal

Edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO